What is Historical Kana Orthography

The standardization of modern Japanese actually does not have a long history; it was essentially fixed after World War II. Although the degree of “Genbun-itchi” (unification of spoken and written language) in Japanese might still not be considered high, it has been significantly simplified compared to the past. After WWII, Japan, under Allied control, initiated language and script reforms. The most well-known of these is the “Tōyō Kanji” (List of Kanji for Interim Use) of 1946. Under American supervision, the new Japanese government proposed the Tōyō Kanji, which regulated the scope of Kanji usage, solidified the status of simplified characters (Shinjitai), allowed for the replacement of rare characters with homophones, and established principles for mixing Kanji and Kana. Although there were many subsequent amendments, the fundamental tone remained unchanged.

Also in 1946, the Japanese Language Council carried out a drastic reform of Kana usage, known as “Modern Kana Usage” (Gendai Kanazukai). Compared to the Kanji reform, the Kana usage reform was the more fundamental change. “Kana usage” (Kanazukai) refers to the method of using Kana; in more general linguistic terms, it is Orthography, a set of conventions for transcribing speech into writing.

Different languages handle this differently: some have official standard orthographies (like German), while others have only prevailing norms (like English). Languages that have undergone standard orthography reforms generally tend towards a lower orthographic depth (the degree to which the written form deviates from a one-to-one correspondence between individual letters and phonemes). Lower orthographic depth makes spelling and reading aloud easier (though it does not necessarily make recognition/comprehension easier). For example, the letter ‘a’ in German represents the phoneme /a/ in almost all contexts, whereas the English ‘a’ has several irregular readings. Through the Modern Kana Usage reform, the orthographic depth of Japanese Kana was reduced somewhat, but it still has not reached a 100% one-to-one correspondence.

So, what exactly is Historical Kana Orthography (Japanese: 歴史的仮名遣ひrekishiteki kanadukahi)? In a nutshell, it is the Kana writing norm that naturally continued from the Heian period until the Japanese orthography reform of 1946. Compared to Modern Kana Usage, Historical Kana Usage contains a large number of homophonous Kana, which embody historical phonological shifts. If you are interested in historical phonology, understanding Historical Kana Orthography is essential.

Rules of Change in Historical Kana Orthography

It is impossible to directly deduce Historical Kana Usage from Modern Kana Usage because Modern Kana Usage has merged a large number of Kana that have become homophonous in standard Japanese. This section introduces the differences between Modern and Historical Kana Usage, touching upon historical Japanese phonological changes, and deduces the rules of change for Sino-Japanese Historical Kana Usage through the phonology of Middle Chinese (Guangyun).

“ゐ” (Wi) and “ゑ” (We)

Like many others, my first contact with Historical Kana Orthography was probably through the Kana “ゐ” and “ゑ”. These two Kana correspond to the ‘i’ segment and ’e’ segment of the ‘wa’ row in the fifty-sound table (Gojūon). In Modern Kana Usage, “ゐ” and “ゑ” have been merged into “い” (i) and “え” (e) respectively.

For example:

- The native word “居る” (to be) is written as “ゐる” in Historical Kana Usage. The Sino-Japanese sound for characters in the Guangyun ‘Zhi’ rhyme group, closed-mouth (Hekouhu) is “ゐ” (wi), such as “威”, “胃”, “維”, etc.

- The native word “聲” (voice) is written as “こゑ” in Historical Kana Usage. The Sino-Japanese word “自衛” (self-defense) is “じゑい”, “智慧” (wisdom) is “ちゑ”, and “圓” (yen/circle) is “ゑん”.

One point that is slightly unclear concerns characters outside the ‘wa’ row (non-zero onset) of the ‘Zhi’ rhyme group closed-mouth, such as “水” (water) and “類” (category). Some dictionaries write them as “すい” and “るい” in Historical Kana Usage, while others write “すゐ” and “るゐ”. Given that the zero-onset is written as “ゐ”, I tend towards the latter. However, these two represent the same phoneme and there is no contrastive distinction.

Additionally, Kana for the Wa-row U-segment (“wu”) might also exist, but because they are excessively rare in historical documents, Unicode has not included them. There is a personal research article that explores this issue in detail.

A-row Changes

Besides “ゐ” and “ゑ”, which have been merged and abolished, the A-row “い”, “う”, “え”, “お” have also merged with the corresponding Kana from the Ha-row and Wa-row.

Specifically, the “い” in Modern Kana Usage may come from “い”, “ゐ”, or “ひ”; “う” may come from “う” or “ふ”; “え” may come from “え”, “ゑ”, or “へ”; “お” may come from “お”, “を”, or “ほ” (and even “ふ”, for example “倒れる” is written as “たふれる”).

Apart from the aforementioned “ゐ” and “ゑ”, the merged Ha-row Kana “ひ”, “へ”, “ほ” are mostly found in native Japanese words (Wago), while “ふ” appears in some Sino-Japanese entering tone characters, which will be mentioned later.

Ka-row Gōyōon (Closed-mouth Palatalized Sounds)

Some Sino-Japanese words with “か” and “が” in Modern Kana Usage are written as “くわ” (kwa) and “ぐわ” (gwa) in Historical Kana Usage. These Kana are called Gōyōon (or Kw- sounds). Characters written with Gōyōon in Historical Kana Usage strictly correspond to the closed-mouth (Hekouhu) of the Velar initials (Jian, Xi, Qun, Yi groups) in Guangyun initials. For example, “化” is “くわ”, “外” is “ぐわい”, “月” is “ぐわつ”, and “願” is “ぐわん”.

The historical spelling “くわ” still survives in the Latin script transliteration of some proper nouns, such as “Hongwanji (本願寺)”.

Yotsugana (The Four Kana)

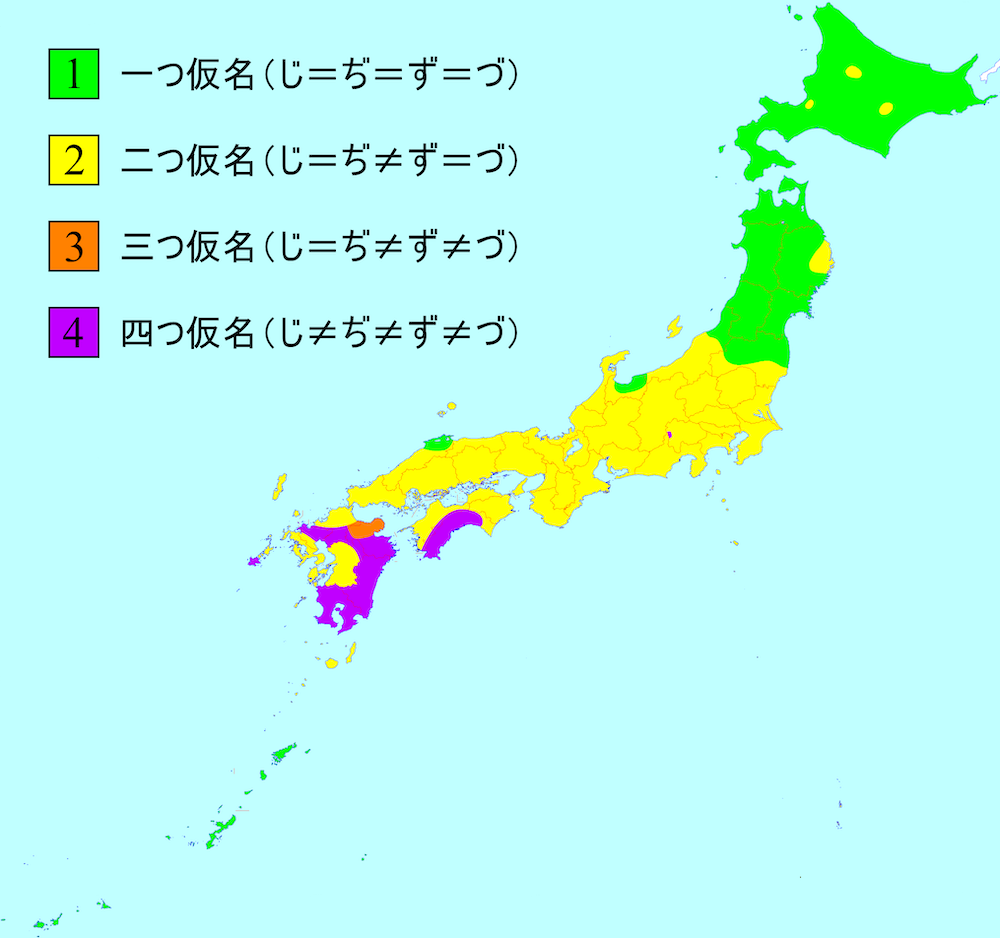

“Yotsugana” refers specifically to the four voiced Kana: “じ” (ji), “ぢ” (di/ji), “ず” (zu), and “づ” (du/zu). According to research, “じ” and “ぢ”, as well as “ず” and “づ”, began to show trends of confusion starting in the Kamakura period (13th century), primarily accompanying the affrication of “ち” and “つ” from /ti/, /tu/ to /ʨi/, /ʦu/. Later, although “じ” and “ず” were voiced fricatives and “ぢ” and “づ” were voiced affricates, the two categories completely merged in the common language by the Edo period.

According to dialect surveys in the Showa era after the war, there were still dialects in Japan that could distinguish all four categories, as well as those that could distinguish three, mostly concentrated in the Kyushu and Shikoku regions. At the same time, there were dialects, mainly in Tohoku and Hokkaido, that merged all four Kana into a single category.

The Modern Kana Usage reform, based on the Kanto and Kansai sounds, abolished “ぢ” and “づ”. Except for Rendaku (sequential voicing) and proper nouns, they were uniformly merged into “じ” and “ず”.

Ha-gyō Tenko (Ha-row Shift)

Ha-gyō Tenko refers to the lenition of Ha-row Kana consonants, becoming the corresponding A-row or Wa-row Kana. According to research, Ha-gyō Tenko occurred quite early, possibly starting in the Heian period.

When not word-initial, Ha-row Kana underwent two changes: from Ha-row to Wa-row, and then to A-row. For example: “上” (above) “うへ” -> “うゑ” -> “うえ”; “顏” (face) “かほ” -> “かを” -> “かお”. Verbs that end in “-う” in Modern Kana Usage all end in “-ふ” in Historical Kana Usage, e.g., “買ふ” (to buy), “吸ふ” (to suck), “遣ふ” (to use).

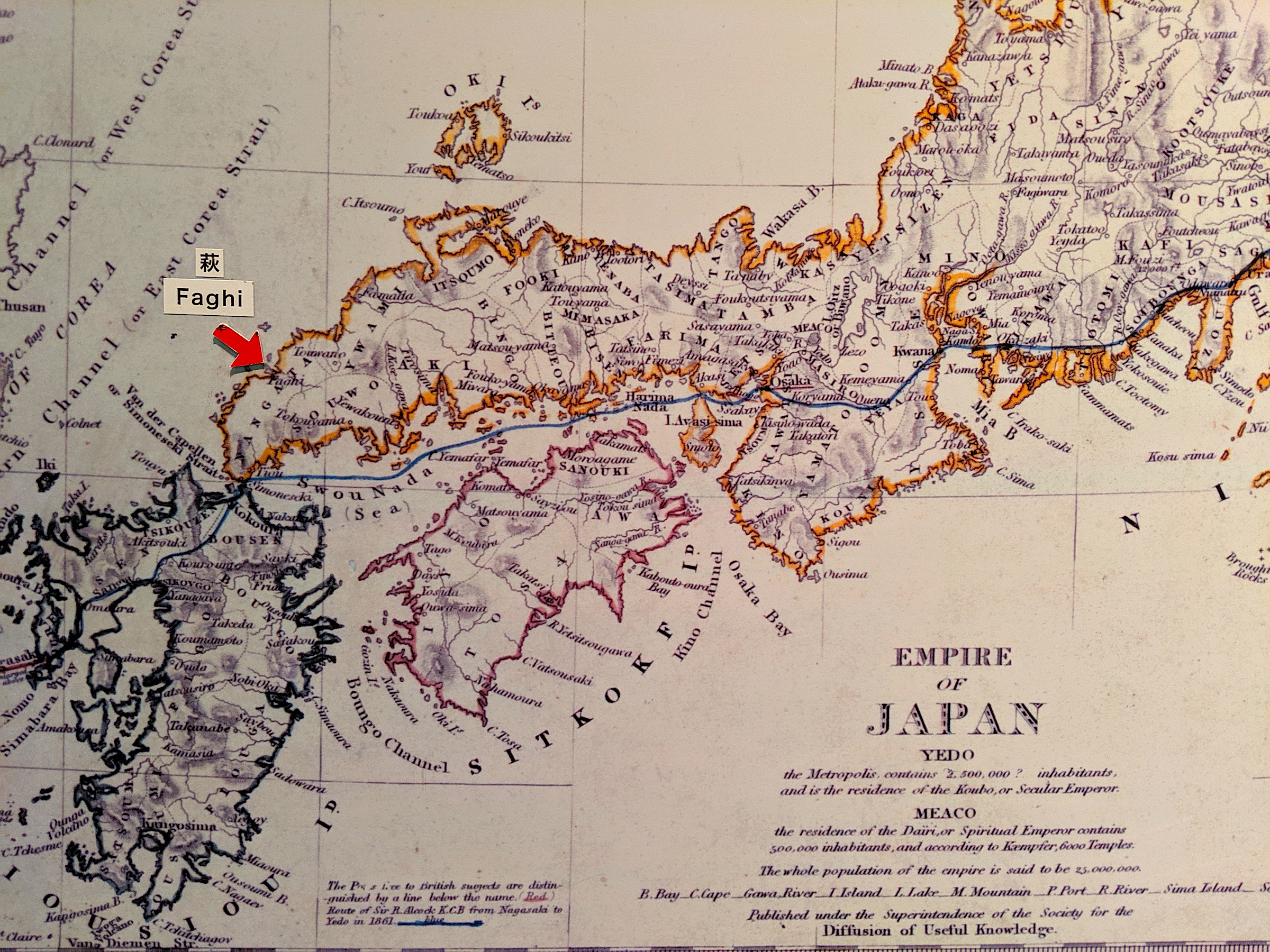

The pronunciation of Ha-row Kana at the beginning of words also underwent a change from /p/ to /ɸ/ and then to /h/. One piece of evidence is the text and maps left by Europeans trading in Japan during the Edo period. In the map below, “萩” (Hagi) is written as “Faghi”, “甲斐” (Kai) as “Kafi”, “播磨” (Harima) as “Farima”, while “播磨灘” (Harima Nada) is written as “Harima Nada”, vividly recording the phonological flux.

“-ふ” Entering Tone

The change of the suffix “ふ” to “う” in Sino-Japanese words is also part of the Ha-row shift.

If you are familiar with Cantonese, Korean, or Middle Chinese, it is easy to know that Japanese preserves complete -k and -t consonant codas for entering tone characters. However, -p entering tone characters are not as obvious in Japanese because most -p entering tone characters turned into -u long vowels, and a few mixed with -t (e.g., “立” is read “りつ”, but “建立” is “こんりゅう”). These -p entering tone characters only occasionally appear during gemination (sokuon), for example “合體” is read “がったい”, “十分” is “じっぷん” (also “じゅうぶん”, but the meaning differs), and “入聲” is “にっしょう”.

-p entering tone characters are very clear and distinct in Historical Kana Usage, consistently ending in “-ふ”. Examples are given in the long vowel list below.

Long Vowel Change Table

Now, we finally reach the section on Modern Kana Usage long vowels, which is the most complex part of Historical Kana Usage. This is because almost every long vowel ending in -u in Modern Kana Usage merges several different sources (-uu is an exception, e.g., “空くう”, “風ふう”). I divide these differences into three major categories, based on their Modern Kana Usage endings: -ou, -yuu, and -you. Each major category is further divided into subcategories based on origin.

It is important to note that Modern Kana Usage introduced smaller characters, such as “きゅ”, to represent a contracted sound (Yōon) occupying one mora. However, in Historical Kana Usage, every phoneme is a normal-sized Kana and does not strictly occupy one mora, e.g., “きやう”. As for how exactly syllables were divided in Heian period Japanese, I am not familiar with the issue; perhaps it can be inferred from ancient Haiku. Furthermore, the geminate consonant marker (Sokuon) is not written with a small character, but with a normal “つ”.

-ou

In Modern Kana Usage, all non-Yōon long vowels invariably end in -ou. In Historical Kana Usage, these can be divided into four categories. The codas are u and fu, and the main vowels are a and o.

The following table lists all combinations. Blank cells indicate no sound from Chinese; parentheses indicate no commonly used Kanji. For combinations with voiced sounds, I have listed the voiced sound in the second line of each cell. Note that semi-voiced sounds are not listed because they only arise from Rendaku.

The sources of -au in Guangyun fall into two categories (assuming Kan-on unless otherwise specified): some are Xiao rhyme group Division I/II characters, and some are Dang rhyme group Division I characters. -ou are mostly Dong rhyme Division I characters and Deng rhyme Division I characters. -afu comes from Xian rhyme group Division I/II entering tone characters. -ofu characters are very few, basically from the Ye and Fa rhymes of the Xian group.

| Modern Kana Usage | -au | -ou | -afu | -ofu | |

| A-row | おう | あう 央 |

おう 應 |

あふ 押 |

|

| Wa-row | おう | わう 王 |

|||

| Ka-row | こう ごう |

かう 康がう 號 |

こう 公ごう 藕 |

かふ 甲がふ 合 |

こふ 劫ごふ 業 |

| Ka-row Gōyōon |

こう ごう |

くわう 光ぐわう 轟 |

|||

| Sa-row | そう ぞう |

さう 草ざう 象 |

そう 送ぞう 增 |

さふ 插ざふ 雜 |

|

| Ta-row | とう どう |

たう 刀だう 堂 |

とう 東どう 動 |

たふ 塔(だふ) |

|

| Na-row | のう | なう 腦 |

のう 能 |

なふ 納 |

(のふ) |

| Ha-row | ほう ぼう |

はう 包ばう 望 |

ほう 奉ぼう 貿 |

はふ 法ばふ 乏 |

ほふ 法ぼふ 法 |

| Ma-row | もう | まう 猛 |

もう 蒙 |

||

| Ra-row | ろう | らう 勞 |

ろう 樓 |

らふ 臘 |

(ろふ) |

-yuu

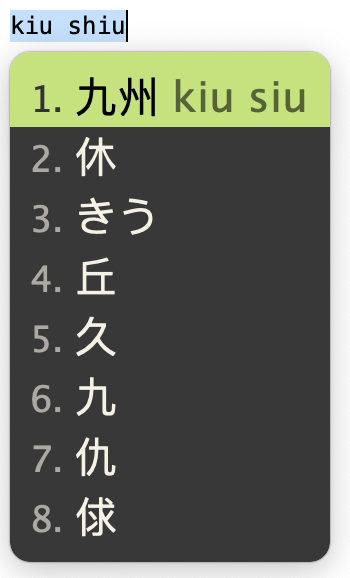

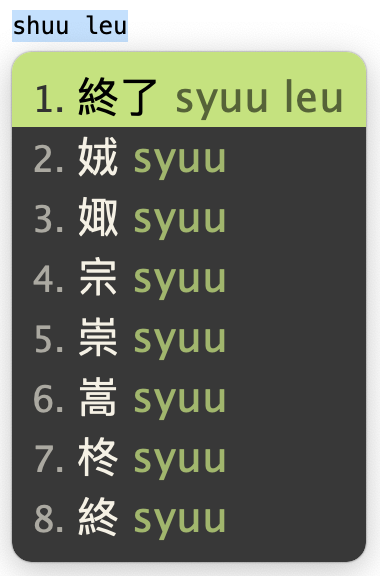

The -yuu contracted sounds in Modern Kana Usage fall into three categories in Historical Kana Usage: -iu, -yuu, and -ifu. Among them, -iu are basically all Liu rhyme group Division III characters, while -yuu corresponds to Dong rhyme Division III characters; the two are very easily distinguished via modern Mandarin. -ifu corresponds to Shen rhyme group entering tone characters.

Reading literally, -iu and -yuu seem hard to distinguish. But if we must reconstruct, we can refer to Vietnamese ui and uy, distinguishing them by the length difference between the main vowel and the coda within the syllable.

| Modern Kana Usage | -iu | -yuu | -ifu | |

| A-row/Ya-row | ゆう | いう 有 |

ゆう 勇 |

いふ 邑 |

| Ka-row | きゅう ぎゅう |

きう 休ぎう 牛 |

きゆう 宮 |

きふ 急 |

| Sa-row | しゅう じゅう |

しう 州 |

しゆう 終 |

しふ 習じふ 十 |

| Ta-row | ちゅう じゅう |

ちう 宙ぢう 糅 |

ちゆう 中ぢゆう 重 |

|

| Na-row | にゅう | にう 柔 |

にゆう 乳 |

にふ 入 |

| Ha-row | ひゅう びゅう |

ひう 彪びう 謬 |

||

| Ra-row | りゅう | りう 留 |

りゆう 隆 |

りふ 立 |

-you

Modern Kana Usage -you has four sources: -yau, -you, -eu, -efu. The sources of -yau and -you are both -ng ending nasal rhyme characters. Roughly corresponding, -yau (Go-on) comes from all Geng rhyme group and Dang rhyme group Division III. -you comes from parts of Tong rhyme group Zhong rhyme Division III and Zeng rhyme group Division III. -eu corresponds quite clearly to Xiao rhyme group Division III/IV and some Division II characters. -efu comes from most Xian rhyme group Division III/IV entering tone characters.

In Japanese long vowels corresponding to the -ng rhyme ending, the difference between Go-on and Kan-on for Geng rhyme group Division III/IV is most obvious, and for many characters, both Go-on and Kan-on are commonly used. Generally, Go-on is -yau (e.g., “平びやう等” - byoudou/equality), while Kan-on is -ei (e.g., “平へい和” - heiwa/peace).

| Modern Kana Usage | -yau | -you | -eu | -efu | |

| A-row/Ya-row | よう | やう 陽 |

よう 用 |

えう 要 |

えふ 葉 |

| Wa-row | よう | ゐやう 永 |

|||

| Ka-row | きょう ぎょう |

きやう 兄ぎやう 行 |

きよう 共ぎよう 凝 |

けう 教げう 曉 |

けふ 協げふ 業 |

| Ka-row Gōyōon |

きょう | くゐやう 兄 |

|||

| Sa-row | しょう じょう |

しやう 商じやう 上 |

しよう 勝じよう 冗 |

せう 少ぜう 擾 |

せふ 捷 |

| Ta-row | ちょう じょう |

ちやう 長ぢやう 丈 |

ちよう 徵(ぢよう) |

てう 朝でう 條 |

てふ 蝶でふ 疊 |

| Na-row | にょう | (にやう) | によう 女 |

ねう 尿 |

|

| Ha-row | ひょう びょう |

ひやう 評びやう 病 |

ひよう 冰(びよう) |

へう 表べう 秒 |

|

| Ma-row | みょう | みやう 名 |

(みよう) | めう 妙 |

|

| Ra-row | りょう | りやう 領 |

りよう 陵 |

れう 料 |

れふ 獵 |

The above constitutes the entirety of Historical Kana Orthography.

About “-む” (-mu)

Since Historical Kana Usage does not have a single unique standard, you may sometimes see different dictionaries or documents using different markings. The previously mentioned “water” recorded as “すい” or “るい” is one example.

Another common difference is that some documents use “-む” to indicate the syllabic nasal (Modern Kana Usage is always “ん”). For example, “三” (three) is recorded as “さむ”, corresponding to the -m coda of Middle Chinese. This notation mainly comes from Motoori Norinaga’s “Jion Kana Zukai” (rules for Kana usage of Sino-Japanese sounds) in the Edo period, and some dictionaries have inherited it, such as Kanjigen.

Problems with Modern Kana Usage

The Modern Kana Usage reform was a significant attempt, rooted ideologically in the wave of script reforms that swept the world in the first half of the 20th century. The basic philosophy of this global wave of reform was simplification and phonetization, aiming to simplify orthography and achieve the unification of speech and writing.

Through this reform, individual Kana indeed became easier to read. However, due to the heavy historical baggage of Kanji—or perhaps we should call it rich cultural accumulation—written Japanese remains one of the most difficult written languages to read in the world, not only for foreign learners but also for native Japanese speakers. Even for “Text-to-Speech (TTS)” algorithms, Japanese is deservedly the most difficult stronghold to conquer. Without the ability to abolish Kanji, reforming Kana does not make Japanese much easier to learn. Whether for Japanese elementary school students or foreigners learning Japanese, mastering the spelling of Historical Kana Usage is not inherently difficult. For the goal of “simplifying written Japanese,” the Modern Kana Usage reform is merely a drop in the bucket.

Even with Modern Kana Usage, Japanese Kana has not achieved a one-character-one-sound system:

- Grammatical particles “は” (wa), “へ” (e), “を” (o) are retained, but their pronunciation differs from the Kana itself.

- “ぢ” (di/ji) and “づ” (du/zu) have not been completely abolished; they are retained in morphemes during Rendaku.

- Long vowels remain unintuitive, with three methods of representation: the long vowel mark “ー”, ending in “-う” or “-い”, and repeating the Kana. The pronunciation of the three is no different, but the writing differs. For example:

- オークション (Auction), イーユー (EU)

- 往々

おうおう(ou-ou / ōō), “映畫”えいが(eiga / ēga) - 大阪

おおさか(Oosaka / Ōsaka), ええ (ee)

- “-おう” at the end of a word does not necessarily indicate a long vowel; in verbs like “争う

あらそう” (arasou), it is not a long vowel.

While not bringing much convenience, Modern Kana Usage has to some extent severed links with history and tradition. Without knowledge of Historical Kana Usage, the difficulty of reading early modern literature increases sharply. Due to the massive merger of homophonous Kana, text written purely in Kana has become harder to read rather than easier, forcing readers to rely even more on Kanji. The post-war reform limiting Kanji usage and Modern Kana Usage itself have contradictory aspects. For Japanese learners (including native speakers), the difficulty of mastering the conjugation of classical language (Bungo) also increases, eventually necessitating the study of Historical Kana Usage anyway. Modern Kana Usage perfectly fits the modern Kanto sound, thus losing the ability to be compatible with other dialects, accelerating the disappearance of Japanese dialects.

How to Read Historical Kana Orthography

First, is Historical Kana Orthography Ancient Japanese? The answer is no. Historical Kana Orthography is merely a writing norm that has continued from ancient times to the present; the content written need not be restricted to the ancient style, including grammar and vocabulary. Referencing English, which has not undergone orthographic reform, there is no problem writing modern English using inherited norms.

Second, is Historical Kana Orthography the pronunciation of a specific era in Japan? The answer is also no. Historical Kana Orthography was not born at a single moment but is an implicit norm passed down naturally. It can only be said that Historical Kana Orthography reflects many phonological characteristics of the Heian period, but this does not mean that reading it literally produces the pronunciation of the Heian period. Again taking English as an example: vowel letters in most English words are assigned based on pronunciation before the 15th-century Great Vowel Shift. For example, “make” is read as /meɪk/ in modern English, but one cannot conclude that reading it as /maːke/ by the letters represents the actual pronunciation of Middle English. A vast vocabulary in daily English was coined or entered English from other languages after the 15th century, so one definitely cannot simply deduce pronunciation by reversing the Great Vowel Shift based on spelling. Of course, as a hobby for a small group, reading literally according to Historical Kana Usage is not impermissible.

Furthermore, Historical Kana Usage has been constantly changing throughout history, just as Sino-Japanese sounds have multiple layers, rather than a unified standard. Although there were attempts at regularization in the Kamakura period (“Teika Kanazukai”) and the Edo period (“Keichū Kanazukai”), these were different from the mandatory reform of Modern Kana Usage.

Therefore, the way to read Historical Kana Orthography should be the same as Modern Kana Usage: read according to actual (modern) pronunciation. Japan in 1946 merely carried out an orthographic reform, not a “phonetic reform”.

How to Look Up Historical Kana Orthography

If you are looking up Sino-Japanese sounds, I highly recommend the “Mcpdict” (Chinese Character Readings: Ancient, Modern, and Foreign) app. Here you can find not only the Historical Kana Usage for the Go-on, Kan-on, Tō-on, and Kan’yō-on of every Kanji, but also pronunciations in Korean, Vietnamese, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Min Nan.

If you want to look up native Japanese words (Wago) and different definitions, you can use the “Weblio National Language Dictionary”. Small characters follow the Kana of each entry; if it differs from Modern Kana Usage, its Historical Kana Usage will be noted.

How to Type Kanji Using Historical Kana Orthography

Given that Modern Kana Usage has so many problems, how can we type in Historical Kana Usage?

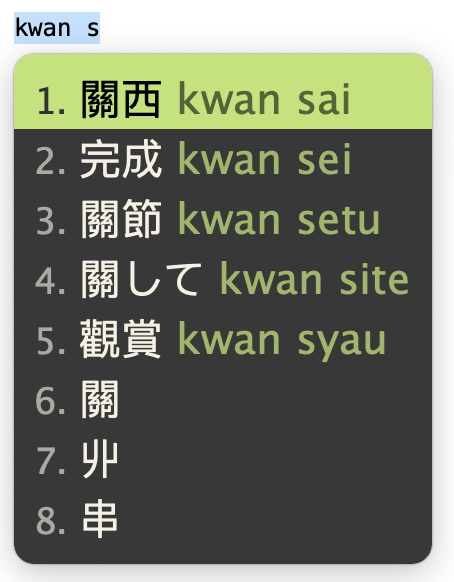

Fortunately, there is the Rime Input Method by Fo Zhen. Biopolyhedron has contributed a Japanese Historical Kana Usage input method based on the Rime platform. Here is my forked version. Installing Rime input schemas can be a bit complex and requires some technical knowledge; please refer to the documentation for details. Here is an example configuration file.

Below is the effect of typing “kou efu”:

Distinguishing “しう” (siu) and “しゆう” (siyuu):

Supports basic auto-completion:

To maintain mora timing, Biopolyhedron’s scheme outputs Gōyōon using “くゎ” and Sokuon using a small “っ”. However, true Historical Kana Usage does not use small letters.

Note that this is just a toy and cannot replace a standard Japanese input method. The main reason is that the dictionary is very small, and there is no conversion for native Japanese Kun-yomi. With it, you can only input Kana and Kanji via Sino-Japanese sounds, and it is basically character-based, lacking character or word frequency data. Of course, if needed, I could import data from other sources to enrich it and make it truly usable.

Conclusion

This article introduced the concept of Historical Kana Orthography and some major rules of change. The introduction of change rules focused on the Kan-on of Sino-Japanese words. The rules for Historical Kana Usage of native Japanese words are more irregular and were touched upon less in this article. If interested, you can continue reading the article “Seikana Hayawakari” (Quick Understanding of Correct Kana Usage).

References

- Agency for Cultural Affairs: Cabinet Notification/Cabinet Instruction on Modern Kana Usage

- Wikipedia “Modern Kana Usage”

- Biopolyhedron’s Study Notes on Historical Kana Usage

- Quick Understanding of Correct Kana Usage

- Phonological changes seen in the Entering Tone P-sound Euphony

- Ytenx (Rhyme Dictionary Network)

Acknowledgements

Last modified on 2020-05-07