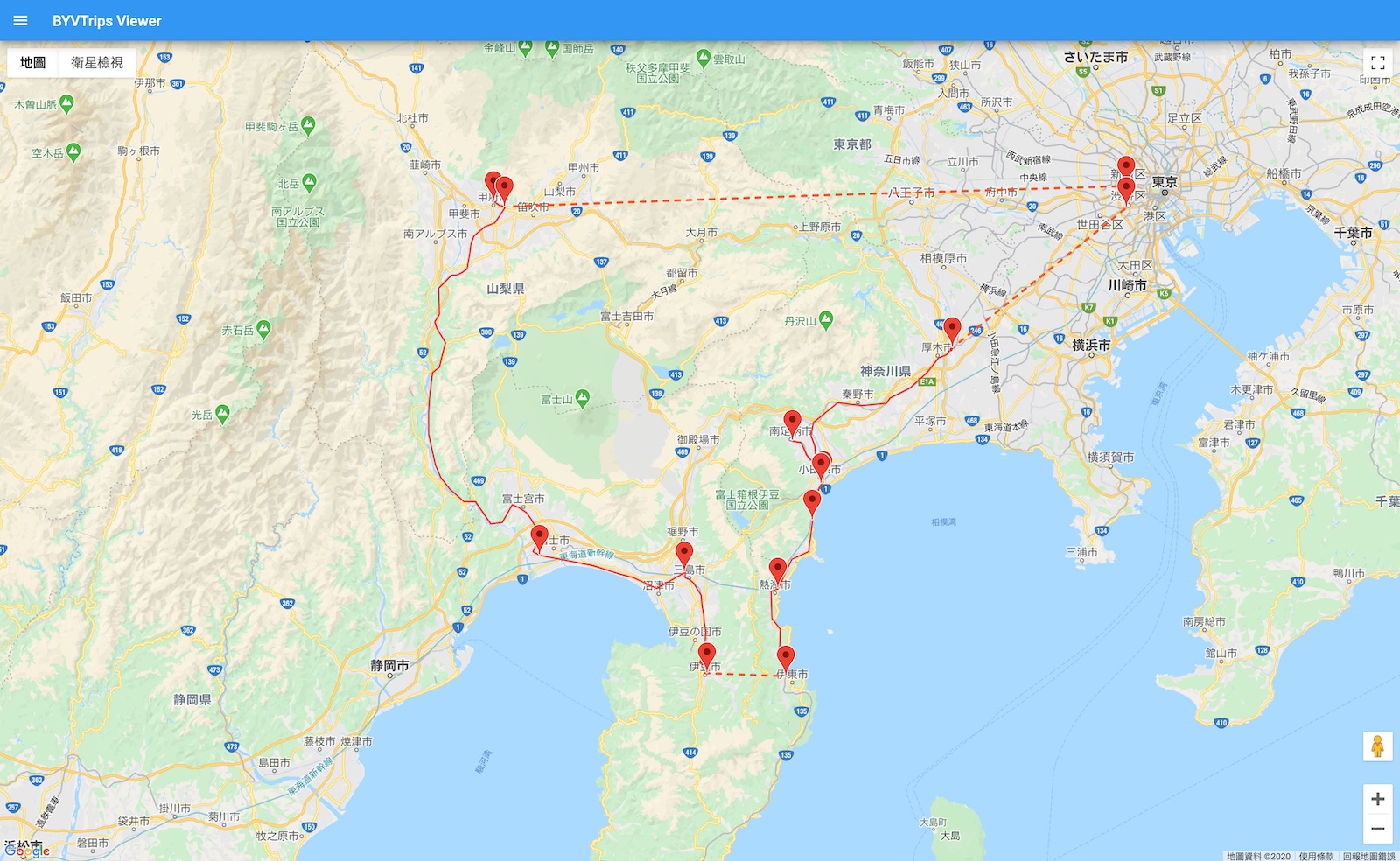

Time rewinds to March 2020, right before the nationwide “State of Emergency” was declared in Japan, coinciding with the cherry blossom season. I spent a weekend touring Kofu, followed by Shuzenji, Ito, and Atami on the Izu Peninsula.

By this time, the number of tourists across Japan had already started to dwindle, especially those from China. However, some European and American tourists could still be seen, foreshadowing the virus outbreak that would come in April.

Day 1: From Zenko-ji to Shuzen-ji

Before the Vernal Equinox, to make full use of the daylight, I got up before six in the morning. I took the Yamanote Line to Shinjuku and boarded the Keio Highway Bus I had reserved online. The bus departed at 7:00 AM, heading straight for Kofu. The fare was only 2,000 yen, compared to the expensive Chuo Line Limited Express train ticket which costs nearly 4,000 yen. The Shinjuku Expressway Bus Terminal was clean, tidy, and orderly—even better than I had expected.

I slept for two hours on the bus. I only vaguely recall that many stops along the way were on the highway, where pedestrians could walk down directly from the elevated road. I opened my eyes just as we arrived at Zenko-ji and immediately jumped off.

The full name of this temple is Kai Zenko-ji, as there are several Zenko-ji temples in various places. These temples are not simply related as head and branch temples but have a more complex history. The name Zenko-ji dates back to the Hakuchi era of the Asuka period, shortly after the Taika Reform when Japan was introducing Buddhism on a large scale. Zenko-ji was originally built in Shinano Province (modern-day Nagano), and its most famous feature was the “Absolute Secret Buddha” (Zettai Hibutsu) presented by King Seong of Baekje. In the Nara period, Shinano was considered a remote region, so having such a famous temple there was no small feat; consequently, it attracted war and covetous factions. During the Warring States period, the daimyo Takeda Shingen, wishing to prevent the flames of war from reaching Shinano Zenko-ji, transferred its principal image—the “Baekje Absolute Secret Buddha”—to his territory in Kofu, erecting another Zenko-ji there.

Opinions vary on where the “Absolute Secret Buddha” went afterward. Although it is generally believed to have returned to the original Shinano Zenko-ji (in Nagano), because it is absolutely secret and cannot be publicly displayed, no one has seen it for hundreds of years. According to records, apart from a public display in the 5th year of Hakuchi (654 AD), no one has seen it since. The “Gokaicho” (unveiling) that happens once every seven years displays only a stand-in replica that has been copied repeatedly over the years. This hides a fundamental philosophical question: Can an object that cannot be observed be said to exist? Since no one has truly observed it for so long, we might as well call it “Schrödinger’s Buddha”.

Unlike the incense-filled Shinano Zenko-ji, Kai Zenko-ji was cold and deserted. The main gate (Sanmon) and the main hall (Kondo) even had a sense of dilapidation from years of disrepair, paling in comparison to Japanese ancient temples that are often restored to look like new. It actually resembled some old architecture found in North Korea or China twenty years ago.

After seeing Zenko-ji, I originally planned to take a bus to Takeda Shrine, but when I walked to the bus stop, I found a notice announcing a temporary cancellation. The reason was that the Yamanashi Prefectural Science Center was temporarily closed to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, so the bus line was suspended as well. Perhaps most people who usually take this line go to the Science Center.

I had to change my plans on the fly and walked forty minutes to Kofu City Castle Park. Kofu gets its name from Kai Province (Historical Kana Orthography: かひのくに - Kahi no Kuni), named Kofu because it was the location of the provincial capital (Kokufu). The existing Kofu Castle was built on the orders of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and was not abolished until after the Meiji Restoration. Now, there are some reconstructed gates at the base of Kofu Castle, and the stone foundation of the keep (Tenshudai) remains at the top. The view from the Tenshudai is quite nice.

Considering that getting to Takeda Shrine was inconvenient, I decided to leave Kofu after seeing the castle. I took the JR Central Minobu Line Limited Express “Wide View Fujikawa” to Fuji Station, then transferred to the Tokaido Main Line to Mishima, and finally switched to the Izu Hakone Railway Sunzu Line to reach Shuzenji. I expected to use my IC transport card, so I only bought the non-reserved seat limited express ticket from Kofu to Fuji. In Japan, train tickets are sold separately as a base fare ticket and an express ticket (tokkyuken), which is uncommon in other countries. The advantage is that you can buy segments as needed. However, when I tapped my card to enter the station and walked to the platform, I discovered that the Minobu Line does not accept IC cards. There were no staff members around, so I just boarded the train. This situation happens occasionally, usually when crossing between different railway company zones or transferring from a main line directly to a low-volume branch line. To cut costs, low-volume branch lines generally don’t have machines at entrances/exits to read IC cards, and some don’t even have ticket gates, requiring manual ticket checks on the train.

After waiting a while, I finally encountered a conductor checking tickets. I explained in my unskilled Japanese that I used an IC card to enter. The conductor prepared to charge me the fare and then clear my entry record on the card. However, his handheld device couldn’t read the Mobile Suica on my phone, so he eventually wrote me a paper slip and told me to pay at the destination station.

Although there were no obstacles exiting the station in the end, it would be very troublesome if one didn’t speak any Japanese, for instance, foreign tourists. The fact that most tourism and transport operators do not speak the international common language (English) has always been a major barrier for Japan in attracting foreigners. Even in 2020, when they were supposed to welcome a large number of foreign tourists for the Olympics, this hadn’t been resolved. One of the most exaggerated news stories was from early 2017: A ticket seller at Shinjuku Gyoen let 160,000 foreign tourists enter for free over more than two years because he was afraid to speak to foreigners, causing a loss of tens of millions of yen in ticket revenue for the park (Source).

After multiple transfers, I finally arrived at my destination, Shuzenji. There is still some distance between Shuzenji Station and the Shuzenji Onsen area. Since I had to take a bus anyway, I went directly to a theme park called “Niji-no-Sato” (Rainbow Village). The admission fee was 1,220 yen. It covers a large area, divided into a British Village, a Canadian Village, and a Japanese Village, connected by a miniature train. Each section features buildings in the local style, accompanied by music and shops, creating an immersive experience. The buildings in the British Village are all Tudor style, giving the feeling of an English town. I strolled around for over an hour until it closed at 4:00 PM.

Parks of this style can be said to be a characteristic of Japan, focusing on cultural sightseeing without many thrilling rides. Among this type of park, my favorite so far is Meiji-Mura near Nagoya.

After coming out, I continued walking along the road to “Shuzenji Plum Grove”. I thought I might see plum blossoms in this season, but most of the trees were actually bare. Passing through the plum grove, I came to a path through a cedar forest and walked down the mountain to Shuzen-ji (the temple).

Shuzen-ji is now a Soto Zen temple. It is said to have been founded by Kobo Daishi (Kukai) and originally belonged to the Shingon sect. In the Kamakura period, it was named “Shuzen-ji” (written as 修善寺 - Temple of Cultivating Goodness). Later, the temple converted to the Zen sect, so the name was changed to “Shuzen-ji” (written as 修禪寺 - Temple of Cultivating Zen). Although the temple is called “Shuzen-ji” (with Zen), the place name remains Shuzenji (with Goodness) Onsen. In Japanese, “Shuzen-ji” (修禪寺) and “Shuzenji” (修善寺) are homophones, both pronounced shuzenji. Japanese Kanji do not have tones, and the voiced initials of the Go-on readings are preserved. In Mandarin Chinese, however, words with the historical initial j- (represented here by ‘Zhan’/‘Shan’) evolved differently: the level tone became the affricate ch (chán), and the oblique tone became the fricative sh (shàn). The character “禪” (Zen) is pronounced chán in the level tone (e.g., 禪宗 - Zen Buddhism) and shàn in the oblique tone (e.g., 禪讓 - abdication).

There were quite a few tourists at Shuzen-ji because the cherry blossoms inside the temple were in full bloom, creating beautiful scenery.

Leaving the temple, I visited the nearby Hie Shrine and Shigetsuden on the other side of the Katsura River. Shigetsuden commemorates Minamoto no Yoriie, the second shogun of the Kamakura shogunate who was assassinated. I then walked to the Kaede Bridge and Katsura Bridge over the river, passing through a bamboo grove path in between—the scenery was quiet and secluded. Finally, I soaked my feet in the open-air footbath by the river, a hot spring legendarily created by Kobo Daishi’s divine power.

After dinner, I went for a bath at a small public hot spring called “Hakoyu” by the river. Hakoyu claims a history of several hundred years, and the building is made entirely of wood, including the floor inside the bath area and the bathtub itself. The bathing fee is only 350 yen, which is truly very cheap.

Day 2: Tokai, Anjin, and the Art Museum

When I woke up in the morning, it had started to rain outside. Checking the weather forecast, I saw it would rain all day, just like the rainy season. Before leaving Shuzenji, I went to the Kaede Bridge and the bamboo grove path again. The bamboo grove and the stream in the rain were even more secluded and serene.

I took a bus from Shuzenji Onsen to Shuzenji Station, transferred, and took another hour-long bus ride to Ito City on the other side of the peninsula. Crossing the mountains, mist drifted through the forest in the rain, making it appear even more mysterious.

I had been to Ito twice before, but neither time did I visit the famous “Tokaikan”. Tokaikan is a traditional Japanese wooden building, three stories high, topped with a tower, built at the end of the Taisho era. It operated as a ryokan (hot spring inn) from the 3rd year of Showa until 1997. Now, Tokaikan has been opened to the public as a museum. The ticket is only 200 yen, allowing visitors to view every guest room and the grand hall of the past. The room decorations are elegant and exquisite, with many historical materials on display. There is a hot spring on the first floor, but I arrived too early and it hadn’t opened yet, so I gave up on the experience.

One room in Tokaikan displays the story of the legendary figure Miura Anjin. Miura Anjin was an English sailor originally named William Adams. In 1598, he joined the Dutch East India Company and headed to the Far East for the spice trade. However, due to shipwrecks, only one of the original five ships remained, drifting ashore at Usuki in Kyushu nineteen months later. Upon landing, they were immediately captured by the local daimyo and accused of being pirates by Jesuit missionaries. Fortunately, Adams met Tokugawa Ieyasu and explained the reason for their voyage and the persecution of Protestants by the Jesuits, successfully gaining Ieyasu’s trust. Later, he was taken to Edo and helped the Tokugawa shogunate build Japan’s first Western-style shipyard in Ito. He even went to the Philippines as a representative of Japan to establish trade relations with New Spain. In the end, Tokugawa Ieyasu made Adams a samurai with a fief in Miura District and bestowed upon him the name Anjin (“Pilot”). Under Miura Anjin’s influence, Tokugawa Ieyasu expelled the Jesuits from Japan and banned Catholicism. The British East India Company established a trading post in Hirado in 1613; its main purpose was actually to trade with China, and Miura Anjin participated in this. He was eventually buried in Hirado. Today, there are memorials to Miura Anjin in several places in Japan. Ito even holds an “Anjin Festival” every year, and there is an “Anjin-dori” (Anjin Street) near Nihonbashi in Tokyo. During the Age of Discovery, quite a few Westerners visited Japan, and many left significant marks, which may be one reason why Japan’s opening to the world later was much smoother than that of the Qing Dynasty. Under the Chinese historical perspective, commemorating these foreigners like this would be unimaginable—just look at the St. Francis Xavier monuments in Kagoshima and Shangchuan Island to understand.

After visiting Tokaikan, I took a train from Ito Station to Atami. I had been to Atami more than four times, but mostly for hot springs and scenery. This time I was going to the MOA Museum of Art, which I had missed before. The MOA Museum was completed in 1982 and was originally named the “Mokichi Okada Association Museum of Art” (or Kyusei Atami Art Museum). The name clearly has a unique origin; the founder, Mokichi Okada, was the leader of the new religion “Sekai Kyusei Kyo” (Church of World Messianity). Like all cult leaders, Okada was very wealthy, but he was also an art lover and collector. He founded two museums in the name of the church: one is the Hakone Museum of Art, and the other is this MOA Museum of Art. MOA stands for Mokichi Okada Association.

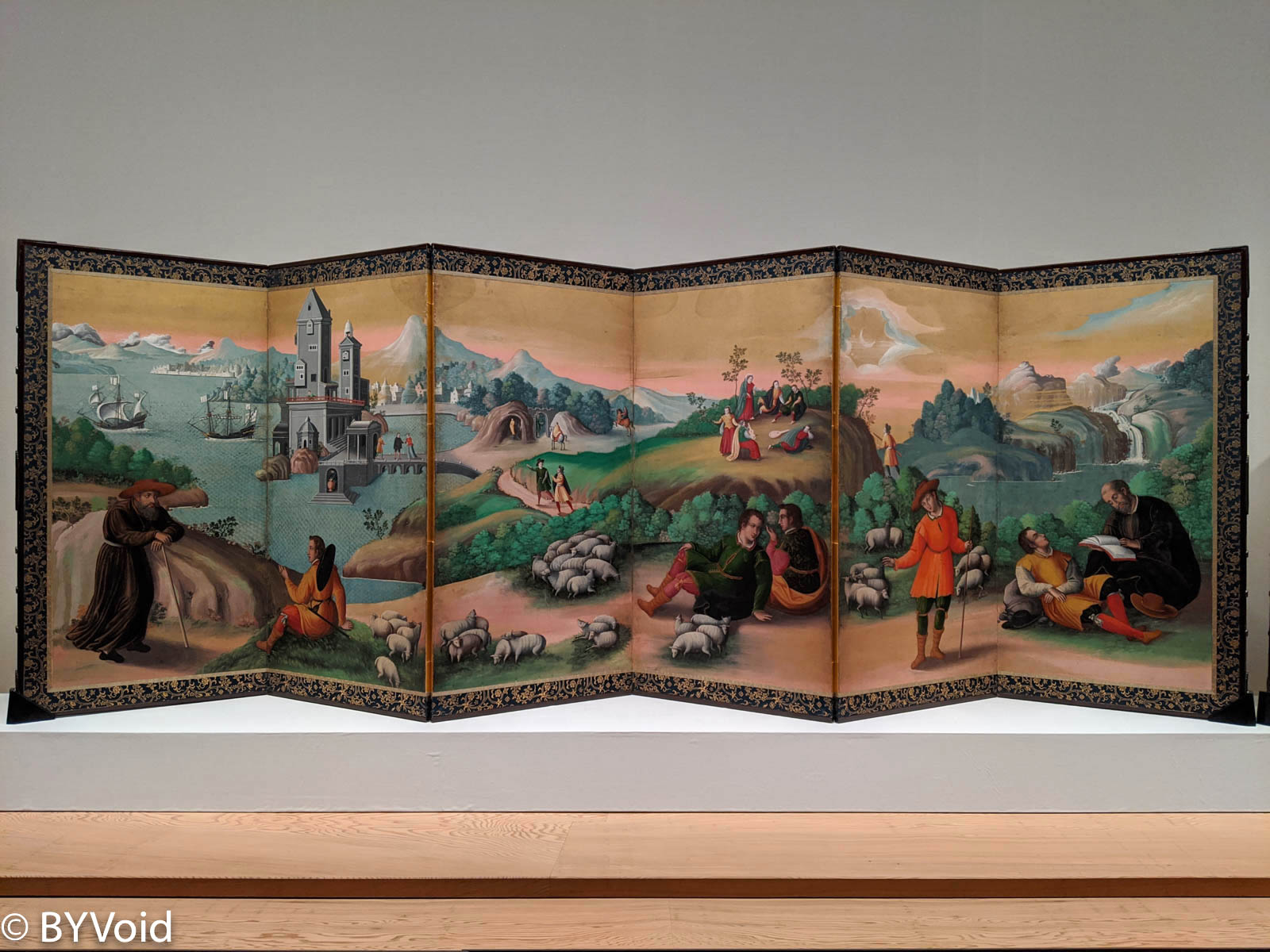

The museum is built halfway up a mountain west of Atami. From the lower entrance, one must pass through multiple escalators to reach the museum lobby. Each section of the escalator has a special lighting design. The upper lobby is very artistic, offering a view of the mountain scenery through huge floor-to-ceiling windows. That day, the mist was swirling, making it feel like being in the heavens. The museum is not large, with only six exhibition halls, but each hall contains masterpieces. Among them, I found the “Screen of Westerners Playing Music” most interesting. This is a sixteenth-century oil painting by a Japanese artist who studied Western painting under Jesuit missionaries. The painting depicts Westerners playing music in a harbor and on hills.

Outside the museum, there is an attached Japanese garden. The moss-covered paths looked exceptionally graceful in the rain.

It was getting late, so I enjoyed lunch at a restaurant in the garden.

Leaving Atami in the afternoon, I originally planned to go to Daiyuzan near Odawara, where there is a Soto Zen temple on the mountain. After taking the Izu Hakone Railway to Daiyuzan Station, I found the rain was too heavy, so I had to give up. I returned to Odawara and took a train to Nebukawa Station to go to the Hilton Resort. This was my second time here; the last time was about a year ago. It is a luxury resort built during the late bubble economy era in Japan, originally named “Spausa Odawara”. When completed in 1997, the construction cost was as high as 44.5 billion yen. Later, as the Japanese economy declined, it ended up like many sky-high priced properties of that time—sold cheaply to the American Hilton Group.

My favorite place here is the twelve-story building built on the hill. All rooms have balconies facing east, offering unparalleled sea views. At the same time, as a member of the Hilton Group, the resort’s management style aligns with international standards and is not overly Japanese. There were quite a few people in the lobby, but to prevent the novel coronavirus, the buffet and Diamond Member Lounge were closed, and breakfast was changed to a set meal. Even so, I spent a wonderful afternoon here.

Day 3: Sagami Kokubun-ji

The window faced directly east towards the sea, and the sunlight at 6:00 AM was already dazzling. After a day of gloom and rain, this day was exceptionally clear, with temperatures rising to twenty degrees in the morning. On the Odakyu train back to Tokyo, I could clearly see Mount Fuji covered in white snow in the distance.

For the return trip, I chose to transfer at Ebina, mainly to experience the Sotetsu Direct Line that started operating at the end of last November. The direct train runs from Ebina all the way to Shinjuku, passing through a newly constructed section before connecting to the JR East Yokosuka Line.

While transferring at Ebina, I took a walk to the nearby Sagami Kokubun-ji ruins. After the Taika Reform in the Asuka period, the Yamato court tried to imitate the centralized power of the Tang Dynasty and established “Provinces” (Ritsuryo states) throughout Japan. Each province had a corresponding Kokubun-ji (Provincial Temple) to propagate Buddhism. The area near Ebina was the location of the provincial capital (Kokufu) of Sagami Province, and the Kokubun-ji was built on a high platform. It takes about 10 minutes to walk from the train station, and there is a reconstructed seven-story pagoda of the Kokubun-ji in the station square. Only the foundation stones of the buildings remain at the Kokubun-ji ruins now, but one can discern the “Garan” layout where the pagoda and the Golden Hall stood side by side in the Heian period, remarkably similar to Horyu-ji in Nara.

After seeing the Kokubun-ji ruins and returning to Ebina, I caught the Sotetsu Direct train just in time. Sitting on the train, passing through the new Hazawa yokohama-kokudai Station, the route was underground all the way until it connected to the Yokosuka Line and the Saikyo Line.

Summary

This trip was only two days long, but the content was substantial. I experienced both Japan’s history and modernity, and the biggest gain was learning about the deeds of Miura Anjin.

Last modified on 2020-06-11