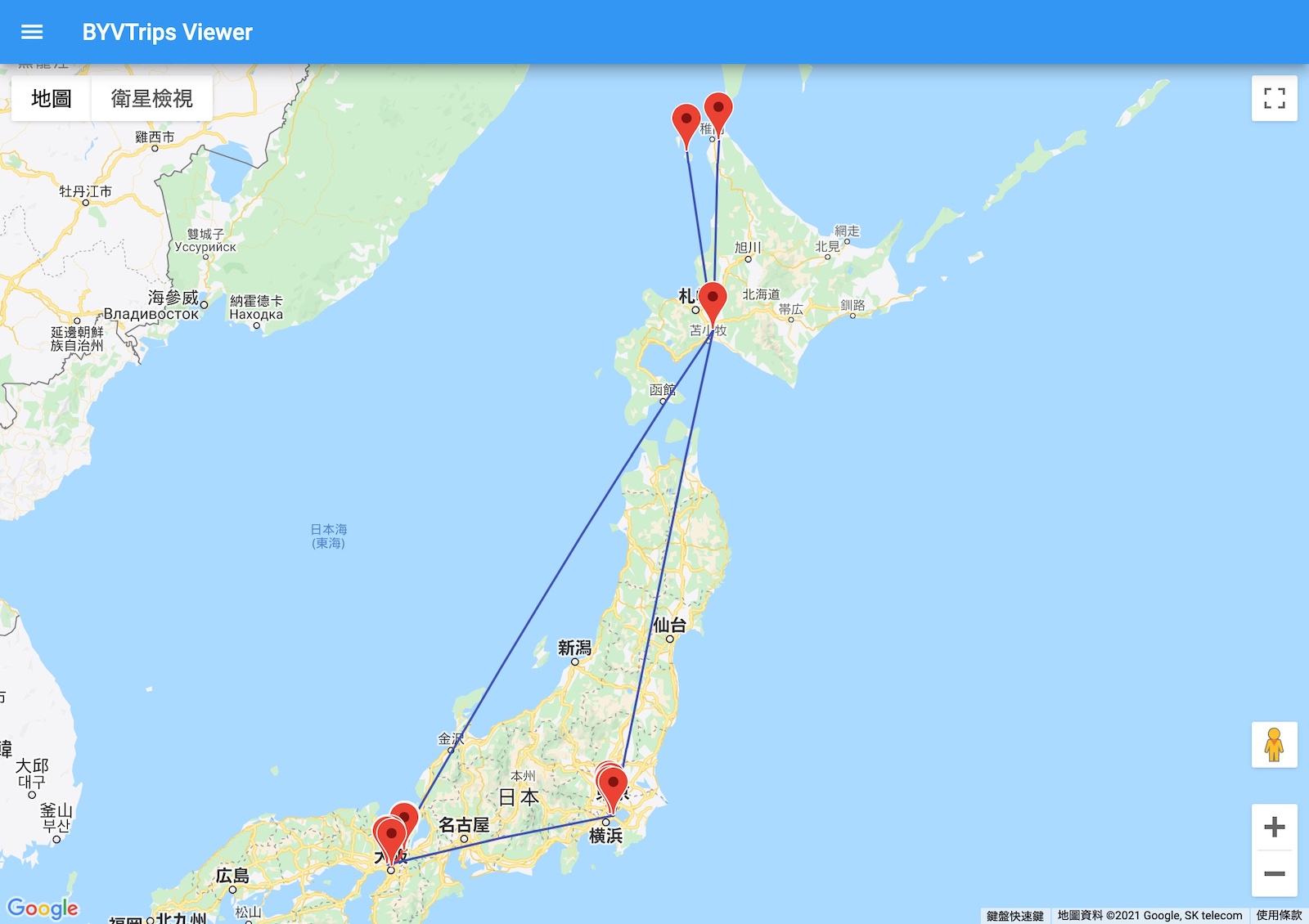

Since late March 2020, I had been practicing “Jishuku” (self-restraint) at home. After staying dormant for several months, early July 2020 arrived in the blink of an eye, and I embarked on a new journey. I spent a total of five days visiting Wakkanai (稚內), the northernmost point of Japan, and two nearby remote islands: Rebun (禮文) and Rishiri (利尻). Afterward, I visited Lake Shikotsu (支笏湖) and Lake Toya (洞爺湖) near Sapporo (札幌), and finally stopped by Kyoto (京都).

The itinerary involved two flight tickets: Tokyo Haneda-Sapporo-Wakkanai, and Rishiri-Sapporo-Osaka-Tokyo. Both were All Nippon Airways (ANA) tickets redeemed using United Airlines mileage. Each ticket cost only 5,000 miles with zero taxes and fees. If purchased directly from ANA, the price would likely have exceeded 50,000 yen. Domestic flights in Japan might be the most cost-effective way to redeem United Airlines miles.

New Chitose Airport

Since the flight was scheduled for 7:00 AM, I woke up shortly after 5:00 AM and took the airport bus from Shibuya directly to Haneda. Because the traffic volume was far less than before, I arrived at Haneda Airport in less than thirty minutes. Like my previous trip to Wajima, Haneda Airport remained somewhat deserted; even though it was already July, nearly half of the flights were still canceled.

The plane took off on time. The number of passengers onboard was not insignificant; about 70% of the seats were occupied. Although the number of infections had dropped at one point, the pandemic was far from over. However, the tourism industry had passed its darkest days, even though the Japanese government’s “Go To Travel” subsidy campaign hadn’t started yet. In my opinion, locking down cities worldwide is not a long-term solution for pandemic prevention; the ultimate outcome can only be successfully achieving coexistence with the virus. Before reaching this outcome, some deaths are inevitable, but humanity will be better prepared for such disasters in the future. After all, the disasters potentially triggered by future climate change will likely be far greater than this, so we might as well treat this pandemic as a drill.

Over an hour later, the plane landed at New Chitose Airport (新千歲機場) in Sapporo. There were very few travelers inside the airport, and many shops hadn’t opened yet. I managed to find an open restaurant to eat breakfast, and just as I was preparing to board, I discovered that the flight to Wakkanai had been delayed until noon. Suddenly having several extra hours, I took the opportunity to explore the airport thoroughly. New Chitose Airport has excellent facilities and diverse functions. In addition to various food and souvenir shops, there is also a cinema and an open-air hot spring (onsen). In terms of airport facilities, Japan and Western European countries are the richest; they can even attract people to visit specifically without flying. Airports in the United States and China appear slightly dull and singular by comparison; one generally wouldn’t go there without a reason. There is an area on the third floor of the airport that introduces the history of New Chitose Airport, starting from the pre-WWII Chitose Airfield up to the current “New” Chitose Airport.

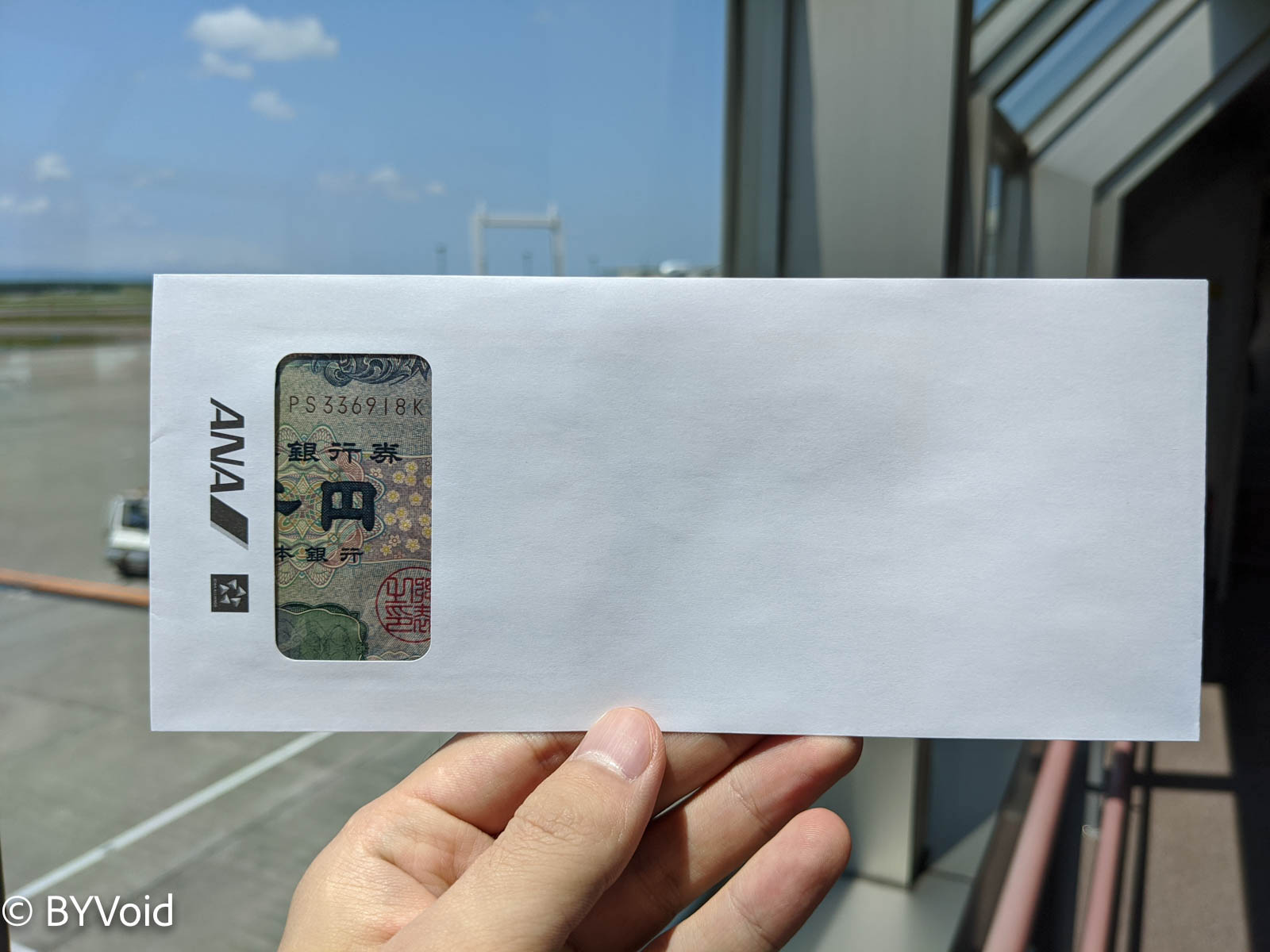

After a delay of an hour and a half, boarding finally began. During this time, everyone waited quietly. Although the hour-and-a-half delay was announced early on, airport staff made announcements every twenty minutes or so to explain the specific situation, including the reason for the delay, the current location of the replacement aircraft, and when it would arrive. It was evident that under the premise of transparent information, passenger tolerance significantly improved—this wasn’t just due to the high civility of the Japanese people, but more importantly, timely communication. What surprised and touched me the most was that upon boarding, ANA compensated every passenger with 1,000 yen in cash, placed in an envelope. Upon opening the envelope, any remaining dissatisfaction I had instantly dissolved. ANA’s good service is indeed reflected in the details, treating every traveler as a long-term customer to cultivate. At the same time, the operating costs of Japan’s two major airlines (ANA and Japan Airlines) have remained high, with cost per passenger-mile ranking among the highest in the world, which is out of step with the global trend of low-cost competition among airlines. I wonder if ANA can sustain this business strategy of high prices and high standards.

Cape Soya and Sarobetsu

After arriving at Wakkanai Airport, it was already past noon. The airport now only has two flights a day, so the staff basically only work during these times. After collecting my luggage, the staff from Nippon Rent-A-Car were already waiting at the exit.

After picking up the car, I immediately headed to Cape Soya (宗谷岬), the northernmost point of Japan. I had been here once three years ago during my first trip to Hokkaido. Back then, I joined a half-day sightseeing tour booked in Wakkanai. Seeing it again this time, it felt even more deserted. However, the weather was exceptionally good that afternoon, with visibility of several tens of kilometers. Standing at Cape Soya, I could see Sakhalin (Karafuto/樺太) across the strait. However, some might disagree with the claim that Cape Soya is Japan’s northernmost point because the northern tip of Iturup (Etorofu/擇捉島), one of the Northern Territories claimed by Japan, is at a higher latitude, though it is currently under actual Russian occupation.

Continuing south along the Sea of Okhotsk, I passed a place called Sarufutsu Village (猿拂村). By the sea, there is a stone monument commemorating the landing point of the former undersea cable connecting Hokkaido and Karafuto. The text on the monument commemorates the “Nine Maidens” (九人乙女), and reading between the lines reveals the pain of losing one’s country and home. according to the explanatory text, the “Nine Maidens” were nine women who “committed suicide for their country” at the post office in Maoka (Holmsk) on Karafuto on August 20, 1945. This was already several days after Japan had announced its surrender, but the Soviet offensive remained brutal, so they became the final sacrifice of militarism. Today, the memorial tablets of these nine women are in the Yasukuni Shrine (靖國神社) in Tokyo. On the surface, it is out of reverence for them, but underneath, it perhaps reflects resentment over the Empire of Japan’s loss of Karafuto.

Turning inland from the seaside, I spent over an hour driving through a dense forest to reach the Sea of Japan side. Near the coast is an open wetland named the Sarobetsu Wetland (佐呂別溼原). The Sarobetsu Wetland covers an area of 200 square kilometers, and most of it is primitive wetland. This area was originally targeted for land reclamation after WWII, but after 1965 it was designated as a national park, allowing its original state to be preserved.

Standing by the road looking towards the wetland, a cool north wind blew. Flowers dotted the grass, which was as tall as a person, backed by the setting sun and volcanic cones.

The glory before the sunset is fleeting, so I continued westward. By the time I reached the shore of the Sea of Japan, the sun had begun to sink in the west. Behind the vast wetland stood Mt. Rishiri Fuji (利尻富士) across the sea; the scenery was magnificent.

I stood by the sea until the sun had completely fallen into the ocean before leaving. Such beautiful scenery is unforgettable for a lifetime.

Wakkanai and the Other Side of the Sea

The next day, I woke up early to find the sky didn’t look good; Rishiri Fuji on the sea had completely disappeared from sight. Not only that, but a gale was blowing, and the temperature had plummeted to only 15 degrees Celsius. In fact, this is the typical summer weather in Wakkanai; the clear skies of the previous day were the rarity. Wakkanai, Rebun, and Rishiri are located exactly at the confluence of the Tsushima Current (warm) from the Sea of Japan and the Liman Current (cold) from the west of Sakhalin, making the climate here changeable and especially foggy in summer.

After breakfast, following a brief stop at Cape Noshappu, I headed to Wakkanai Park. Wakkanai Park is on a hill, and at the summit is the Centennial Memorial Tower. The observation deck on the top floor offers views in all directions. If the weather is good, you can simultaneously see Karafuto to the north, Rebun and Rishiri to the west, and Cape Soya to the east. Unfortunately, I could only see Wakkanai City below; Rishiri Island and Sakhalin, which were clearly visible yesterday, were gone. However, compared to the thick fog when I first came here in 2017, it was already much better.

The bottom two floors of the Centennial Memorial Tower house a museum. The first floor introduces local Wakkanai folklore and the surveying and exploration of Ino Tadataka (伊能忠敬) and Mamiya Rinzo (間宮林藏). On the floor is a large map of Hokkaido drawn by Ino Tadataka in the early 19th century; the technique is superb. Mamiya Rinzo’s two expeditions to Karafuto departed from Wakkanai. An interesting detail is that Mamiya Rinzo’s fleet found the mouth of the Amur River (Black Dragon River/黑龍江) and even met with local officials of the Qing Dynasty near Mykolayivsk-on-Amur. Mamiya Rinzo’s book “Todatsu Chiho Kiko” (Travels in East Tartary) contains illustrations of “Barbarian Disturbances,” depicting very vivid scenes.

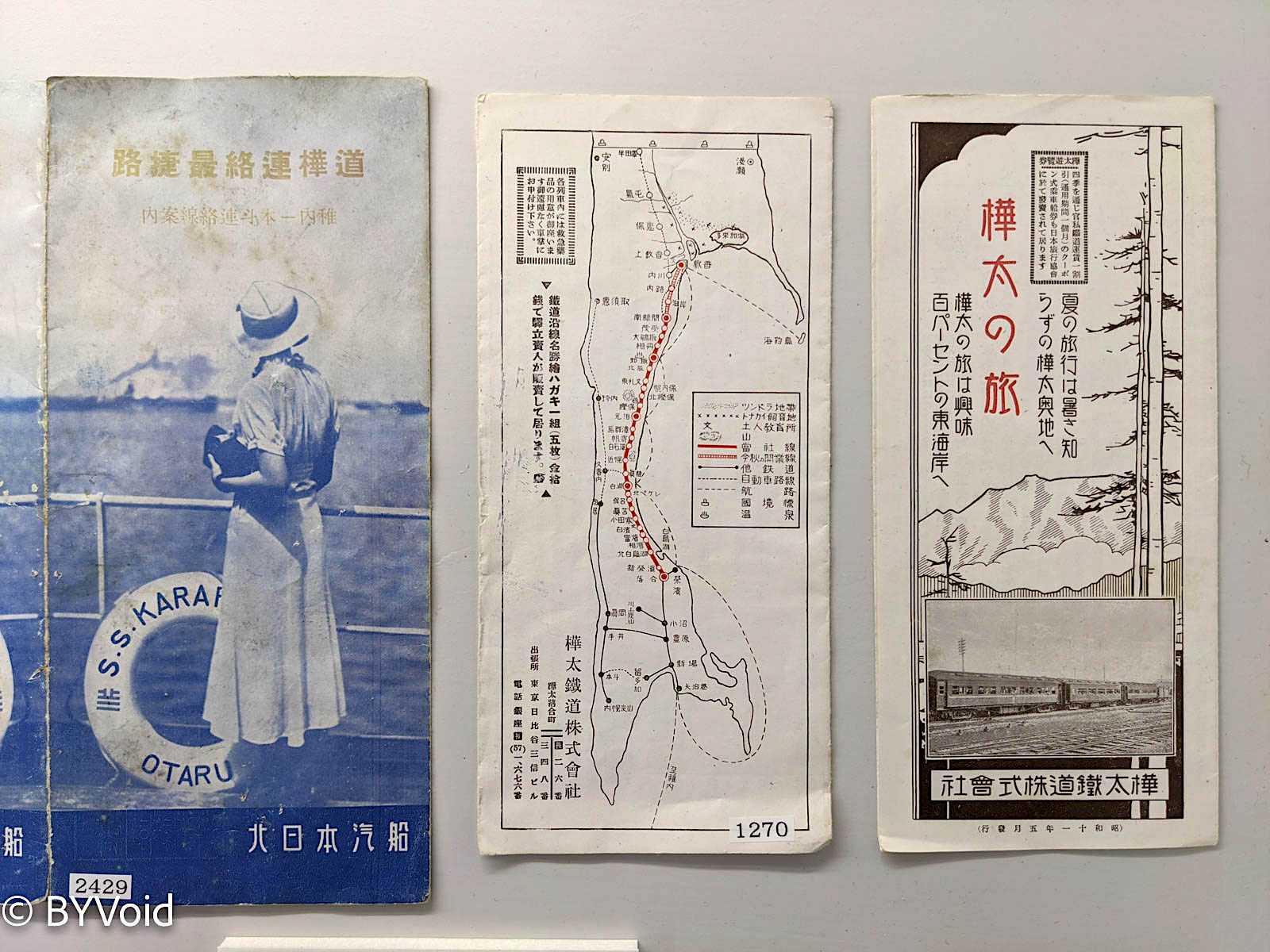

Japan’s claim to Karafuto originated from these two expeditions by Mamiya Rinzo. By the time Japan’s national power was sufficient to support large-scale colonization, the Russian Empire had long been eyeing it covetously. The exhibition on the second floor of the museum is about Japan’s rule over Karafuto, and the content is also very interesting. The display covers the forty years of Japan’s colonial development of South Karafuto from the victory in the Russo-Japanese War to the defeat in the Pacific War, including administrative divisions, railway infrastructure, steamship routes, coal mining, forestry, immigration, and even tourism—truly covering every aspect.

I stayed in the museum for over an hour and still felt like I wanted more.

At the foot of the Memorial Tower hill, there is an observation deck called the “Gate of Ice and Snow” (Hyosetsu no Mon). It is said that you can see Karafuto when the weather is clear. There is a statue of the “Nine Maidens” on the observation deck, showing that for many Japanese coming here to pay their respects, it is not purely for worship but also involves a sentiment of “nostalgia for the lost territory.”

After descending the mountain, I passed through the center of Wakkanai and arrived at the Wakkanai Fukuko Market by the sea. Inside the market, there is another Karafuto Museum. The exhibits in this Karafuto Museum are somewhat similar to those regarding Karafuto in the Centennial Memorial Tower, but the materials are richer, and there are active staff and volunteers attempting to explain the history. notably, the museum houses a “Japan-Russia Border Stone” that was once placed at the 50th parallel north.

In short, one can see that many Japanese have complex emotions regarding Karafuto, which they once colonized. Some groups still refuse to give up their claim to Karafuto, even though this is even more hopeless than reclaiming the “Northern Territories.” Imagine if Japan had not ceded Karafuto; Sakhalin Island today would surely be a completely different scene.

Historically, the struggle for spheres of influence between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire was mainly concentrated in Manchuria and Karafuto. Unlike Manchuria, Karafuto was incorporated into Japan’s “Inland” (Naichi), just like Korea and Taiwan. As for China, not to mention the weakness and poverty of the late Qing Dynasty, even during its prosperous periods, it never had actual control over Sakhalin. The central dynasties generally couldn’t be bothered to govern such remote and barbarous lands, only requiring local tribes to pay tribute, and even the tribute was interrupted at times. However, thriving trade with China did reach here. A very interesting piece of evidence is “Ezo Nishiki” (Ezo Brocade). Ezo Nishiki refers to trade items between the Matsumae Domain (松前藩) of Hokkaido and the Ainu people during the Japanese Shogunate period. These silks were exquisitely textured, woven with dragon patterns and peonies, and were basically Qing Dynasty official robes. In fact, these exquisite official robes originated in Jiangnan, with Suzhou as the distribution center. They were sold to Beijing via the Grand Canal, then transported to the birthplace of the dragon beyond the pass, traveled north along the water network of the Amur River, and sold to the Ainu people of Sakhalin. Finally, the Ainu sold these silks and satins to the Japanese, eventually reaching Edo Castle.

The trade route of Ezo Nishiki is truly breathtaking, and Wakkanai was at the throat of this trade route. In addition to overseas trade, thanks to the ocean currents, Wakkanai also has a very developed fishing industry. The center of Wakkanai still preserves a “Seto Residence,” which was the private residence of a local fishery tycoon in 1952.

After having lunch at Japan’s northernmost train station, I walked to the ferry terminal. The Wakkanai Ferry Terminal has two buildings. One is for international lines, heading to Korsakov (科爾薩科夫) on Sakhalin Island, known as Otomari (大泊) during the Japanese rule. Unfortunately, this passenger route has been suspended for over a year, retaining only a cargo ship that runs a few times a year. I don’t know if there is any hope for restoration in the future. Even in the past, this route was unreliable, always subject to various temporary cancellations. Japan has always said it was due to the capriciousness of the Russian side. But the real reason is probably that there are too few passengers to make it economically viable, and politically there is a lack of motivation for Japan-Russia friendship, so neither government is willing to provide subsidies.

The Floating Island of Flowers: Rebun

Opposite the dilapidated international terminal is the well-maintained Rebun-Rishiri Ferry Terminal, operated by Heartland Ferry, usually with three ferries a day. I bought a ticket from Wakkanai to Rebun for that day, and a ticket from Rebun to Rishiri for the next day. The sea journey of about fifty kilometers from Wakkanai to Rebun took about two hours. There weren’t many passengers on the boat, and even fewer tourists from outside. Usually, July is the golden travel season for Rebun, but this year the coronavirus hit tourism too hard, especially since tour groups had not yet returned, so tourists were scarce. The Japanese have a strong preference for tour groups, which occupy more than half of the market.

I stayed at an Onsen Ryokan (hot spring inn) in Kafuka (香深) on the island, very close to the ferry terminal. After dropping off my luggage, I took advantage of the clearing sky before sunset to climb Momoiwa (Peach Rock/桃巖).

The small town of Kafuka was very quiet. There were only a few Onsen Ryokans and small shops for locals by the sea, and a shrine and a temple in the mountains. It was just a few minutes’ walk to the trailhead. The path wasn’t difficult, and it was clear that someone was maintaining it carefully. After climbing for ten minutes, the vegetation changed from forest to alpine grassland, offering a very open view of both the mountains and the sea.

Seeing that the sun was about to set, I decided to return; Momoiwa would have to wait until the next day.

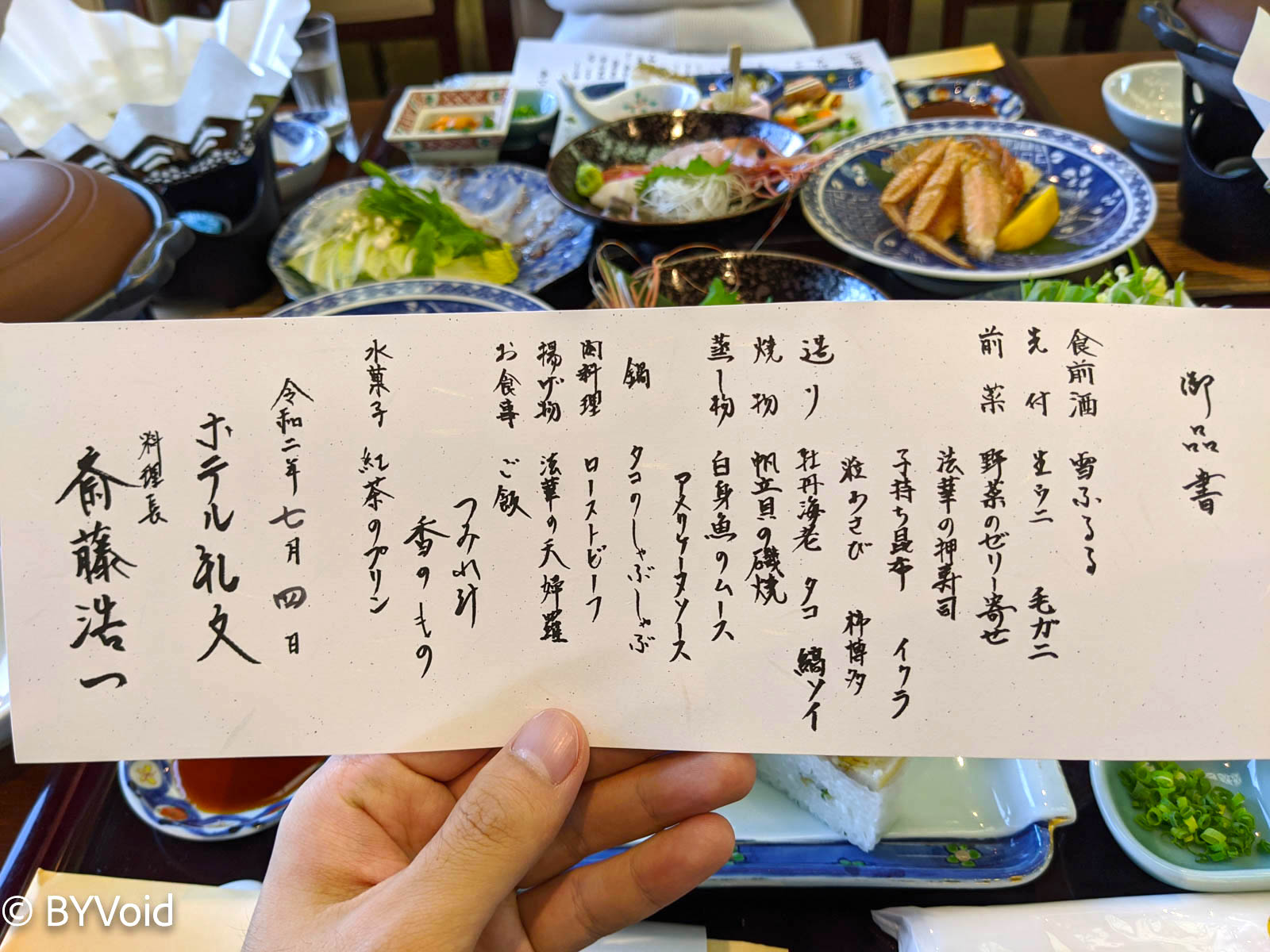

I returned to the Onsen Ryokan at 6:30 PM and began to enjoy dinner. High-end Onsen Ryokans in Japan almost always provide two meals (breakfast and dinner), which is very different from other countries where generally only breakfast is provided. This is because enjoying a carefully prepared Kaiseki meal at the Onsen Ryokan is the most indispensable part of the entire experience.

Situated at the confluence of two ocean currents, Rebun and Rishiri have large fishing grounds nearby, producing abundant cold-water seafood. The most famous are Rebun’s Uni (sea urchin) and Rishiri’s Konbu (kelp). Although Rebun Island is located in a remote area, the abundant catch and relatively mild climate once attracted a large number of immigrants. In the Showa era, the population reached nearly 10,000, but now it is only about 2,000, with a highly aging population.

When I woke up the next morning, the weather was still not very clear, and even Rishiri Fuji was invisible. After eating the exquisite breakfast provided by the ryokan, I rented a car to head to the north side of Rebun Island. Car rental prices on both Rebun and Rishiri remote islands are very expensive, about three or four times higher than in Hokkaido proper. This is likely due to monopoly; I wonder if the local government intentionally restricts it. If you bring your own car, the ferry price is also very expensive, making it worthwhile only if you stay on the island for a long time, whereas most tourists stay for at most two or three days.

Driving from Kafuka to Cape Sukoton (須古頓岬) at the northernmost tip of Rebun Island took over forty minutes. On the way, I saw wild seals on the reefs. Cape Sukoton offers magnificent scenery and is very windy, giving quite a feeling of being at the end of the world. Although Rebun Island is not high in altitude, the vegetation is mainly grassland, with sparse forests.

Driving back from Cape Sukoton, I arrived at the foot of Momoiwa again. Although I easily climbed to the observation deck at the top, the lighting was far inferior to yesterday.

Most residents of Rebun Island live on the east and north sides of the island; there are almost no roads on the west side. There is actually a 1.7-kilometer tunnel between the only settlement on the west side and Kafuka Port. Considering the entire island’s population is only just over two thousand, one has to marvel at the extravagance of Japanese infrastructure.

Viewing Momoiwa from the west, one can understand why it is called Peach Rock. From this angle, the mountain really looks like a plump peach.

Next post: Northern Immortal Islands Part 2.

Last modified on 2021-08-14