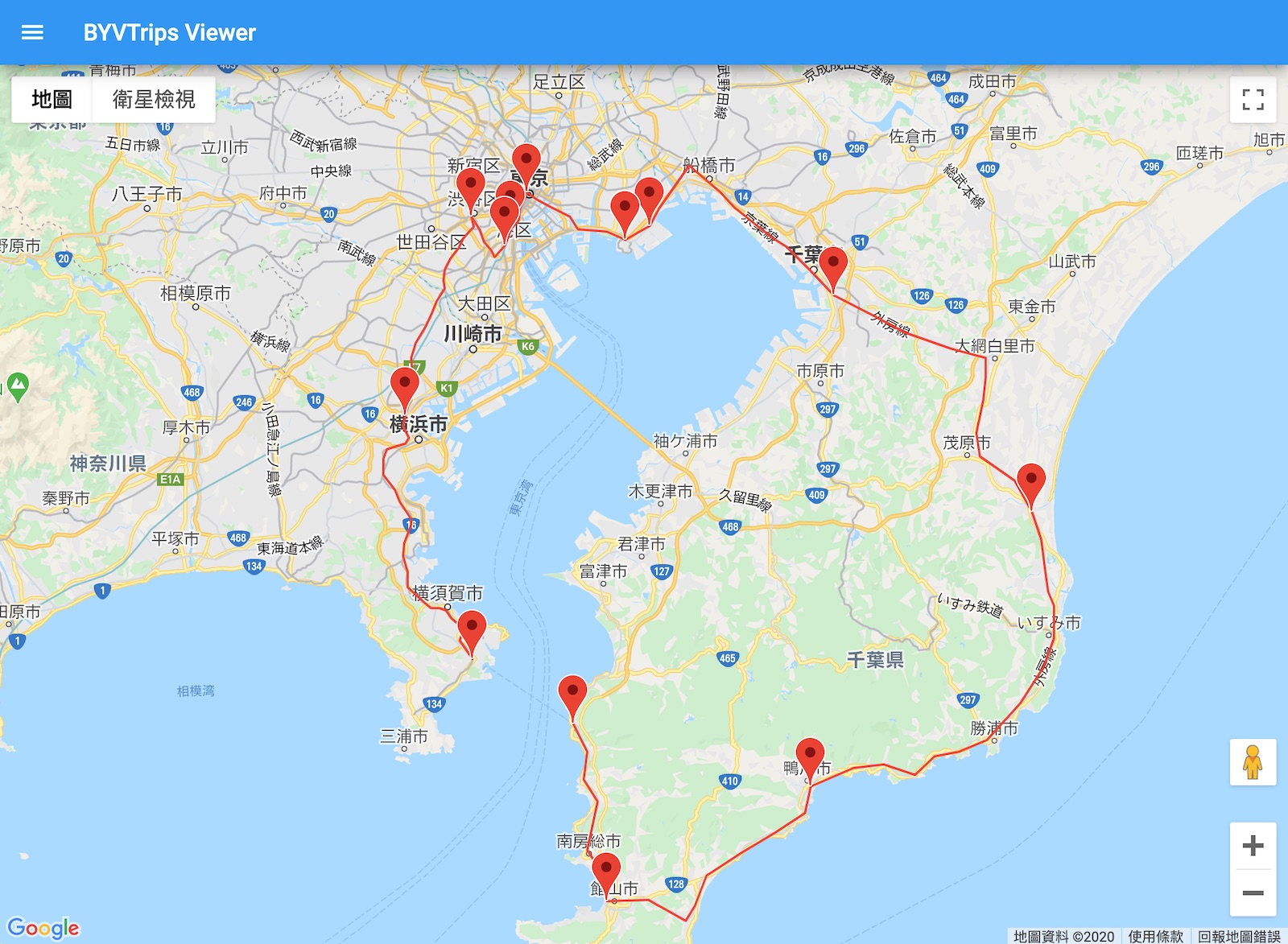

On March 14, 2020, just as Tokyo’s cherry blossom season was approaching, the temperature suddenly plummeted, and heavy rain began to fall. I had booked a weekend trip to Disney long ago, even using Hilton points to redeem a stay at the Hilton Tokyo Bay, but the park was closed due to the pandemic. Consequently, I changed my route to the Boso Peninsula, climbed Mount Nokogiri (Nokogiriyama), and finally took a ferry across Tokyo Bay.

Takanawa Gateway and the Closed Disney

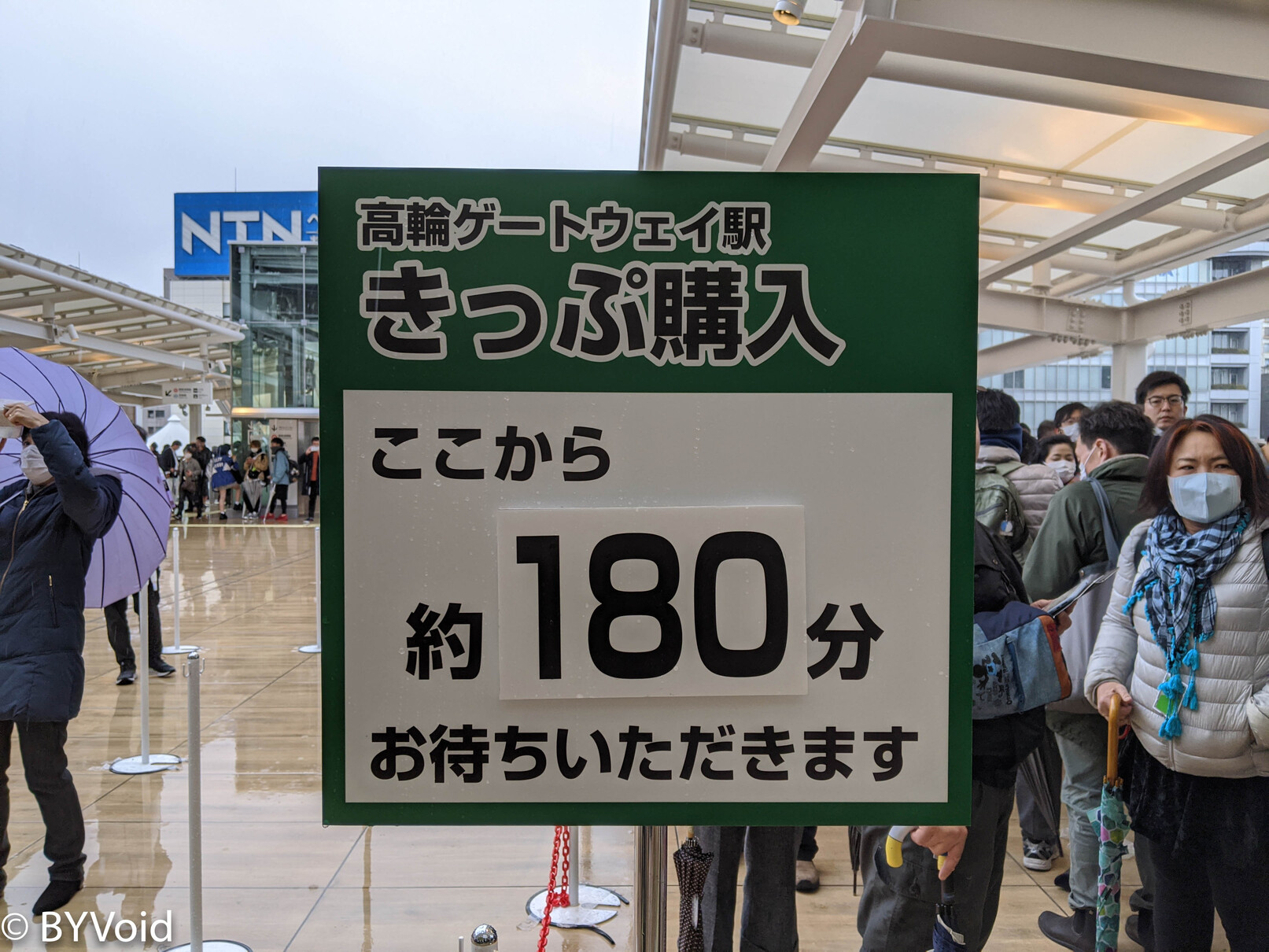

This was the opening day of the new station on Tokyo’s Yamanote Line, “Takanawa Gateway.” Although the opening ceremony was canceled due to pandemic concerns, quite a few people gathered at the station to take a look. I set off from Shibuya Station and used a “Reserved Seat Ticket Vending Machine” specifically to buy a physical one-way ticket as a souvenir. The station’s design is bright and airy, possessing a modern Japanese aesthetic.

In reality, there were fewer people inside the station than I had imagined, likely due to the severe weather and the unsettling nature of the virus. Although Japan had not yet declared a national state of emergency, the East Japan Railway Company (JR East) had already begun “self-restraint” (Jishu-kisei), canceling the originally planned opening ceremony. Outside the station, however, there were many people queuing to buy tickets. They probably all wanted to buy a ticket departing from the new station on its first day as a keepsake. I couldn’t understand why so many people were willing to queue for three hours in the rain just to buy a ticket printed with the station’s departure name on opening day. Is it not good enough to buy a one-way ticket to here from another station, like I did?

Speaking of the station’s name, which mixes Kana and Kanji, there is indeed some controversy. Japanese people are not used to such stations with mixed Kanji and Katakana names, especially on the Yamanote Line, which is almost the oldest railway in Japan. There are many reasons for the dislike; various negative reviews can be seen on Google Maps. The overly long station name causes inconvenience for printing and typesetting, and it feels out of place with other station names on the Yamanote Line. Although the Japanese public generally feels that English written in Katakana is very “oshare (fashionable),” it shouldn’t be used indiscriminately. In very traditional formal contexts, Kanji is still the standard.

Another unusual feature is the serif font on the entrance signboard, which is quite different from the style of other stations. In fact, not just stations, but Japanese signage generally uses sans-serif fonts. This design can only be described as unique.

Despite not being in the public’s comfort zone, the overall design of the Takanawa Gateway signboard is acceptable. Some people edited the image to mock the aesthetic level of Chinese railways.

The interior space design of Takanawa Gateway Station is excellent, and it has received generally positive reviews.

Leaving Takanawa Gateway, I went to Maihama on the Keiyo Line. I had booked a stay at the Hilton Tokyo Bay and originally wanted an immersive experience. Unfortunately, it coincided with the start of the Disney Resort closure, so my plan to visit Tokyo Disney for the first time in two years of living in Tokyo fell through. However, it was a good opportunity to see the deserted surroundings of Disney. After arriving at Maihama via the Keiyo Line, I transferred to the Disney Resort Line, which was indeed almost empty. Once on the train, I found a few people; I didn’t know if they were there specifically for sightseeing or if they didn’t know Disney was closed that day.

Although there weren’t many people in the hotel, there were two “Wedding Reception Banquets” being held. In the afternoon, the temperature actually dropped to freezing, and snowflakes began to fall. Such weather is extremely rare in Tokyo in mid-March.

Mount Nokogiri on the Boso Peninsula

Waking up early in the morning, the dark clouds had dispersed, sunlight poured into the room, and the seascape outside the window was exceptionally bright and beautiful.

Today’s plan was to travel around the Chiba Peninsula. The Chiba Peninsula is separated from Tokyo only by a strip of water, and there is a trans-oceanic bridge in the center. Having lived in Tokyo for two years, I had already visited all 47 prefectures, yet I surprisingly hadn’t been to Southern Chiba, which is close at hand. Although separated from the Greater Tokyo Area by only a body of water, the population density of Southern Chiba is quite low. Japan built the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line during the bubble era hoping for development on the opposite shore, but unfortunately, it had no effect, and the population of Southern Chiba continues to decrease. This phenomenon reminds me of Japan building the Shinkansen; the original expectation was that improving transportation with Tokyo would revitalize local economies, but in reality, it strengthened Tokyo’s siphoning effect on the regions.

The Chiba Peninsula is also called the Boso Peninsula (Bōsō-hantō), named after the two provinces under the Ritsuryo system: Awa (安房) and Kazusa (上總). Awa is the southern part of the peninsula, and Kazusa is the northern part.

The Japanese Kun’yomi reading of Awa Province (安房國) is exactly the same as Awa Province (阿波國) on Shikoku Island (Aha-no-kuni). According to the Heian period Shinto text Kogo Shūi, the Inbe clan from Awa Province (Shikoku) rode the Black Current to this place to expand the territory of “Togoku” (Eastern Country). Based on their homeland Awa, they named this place the homophonous “Aha” and chose the Kanji “安房” for their meaning to represent the reading; thus, Awa (安房) and Awa (阿波) sound the same. However, this is just one of the widely circulated theories. The system of reading place names for provinces established since the Nara period is very complicated because Japan had only recently introduced Kanji at that time, the rules were quite arbitrary, the Japanese phonology itself was different from later eras, and later generations often added far-fetched explanations, making research like looking at flowers in the fog.

My first destination was the Ichinomiya (First Shrine) of Kazusa Province, “Tamasaki Shrine.” Unlike the Kokubun-ji (Provincial Temples), the Ichinomiya was not designated by the central royal authority but was the shrine recognized within the province as having the most history and authority. An Ichinomiya is not necessarily large in scale; for example, this Tamasaki Shrine is not very big.

After a brief look at the Ichinomiya, I continued on the Sotobo Line train all the way to Awa-Kamogawa Station, where I transferred to the Uchibo Line. “Sotobo” (Outer Boso) and “Uchibo” (Inner Boso) refer to the outside and inside of the Boso Peninsula relative to Tokyo Bay, with the railway lines divided at Awa-Kamogawa. The train slowly arrived at Hama-Kanaya Station, where I got off for my next destination: Mount Nokogiri (Nokogiriyama). Hama-Kanaya Station is nestled against the mountains and faces the sea. Standing on the pedestrian bridge looking at the tracks, the scenery is very nice. This certainly doesn’t rank as Japan’s most beautiful station, but due to the clear weather, it was refreshing and gladdening to the heart.

Mount Nokogiri is famous for its Edo-period quarry and a famous temple on the mountain called “Kenkonzan Nihon-ji.” It is rare to use the country name “Nihon” (Japan) as a temple name, so it must have a significant background. Mount Nokogiri has a ropeway, and the entrance is about a 15-minute walk from the train station. Upon walking to the entrance, I discovered a long queue for the ropeway, far exceeding my expectations. Due to the large crowd, the operator ran the ropeway continuously instead of according to the timetable, so it was faster than imagined.

After taking the cable car up the mountain, an observation deck appeared before my eyes, offering a panoramic view of the Tokyo Bay seascape. Next to the observation deck, there is a small reference room exhibiting some historical materials about Mount Nokogiri.

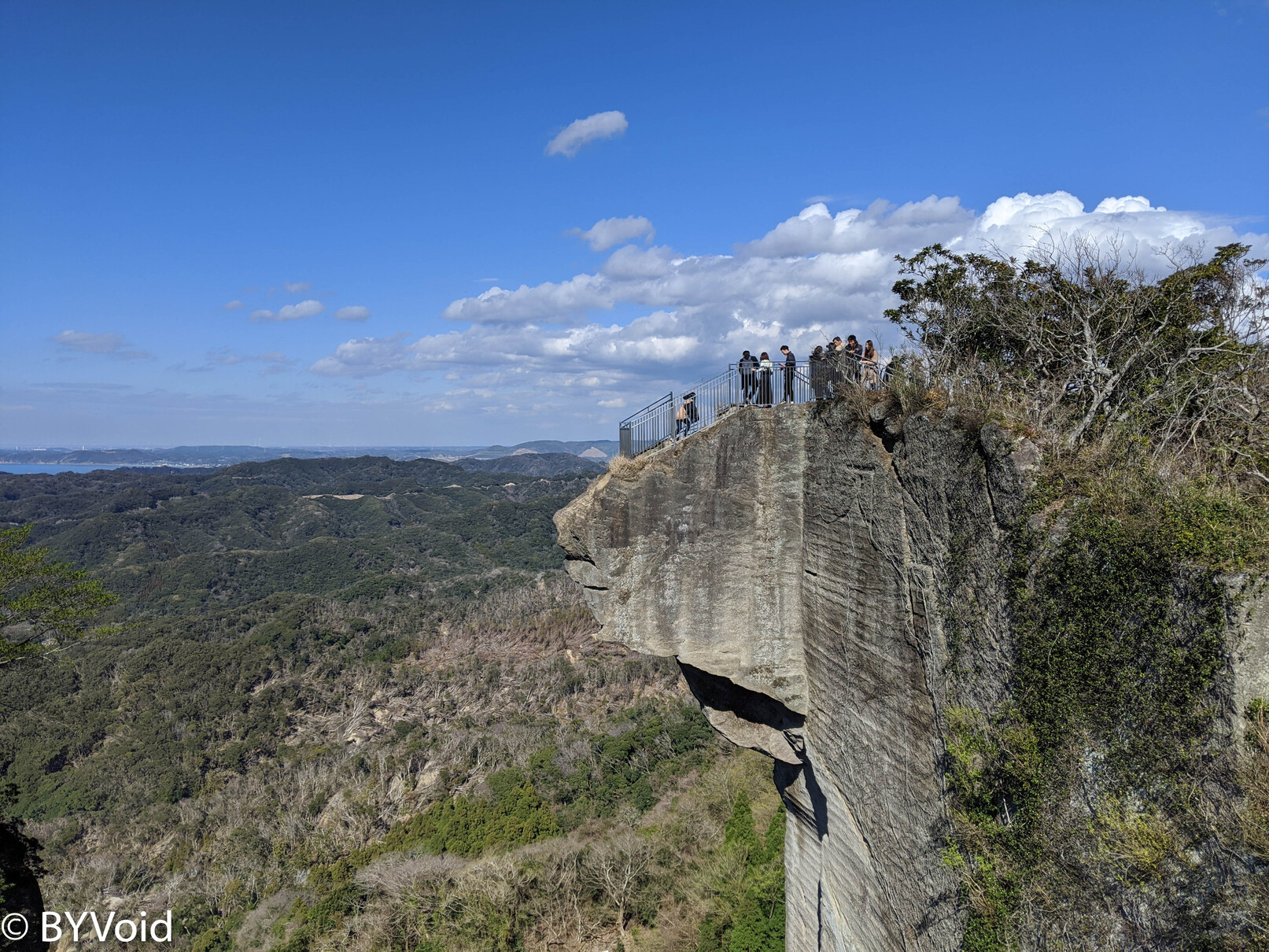

The observation deck is still some distance from the summit; it takes about twenty minutes to reach the top. The most famous feature of Mount Nokogiri is the quarry ruins (Ishikiriba-ato) on the mountain. Because the rock is tuff (solidified volcanic ash), which is very suitable as a building material, Daimyo began quarrying here from the Edo period. The quarry ruins look like saw teeth, hence the name Mount Nokogiri (Saw Mountain). Mount Nokogiri is located in Awa Province, so the stone produced here is also known as “Boshu Stone.” The large-scale quarries on the mountain were not decommissioned until the end of the Showa era. During that time, the quarried stone was widely used throughout Tokyo, such as in Waseda University, Yasukuni Shrine, and the Tokyo Bay Fortress.

Walking in the mountains, you can clearly see the traces of quarrying on the rock walls.

There are several protruding observation decks at the summit. From these decks, you can see the vertically cut rock walls. Extracting stone materials from such a height and transporting them down the mountain was truly a project of considerable scale.

Descending from the summit, there is another path leading to Nihon-ji. Nihon-ji was founded in the Nara period and has been a Buddhist sacred site in Awa Province for a thousand years. However, in 1939, most of the buildings were destroyed in a fire, which was not unrelated to the “Haibutsu Kishaku” (anti-Buddhist) movement at the time. In the center of the temple is a stone Great Buddha carved in 1783. The Great Buddha was restored a few decades ago and now looks very well maintained.

Near the Great Buddha, there is also a “Holy Bodhi Tree” planted in 1989, which has now been transplanted to the study hall. This tree was specially transplanted by the Indian government from Bodh Gaya, the place of the Buddha’s great enlightenment. Next to it stands a “Four-Lion Pillar of the First Sermon” (Ashoka Pillar) to symbolize Japan-India friendship.

After seeing Nihon-ji, one has to return to the summit via the original route to descend the mountain. Before descending, I saw that the crowd at the rock wall observation deck had not decreased but had formed an even longer line.

I hiked down the back of the mountain, taking about 40 minutes to reach the harbor side. For the return trip, I chose to take a ferry across Tokyo Bay to enjoy the sea scenery.

About half an hour later, the ship arrived at Kurihama in Yokosuka on the opposite shore. By this time, the setting sun had begun to sink slowly in the west. I boarded the Keikyu train and returned to Tokyo, bringing the day’s trip to an end.

Last modified on 2020-07-15