Preface: After more than three years, I finally restored the site generator. This article was written in October 2021 as part of my journey “Wandering in Japan” in the Tohoku region.

Tohoku History Museum

Departing from Sendai, a train ride of just over ten minutes brings you to Kokufu-Tagajō Station (Provincial Capital Tagajō Station) on the Tohoku Main Line. The name of this station is derived from the ancient place name “Tagajō” (Tagajo Castle), the “Kokufu” (Provincial Capital) of Mutsu Province (Mutsu-no-kuni) during the Nara period. Exiting from the south gate of the station, the Tohoku History Museum is just a minute’s walk away. The Tohoku History Museum is quite large, with very rich permanent exhibits showcasing archeological remains and historical materials from various eras, ranging from the Stone Age all the way to modern times. The surroundings of the museum are beautiful; it was just the beginning of autumn, and the rain was falling incessantly.

Ancient Tohoku

The archeological history of the Tohoku region in Japan can be traced back to the Paleolithic era, roughly over ten thousand years ago. At that time, it was the Last Glacial Period; the climate was cold, and the sea level was much lower than it is now, so the Japanese archipelago was connected to the Asian continent. The average temperature in Sendai was 7 degrees Celsius lower than today, equivalent to the current climate of northeastern Hokkaido. After the Last Glacial Period, when Japan entered the Jōmon period, temperatures rose significantly, and the sea level became higher than it is today. This period of history is called the “Jōmon Transgression” (Jōmon Kai-shin) era. Following the Jōmon period, a large number of Shell Mounds (Kaizuka) were discovered centering on the Sendai Plain, which are displayed in the museum. Shell mounds are trash heaps formed by humans consuming large quantities of shellfish and discarding the shells. The discovery of shell mounds indicates that large-scale settlements of Jōmon people began to form. A distinct feature of Japanese Jōmon culture is sedentary hunting and gathering, which challenges the traditional anthropological assumption that “agriculture is a necessary condition for settlement.” Later, with the development of archeology, more and more sedentary hunting-gathering cultures similar to the Jōmon culture were discovered; their common point was a superior natural environment. Chiba, Ibaraki, and Miyagi prefectures in Japan are where the most shell mounds have been found, indicating that the Jōmon culture lasted the longest there.

The museum then displays Tohoku during the Yayoi period. Western Honshu and Kyushu entered the Yayoi period first, around the 4th to 5th centuries BCE. The Yayoi period is a landmark event in Japanese history, during which “Toraijin” (people from across the sea) brought advanced farming techniques from the continent by boat to Japan, gradually assimilating the Jōmon people. In the 3rd century BCE, the earliest rice cultivation in Tohoku was discovered at the Sunazawa Site in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture. This indicates that within a century, Yayoi people expanded from Kyushu to northern Honshu. Based on other archeological findings and molecular anthropological evidence, agriculture in Japan may have moved north along the Sea of Japan side before gradually spreading to the Pacific side. In other words, compared to the Kanto Plain, which seemingly looks more suitable for agriculture, Tohoku entered the agricultural age earlier.

Yamato Kingship and Tagajō

In the late 3rd century, western Japan entered the Kofun period (Tumulus period). In Tohoku, the hallmark Keyhole-shaped Kofun (Zenpō-kōen-fun) and Haniwa (terracotta clay figures) began to appear in the latter half of the 4th century. Additionally, pottery manufacturing techniques evolved from the indigenous Haji ware to Sue ware, which was introduced from the Korean Peninsula. During the Kofun period, Japan’s interaction with the continent increased significantly. The Sannō Site in Tagajō yielded bronze mirrors from the 5th century and oracle bones. The usage of these oracle bones is similar to the oracle bones of the the Yin Ruins (Yinxu), involving drilling holes before applying heat to crack them. This oracle bone is quite interesting because the 5th century was already the Northern and Southern Dynasties period in China, more than a thousand years after the Shang (Yin) Dynasty, so it is unknown how the technique was passed down. However, in the late Kofun period, Keyhole-shaped Kofun suddenly disappeared from northern Tohoku. Current research suggests this was likely due to climate cooling between the 4th and 6th centuries, causing agrarian civilization to retreat southward.

In the latter half of the 7th century, the Yamato Kingship finally expanded into Tohoku. “Jōsaku” (fortified government offices) began to appear in various places in Tohoku, which were known as Mutsu Province and Dewa Province. A Jōsaku was a military colonial facility where the Yamato court’s army and officials were stationed. Finally, in the 8th century, in 724 (Jinki Year 1), the Provincial Capital of Mutsu, Tagajō, was officially built. Tagajō was a fortress with walls on flat land, unlike the mountain castles common in the later Sengoku period of Japan. Similar to the square cities of the Chinese mainland, it had gates opening in the east, west, and south directions, with the government office (Seichō) in the center of the castle.

Tagajō is located not far from the museum. Originally, I planned to visit it in person, but the wind and rain were too strong that day, and the original site might have been flooded, so I had to give up.

To the southeast outside of Tagajō, the Tagajō Abandoned Temple (Tagajō-haiji) still exists, named Kanzeon-ji (Temple of Avalokiteśvara). The layout of the Tagajō Abandoned Temple conforms perfectly to the temple layout of the Nara period. Its structure consists of a West Golden Hall, an East Pagoda, and a North Lecture Hall, similar to Hokki-ji in Nara. Furthermore, referring to “Kanzeon” instead of “Kannon” or “Kanjizai” is also a characteristic of early Chinese Buddhism before the Tang Dynasty.

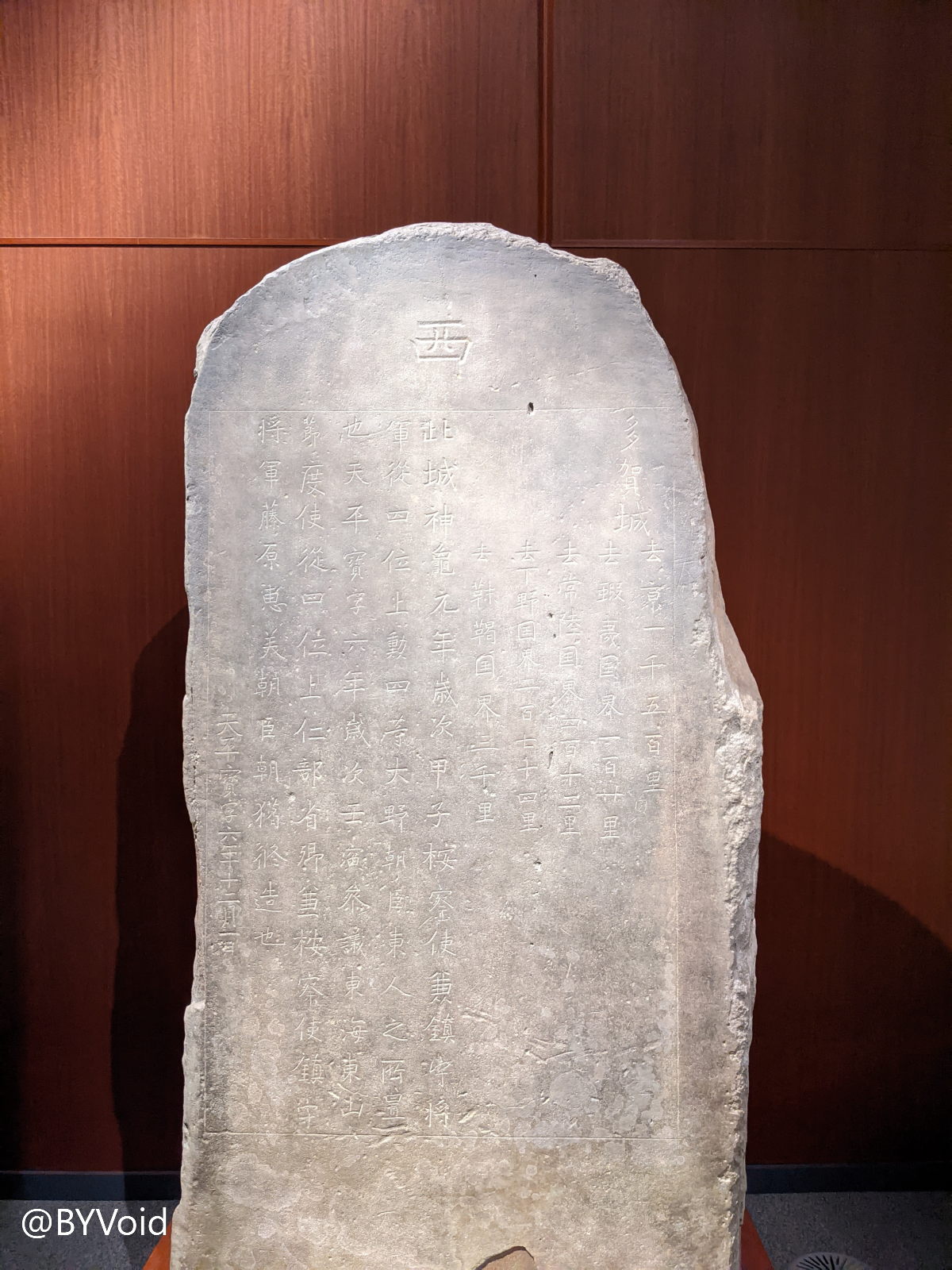

The Tagajō Monument

The most important artifact of Tagajō is the Tagajō Monument (Tagajō-hi), one of the Three Ancient Monuments of Japan, carved in 762 when Tagajō was rebuilt. By the way, there are actually four “Three Ancient Monuments of Japan”: the Tagajō Monument, the Tago Monument, the Nasu-no-Kuninomiyatsuko Monument, and the Ujibashi Monument. Fortunately, the museum exhibited a replica of the Tagajō Monument. The content of the inscription is as follows:

Tagajō Distance to the Capital: 1,500 ri Distance to the border of Emishi country: 120 ri Distance to the border of Hitachi Province: 412 ri Distance to the border of Shimotsuke Province: 274 ri Distance to the border of Mohe Kingdom: 3,000 ri This castle was established in the first year of Jinki, the year of Wood-Rat, by the Azechi and Chinju Shogun, Junior Fourth Rank Upper, Fourth Order of Merit, Ōno no Asom Azumabito. It was repaired in the sixth year of Tenpyō-hōji, the year of Water-Tiger, by the Sangi, Tōkaitōsan Setsudoshi, Minister of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, Azechi, and Chinju Shogun, Fujiwara no Emi no Asom Asakari. December 1st, Sixth Year of Tenpyō-hōji.

The first half of the inscription records the location of Tagajō. The distances are quite accurate, and the statement “Distance to the border of Mohe Kingdom (Makkatsu-koku): 3,000 ri” is particularly striking. This “Mohe Kingdom” is the Bohai Kingdom (Parhae) more commonly seen in historical records. When I visited Kinowano-saku in Sakata, Dewa Province (Wandering in Japan: Sapporo and Sakata), I also saw records of the Bohai Kingdom sending envoys to Japan in 727, showing how close the diplomatic relations were between Japan and the Bohai Kingdom at that time.

The second half of the inscription records the construction time of Tagajō (First Year of Jinki) and the builder (Ōno no Asom Azumabito, i.e., Ōno no Azumabito), as well as the repair time (Sixth Year of Tenpyō-hōji) and the repairer (Fujiwara no Emi no Asom Asakari, i.e., Fujiwara no Asakari).

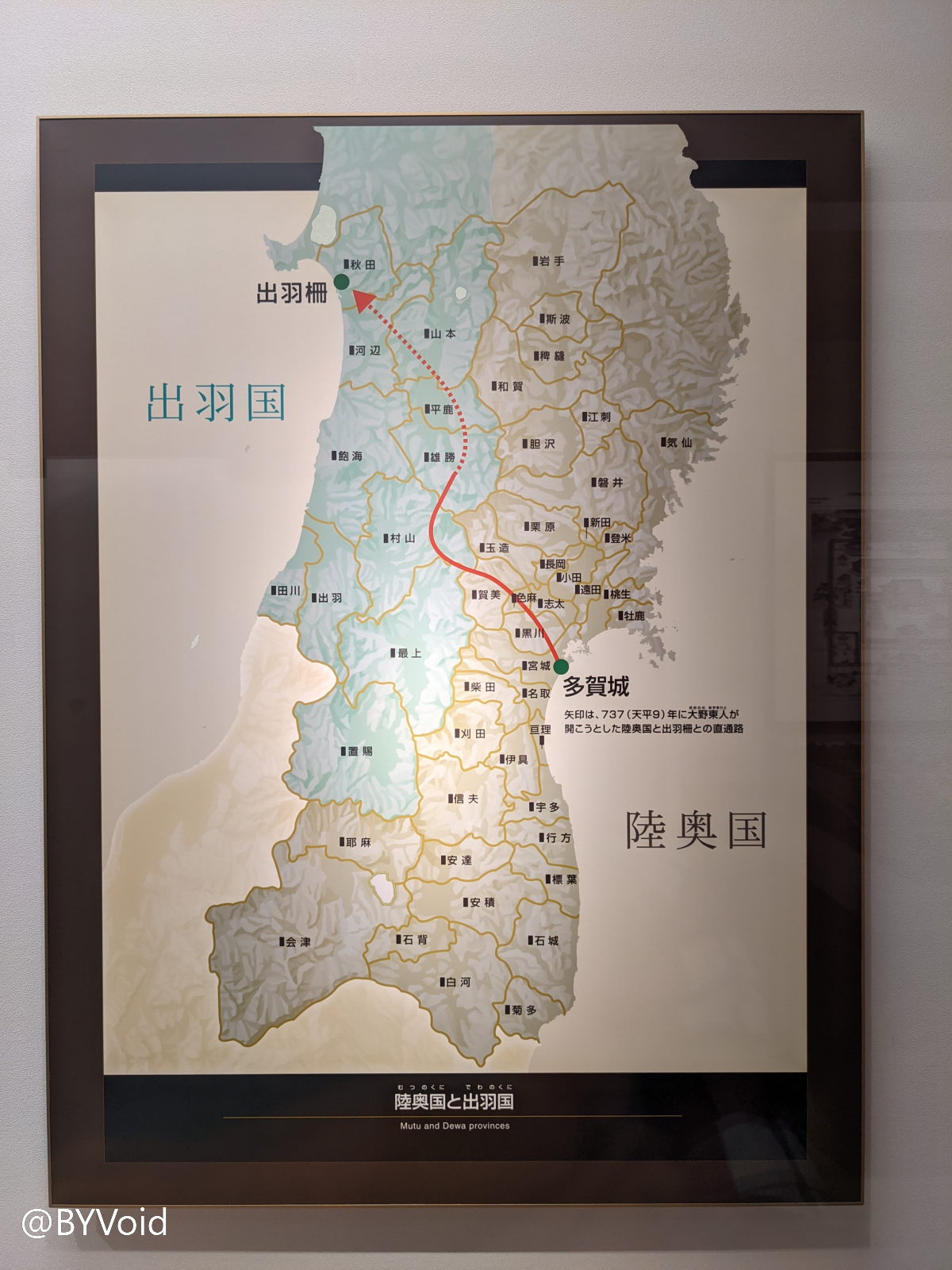

From Mutsu Province to Dewa Province

The museum also introduces that in 737 (9th Year of Tenpyō), Ōno no Azumabito, the builder of Tagajō, opened a road from Mutsu Province to Dewa Province. This was also a milestone event in the colonial history of the Yamato Kingship, marking the extension of the Yamato Kingship’s influence from the coast on both sides to the inland areas. The two frontier Ritsuryō provinces of Japan’s Tohoku, Mutsu Province and Dewa Province, were both located in mountainous areas, so the military colonization on both sides moved north along the coastline. The original writing of Mutsu Province (Michinoku) was “Michinoku-no-kuni” (道奧國), found in the Kojiki, which originally meant the road was rugged and deep.

Tohoku Since the Middle Ages

The next part of the exhibition hall is Medieval Tohoku. An important symbol is the rise of the Northern Fujiwara (Ōshū Fujiwara) clan. After the 11th century, the power of the Yamato court gradually declined, and the Emperor became a figurehead. The officials of the former Ritsuryō provinces slowly developed into local powerful clans, and the Northern Fujiwara clan was a major powerful family centered in Hiraizumi, Mutsu Province. By the early 12th century, Hiraizumi had developed into a metropolis, its prosperity once said to be second only to Heian-kyō (Kyoto). However, all this ended with the Battle of Oshu. According to the records of Azuma Kagami, Shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo, who established the Kamakura Shogunate, captured Hiraizumi and unified the country. Although the Northern Fujiwara clan ceased to exist, many Buddhist temples remain to this day and are now registered as World Cultural Heritage sites. These temples were built according to the worldview of the Pure Land sect (Jōdo-shū) introduced to Japan during the Northern Song Dynasty, including Chūson-ji, Mōtsū-ji, and Kanjizaiō-in. I had specifically visited Hiraizumi once before and was deeply impressed.

After the Kamakura period, Japan gradually moved towards the Sengoku period (Warring States period) of warlord separatism. From the 14th to the 16th centuries, many mountain castles (Yamajiro) appeared in Tohoku as in other places. These mountain castles were military fortresses built by local daimyo forces, not for living, unlike the later flatland castles (Hirajiro) and flatland-mountain castles (Hirayamajiro). Further on was the Edo period, where the Tohoku region was ruled by various domains (Han) and entered a period of relative peace. The theme of the Edo period shifted from war to the daimyo’s Sankin-kōtai (alternate attendance) and rising trade. The western and eastern routes of the Kitamaebune (northern-bound ships) turned Sakata and Ishinomaki into trade centers respectively. During this period, like in China and Korea, Buddhism was replaced by Neo-Confucianism (Cheng-Zhu school, Lu-Wang school) as the culture favored by the samurai class, and each domain established domain schools (Hankō). Like all historical museums in Japan, the last part of the exhibition is the Meiji Restoration and the Boshin War, as well as the subsequent “Civilization and Enlightenment” (Bunmei Kaika).

The Frontier of Yamato Civilization

In conclusion, perhaps due to personal interest, I think the most worth-seeing part of this museum is the early Japanese history from the Jōmon period to the early Heian period, because Mutsu Province at that time still belonged to the frontier zone of Yamato civilization and had not yet completed “Yamato-ization”. Looking at the density of the Ritsuryō province divisions in the Nara period, it is easy to find that Japan from northern Kyushu to the Kanto Plain was covered by dense Ritsuryō provinces, while the vast Tohoku only had two undefined frontier lines: Mutsu Province and Dewa Province. Although Ritsuryō provinces were called “countries” (kuni), they were closer to the commanderies and counties of China’s unified dynasties, while the “Han” (domains) born after the decline of kingship in later generations were more like the feudal states of pre-Qin China. Where the Ritsuryō provinces reached was where the Yamato Kingship reached, so it can be inferred that the east-west cultural integration of Japan at that time was nearing completion. From the repeated advance and retreat of the farming line in the Kofun period to the war between the Seii Taishōgun (General who Subdues the Barbarians) and the Emishi, it reflects the difficulty of expansion across climate zones. The Tohoku dialects, which are the most complex and difficult to understand in Japanese, also reveal this heterogeneity. Moreover, hunter groups like the “Matagi” who did not engage in farming existed in Tohoku until modern times. In fact, Japan did not completely assimilate Tohoku until the Meiji Restoration, after incorporating Hokkaido and even Karafuto (Sakhalin) and Chishima (Kuril Islands) into its territory.

The history of Japan’s Tohoku is a history of the Yamato people expanding northward; this is where the uniqueness of Japan’s Tohoku lies.

Tagajō Abandoned Temple

Walking out of the history museum, the wind and rain were still strong. Helplessly, I gave up on seeing the Tagajō ruins. However, I braved the rain and ran to the nearby ruins of the Tagajō Abandoned Temple. Although there are no buildings above ground at this site, the underground structure is relatively complete, with foundations for the Golden Hall, Buddhist Pagoda, and Lecture Hall, and pillar base stones can still be seen on the foundations.

Last modified on 2025-11-10