In late March, while the virus seemed to be spreading rapidly elsewhere in the world, Japan mysteriously had the outbreak under effective control. Although uncertainty caused violent fluctuations in financial markets, Japan seemed able to stay out of it. At this time, a state of emergency had not yet been declared, Japan had not locked down any cities, traffic was normal, and there were quite a few people on the streets near Shibuya. I decided to set out as planned; after this, I hardly went out again until mid-June.

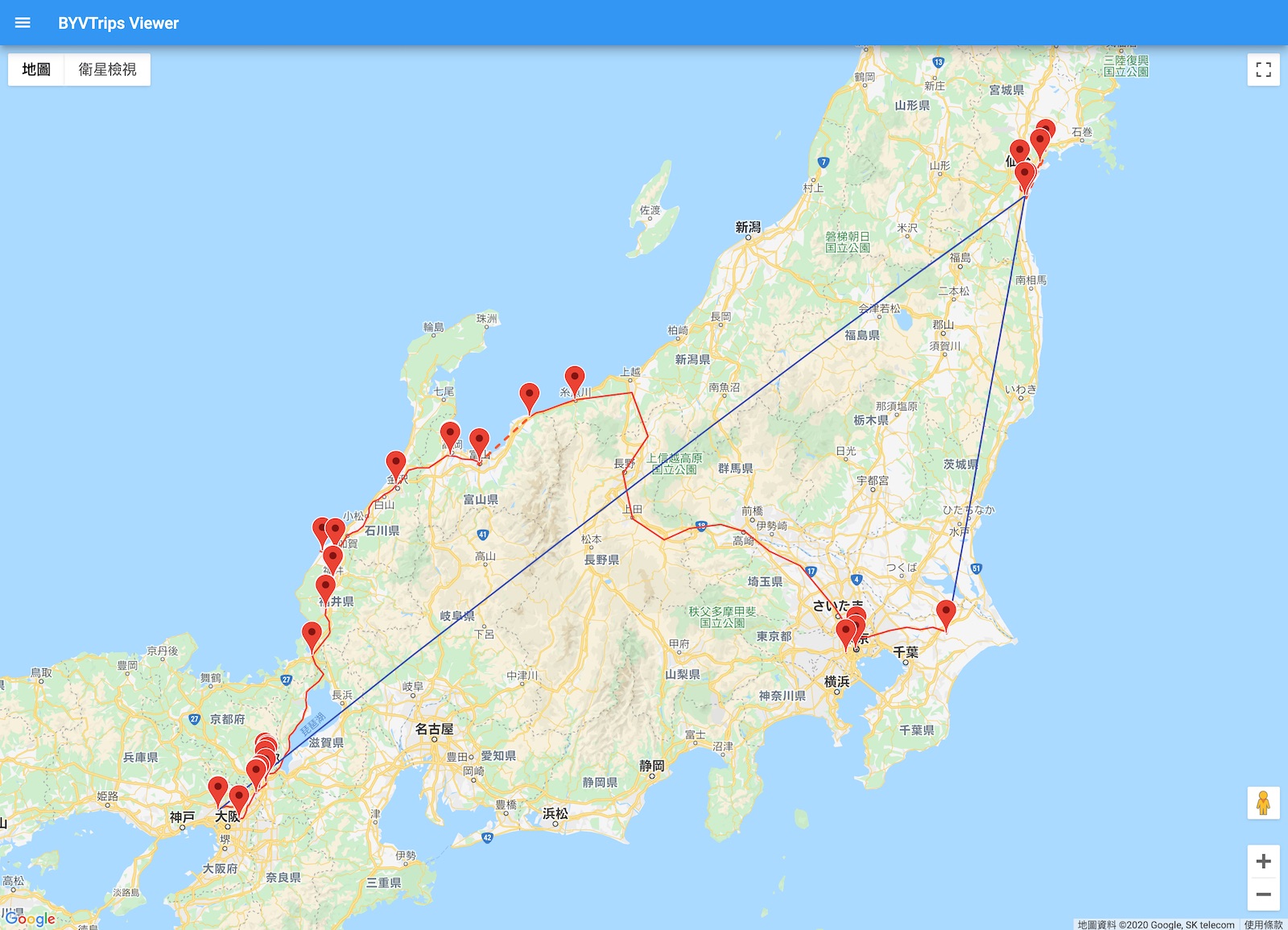

Taking advantage of a three-day holiday, I first departed from Narita Airport, visited Matsushima near Sendai, then went straight to Osaka, circled around Hokuriku, stopping in Fukui, Takaoka, Toyama, and finally took the Hokuriku Shinkansen back to Tokyo.

Day 1: Matsushima and Shiogama

This was my first time taking an ANA domestic flight from Narita Airport. To arrive early and explore the airport, I decided to take the Keisei Skyliner paid express train. Nippori Station was very empty, and the train was even emptier, with less than 20% occupancy. Even so, Keisei Electric Railway had not reduced the frequency of trains. Upon arriving at the airport, the usually bustling train connection entrance was deserted. After all, most flights at Narita Airport are international, while domestic flights are mostly at Haneda Airport, and currently, international travel is being impacted far more severely than domestic travel in Japan.

Due to strong winds, I saw a notice before takeoff stating that the flight might return, so I was a bit apprehensive. However, the small propeller plane I was on managed to land safely in Sendai amidst severe turbulence. I had lunch directly at Sendai Airport and took the 11:40 long-distance bus straight to Matsushima. The journey took about an hour; there were only four passengers, and two got off along the way. Upon arriving in Matsushima, however, I found there were more tourists than I had anticipated. The parking lots were full of private cars, and there was a long line in front of the fish market next to the tourism center. Walking around, I felt something was off because I saw many staff members guiding tourists. In my experience, such a large deployment of manpower in Japan is usually to handle massive crowds. After all, Matsushima is one of the “Three Views of Japan,” and since this day was the Vernal Equinox Day holiday, one can imagine how lively Matsushima would have been on such days in the past. Because there were too many store touters and tourist service staff relative to the number of tourists, shop assistants actively solicited me wherever I went, which was quite annoying. I had never felt this way in Japan before; exaggerating a bit, it felt somewhat like being in Egypt. I walked along the seaside in Matsushima, looked at the Fukuura Bridge reconstructed with aid from Taiwan, and bought a sightseeing boat ticket for a trip to Shiogama a few hours later.

Next, I headed to Zuiganji, the most famous spot on the Matsushima coast. Zuiganji belongs to the Rinzai school and is a Zen temple; both the layout of the garan (temple complex) and the interior arrangements embody Zen principles. There are many caves around the temple, many of which contain Buddha statues carved from stone. Such caves are not common in Japan.

The main part of Zuiganji open for visiting is its “Hojo,” or main Buddha hall. The Hojo is a large hall containing multiple rooms separated by paper doors, with tatami mats covering the floors. The central room of the Hojo houses the Buddhist altar, while the paper doors of the other rooms feature paintings in different styles—some are gold-leaf Japanese paintings, others are Chinese Gongbi paintings, and there is one depicting “King Wen of Zhou Hunting.” I was somewhat confused by the presence of such a scene in a Buddhist hall; doesn’t Japanese Buddhism adhere to the precept of non-killing? Surrounding the building are several karesansui (dry landscape) gardens, the most distinctive art of Japanese Zen Buddhism. Zen emphasizes sudden enlightenment (satori), and viewing a dry landscape garden is said to bring a sense of peace and selflessness. It is even said that the iPhone was conceived through an epiphany while viewing a dry landscape garden (Source).

This was not my first time visiting a building named “Hojo” in a Japanese temple. I always had questions about it, so this time I finally researched the origin of the term. In Chinese, the modern meaning of “Fangzhang” (Hojo) is primarily the head of a temple, properly called a “Zhuchi” (Abbot). However, all temples can have an Abbot, but only the Abbots of larger temples are qualified to be called Fangzhang, so it is an honorific title. In Japan, Hojo more often refers to a building, usually the main hall. In fact, both usages are extended meanings derived through twists and turns; the original meaning is “one jo square” (approx. 3x3 meters), referring to a small space. The term originated from the “Vimalakirti Sutra”, which mentions that the layman Vimalakirti possessed great supernatural powers, and his small dwelling, the “Hojo Room,” could accommodate “high and broad thrones, heavenly beings, dragon kings, and spirit palaces,” which was deemed inconceivable. The Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei, whose courtesy name was Mojie, took his name from Vimalakirti (Weimojie). Initially, “Fangzhang” specifically referred to Vimalakirti’s room, later extending to mean a place that looks small but contains a universe within—i.e., the dwelling of a high monk. In China, “Fangzhang” shifted from referring to the dwelling of the Abbot to the Abbot himself. In Japan, “Hojo” generally shifted to refer to the main Buddha hall, although later, under the influence of Song and Yuan Dynasty China, “Hojo” in certain Japanese sects also came to refer to the Abbot himself.

Near the Zuiganji Hojo is Entsuin, where there is a mausoleum decorated in Western artistic style called Sankeiden. This hall was built in 1645 by Date Mitsumune, the daimyo of Sendai, as a mausoleum for his son who died young. The interior of Sankeiden comes from Europe, brought back by Hasekura Tsunenaga, a retainer of Date Masamune who was sent as an envoy to Europe. The interior features various Western decorations, including crosses and the hearts, spades, clubs, and diamonds from playing cards. The story of Hasekura Tsunenaga is legendary. He led a mission across the Pacific, traversed Mexico, then crossed the Atlantic to meet the King of Spain. During this time, he was baptized as a Catholic and even went to Rome to meet the Pope. He intended to establish diplomatic relations with Spain, but when he returned to Japan seven years later, he found that Japan had entered the era of isolation (Sakoku) and had begun persecuting Catholics. Although he achieved nothing diplomatically, he was recorded by Spain, France, and the Vatican under the name Faxikura (Hasekura). The end of the Sengoku period in Japan coincided with the peak of European global exploration, leading to many stories of encounters with the West. Japan attaches great importance to preserving historical sites from this aspect; Miura Anjin (William Adams), whose site I saw at the Tokaikan in Ito last time, is another example (Wandering in Japan: Kai and Izu).

After leaving Zuiganji, I walked back to the seaside for about ten minutes and crossed a connecting wooden bridge to Oshima, an island with stone carvings and temple ruins.

Around 3 PM, it was time to take the sightseeing boat to tour Matsushima Bay. On the way to the pier, I passed a construction site called “Matsushima Rikyu” (Matsushima Detached Palace), which I thought was related to the Imperial Family, but it is actually a new tourist facility under construction. The sightseeing boat I took departed from Matsushima, bound for Shiogama, passing numerous small islands covered with pine trees along the way.

To be honest, as one of the “Three Views of Japan,” the scenery at sea didn’t feel particularly special to me; viewing islands at sea is still best in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. With this, I have now seen all of the Three Views of Japan selected in the Edo period: Matsushima, Amanohashidate, and Aki Miyajima.

The fifty-minute sea tour ended when the boat arrived at its destination, Shiogama. The main attraction here is Shiogama Shrine, the Ichinomiya (supreme shrine) of Mutsu Province. The place name “Shiogama” is generally written as “塩釜” (e.g., for the train station and port names). Here, “塩” is the Japanese simplified character (Shinjitai) for “Salt” (鹽), and “釜” is a homophonous substitution (kama) for “Cauldron” (竈) which has a similar meaning. “Kama” (pot) and “Kamado” (stove/cauldron) do not mean the same thing, and it is not a relationship between new and old character forms, so for official local purposes, “塩竈” is still insisted upon; for instance, the government website clearly writes “Shiogama City” (塩竈市). As the most important shrine in Mutsu Province, Shiogama Shrine insists on using the orthodox character even for “Salt” (鹽). Additionally, “竈” also has a Japanese analogical simplified character (extended Shinjitai) written as “竃”, but it is not commonly used. It took over twenty minutes to walk from the port to Shiogama Shrine, which is located on a small hill. I entered from the “Back Sando” (approach) on the east and left via the “Front Sando” on the southwest. The main deity worshipped at the shrine is Shiotsuchi-no-Oji, one of the sea gods of Japan who protects navigational safety and is also the god of salt making. It is said to be beautiful here during the cherry blossom season, but I arrived a few weeks early and did not see large swathes of blooming cherry blossoms.

After finishing with Shiogama Shrine, I walked back to Hon-Shiogama Station and took the Senseki Line to Sendai to transfer, then returned to Sendai Airport. I could have taken the Tohoku Main Line from the other station, Shiogama Station, but the wind was too strong in the afternoon, and even the Tohoku Main Line trains had stopped running. There weren’t many people at Sendai Airport, but it wasn’t particularly scarce either; most domestic routes were still operating. Inside the airport terminal, there is a small aviation museum, mainly aimed at children, but there are also historical materials available to browse.

I had some cold soba noodles for dinner and continued flying to Osaka. I redeemed these two flight segments using United Airlines miles. Flying from Tokyo Narita to Osaka Itami, I insisted on finding a ticket that transferred in Sendai with a 9-hour layover, which only required 5,000 miles (valued at $70) and no other taxes or fees. Upon arriving at Osaka Itami Airport, I hopped directly onto the Osaka Monorail, going all the way to Kadoma-shi, where I stayed for the night.

Day 2: Kyoto Imperial Palace, Shokoku-ji, and Tsuruga

Waking up early in the morning, I ate the breakfast I had bought the previous night in my room. Many business hotels in Japan have microwaves and refrigerators in the rooms, which is very convenient. I went out and took the Keihan Electric Railway; the first stop was Iwashimizu Hachimangu. There is a cable car right next to the Keihan station, and it takes only three minutes to get up the mountain. Iwashimizu Hachimangu was once a typical “Shinbutsu-shugo” (syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism) temple-shrine complex. After the “Shinbutsu Bunri” (separation of Shinto and Buddhism) order during the Meiji Restoration, many Buddhist buildings here were destroyed. Descending from the shrine’s Front Sando, one can glimpse the grandeur of the past through the ruins of some temples along the way. At the foot of the mountain is the Tongu (temporary palace) of Iwashimizu Hachimangu.

Afterward, I continued taking the Keihan train one stop to Yodo. Not far outside the station lie the ruins of Yodo Castle. Built in the Edo period, Yodo Castle was a strategic point guarding the confluence of the Katsura River and Uji River. Now, only some stone walls remain of Yodo Castle. Inside the castle grounds, there is also a display board titled “Site of Tojin Ganji,” which legend says was the landing place for the Joseon missions to Japan. The “Tojin” here refers to Koreans.

Speaking of the concept of “Tojin” (Tang people), one should not interpret it literally. The Japanese did not simply call Chinese people “Tojin” (Karabito), nor did so-called “Karamono” (Tang things) necessarily come from China. The concept of “Kara” broadly refers to the mainland, including the Korean Peninsula. The kanji “Tang” (唐) is kun-read as “Kara,” which is likely derived from the ancient Korean kingdom of “Gaya” (Kara). Gaya, also known as Kaya, was located in the southeastern part of the Korean Peninsula and had a very complex historical relationship with Japan (see Mimana Nihon-fu), having always been a focal point of dispute between Japan and Korea.

Besides this, I have always found the term “Tojin-gai” (Chinatown) strange because, after the Tang Dynasty, almost no Chinese people referred to themselves as “Tang people,” unlike “Han people.” Conversely, historically, Japanese people would refer to people from the Chinese mainland (including the Korean Peninsula) as “Tojin”; for example, Nagasaki has the historic “Tojin Yashiki” (Chinese settlement). I therefore suspect that the term “Tojin-gai” is also an exonym, as in “Chinatowns” around the world, local Chinese usually call them “China City” or “Chinese Port/Town” (Huabu).

After seeing the Yodo Castle ruins, I returned to the station and took the Keihan train straight to Kyoto Jingu-Marutamachi, walking ten minutes from there to the Kyoto Imperial Palace. Before going to the Kyoto Imperial Palace, I passed by the “United Church of Christ in Japan Rakuyo Church” on the way. This “Rakuyo” (Luoyang) is an alias for Sakyo (eastern Kyoto), borrowing the name of “Luoyang, the Eastern Capital.” Ukyo (western Kyoto) was also called “Changan,” but Heian-kyo (Kyoto) declined on the Ukyo side due to drainage problems soon after it was built, so development concentrated in Sakyo. To this day, Kyoto is centered on Sakyo, so “Rakuyo” sometimes refers to the whole of Kyoto; currently, there are “Raku Buses,” “Rakuraku Trains,” and so on in Kyoto.

Next to the church, I encountered the specially opened “Former Residence of Niijima Jo,” the founder of Doshisha University. Afterward, I stopped by the nearby free Kyoto City Historical Museum, but the content was lackluster, so I left after a glance.

Although I have been to Kyoto several times, this was my first time stepping into the Kyoto Gyoen (National Garden). Kyoto Gyoen was the former imperial palace grounds; now mostly a park and open space, there are three places to visit: the Kyoto Imperial Palace, the Sento Imperial Palace, and the Kyoto State Guest House. The latter two require reservations, so I only visited the Kyoto Imperial Palace. The Kyoto Imperial Palace served as the imperial residence from the Nanboku-cho period until the capital moved to Tokyo, and it is still managed by the Imperial Household Agency. Historically, the Kyoto Imperial Palace has been burned down many times, but each time it was meticulously rebuilt according to its original appearance, so it retains certain characteristics of Heian period architecture. Every building within the Kyoto Imperial Palace has a unique history. The ones that left the deepest impression on me were the Shishinden and the corridors. The Shishinden is the largest hall in the Kyoto Imperial Palace; the plaza in front is covered with gravel, and the style of the surrounding red corridors is quite distinct from most existing Edo-period palaces in Japan, resembling instead the corridors of Shitennoji in Osaka and Horyuji in Nara.

Leaving Kyoto Gyoen through the north gate, I happened to encounter cherry blossoms in full bloom along the way, which attracted many people.

Outside the north gate is Shokoku-ji, a major temple of the Rinzai Zen sect, built by the Muromachi Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. Shokoku-ji is a major branch under the Rinzai sect; Kinkaku-ji and Ginkaku-ji in Kyoto are both “extra-mountain sub-temples” of Shokoku-ji. The Jotenkaku Museum inside Shokoku-ji is famous and exhibits many artifacts related to historical exchanges with China.

I found three items particularly interesting:

The first item is the “Imperial Edict of Ming Emperor Yongle,” which is the official document from the Yongle Emperor (Zhu Di) of the Ming Dynasty investing Ashikaga Yoshimitsu as “King of Japan.” It reads:

“You, King Minamoto no Dōgi, are loyal, wise, and love goodness. Above, you respectfully follow the Way of Heaven and serve the Court with reverence; below, you eliminate bandits and pacify the maritime realm. Your sincerity is known to Heaven and known to Us.”

Minamoto no Dōgi was the name Ashikaga Yoshimitsu used when requesting investiture from the Ming Dynasty. Previously, he had twice requested investiture under the name “Minamoto no Yoshimitsu” but was rejected. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s submission to the Ming Dynasty was driven by considerations of trade benefits and was primarily pushed by merchants from Fukuoka. This act of claiming vassalage to a foreign power was very likely to incite dissatisfaction among the daimyo and samurai loyal to the Emperor, so even as Seii Taishogun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu faced immense resistance. Chinese dynasties also never acknowledged the existence of an “Emperor” in Japan, only investing a “King of Japan.” Due to this delicate political atmosphere, at the investiture ceremony held at Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto in 1402, all attendees meeting the Ming envoys were Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s confidants; there were no royals, court nobles, or other samurai, strictly to keep a low profile. All in all, I was truly surprised to see the original edict here.

The second interesting artifact is the calligraphy “Song Yuan” (Song and Yuan Dynasties) by Lanxi Daolong. Lanxi Daolong was a high Rinzai monk who came to Japan from the Southern Song Dynasty in its final years and was the founding abbot of Kencho-ji in Kamakura. In 1274, 28 years after Lanxi Daolong arrived in Japan, Kublai Khan’s Yuan army invaded Japan from Goryeo. Lanxi Daolong was falsely accused of collaborating with the enemy and exiled to various places, one of which was Shuzenji in Izu (Wandering in Japan: Kai and Izu). Later, after being recalled, he wrote “Song Yuan,” piercing the impermanence of dynastic changes with a Zen narrative.

The third exhibit I liked was the painting of the Five Hundred Arhats by the Chinese painter Li Qifan, presented by Daxiangguo Temple in Kaifeng to Shokoku-ji in Kyoto. The painting is atmospheric and neat. The Dharma Hall of Shokoku-ji is very magnificent (though unfortunately, it was temporarily closed to visitors due to virus prevention). Looking at the Buddha hall that has stood for hundreds of years, and then thinking of the tumultuous past of Daxiangguo Temple in Kaifeng—not only destroyed by the Yellow River flood in the Chongzhen era of the Ming Dynasty but also having its remaining artifacts smashed by Feng Yuxiang—it makes one sigh endlessly.

After leaving Shokoku-ji, I took the subway Karasuma Line to Kyoto Station and bought a limited express ticket to Tsuruga. While waiting for the train, I randomly found a place that didn’t look crowded to eat. This eatery was called “Tsukumo,” read as tsukumo. One of the great interesting aspects of Japanese is this kind of jukujikun (special reading), where the reading is applied to the whole word rather than each character. Every jukujikun has a reason behind it, some being interesting historical stories, similar to idioms in Chinese. Another way to write tsukumo is “Tsukumogami” (Artifact Spirit), roughly meaning that if an object is left for a hundred years, it gains a spirit; missing one year makes it ninety-nine (tsukumo), though its true etymology awaits verification.

The Thunderbird limited express train from Kyoto to Kanazawa travels via the Kosei Line along the shores of Lake Biwa, then merges onto the Hokuriku Main Line, reaching Tsuruga in Fukui Prefecture in just one hour.

Tsuruga is home to the Echizen Province Ichinomiya, “Kehi Jingu.” Although most of it was rebuilt on ruins after World War II, it has existed here since the times of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, though later embellishments cannot be ruled out. Kehi Jingu is known as the general guardian of the Hokuriku region. Unlike Japanese Buddhist temples, the structure of shrines is generally simpler, and their history is dominated by vague legends, making it difficult to grasp their mysteries.

After visiting the shrine, I walked to the nearby Tsuruga City Museum. Although the museum is in the so-called city center and there is a shopping street with a covered roof, it was sparsely populated. Except for a few major metropolises, small towns across Japan all present this desolate scenery. Yet amidst the desolate streetscape, some local small shops persist in business; I really don’t know how they sustain themselves. The Tsuruga Museum was once the headquarters of Owada Bank, founded in the Meiji era. Bank architecture in Japan during that era was all in Western classical style. The museum exhibits the history of Tsuruga City, mainly focusing on the era after the Meiji Restoration.

Afterward, I continued to see the Tsuruga Port Station building by the sea. The railway line used to extend to the seaside where there was a station. The station is purely wooden, well-preserved, and has been converted into a free railway museum.

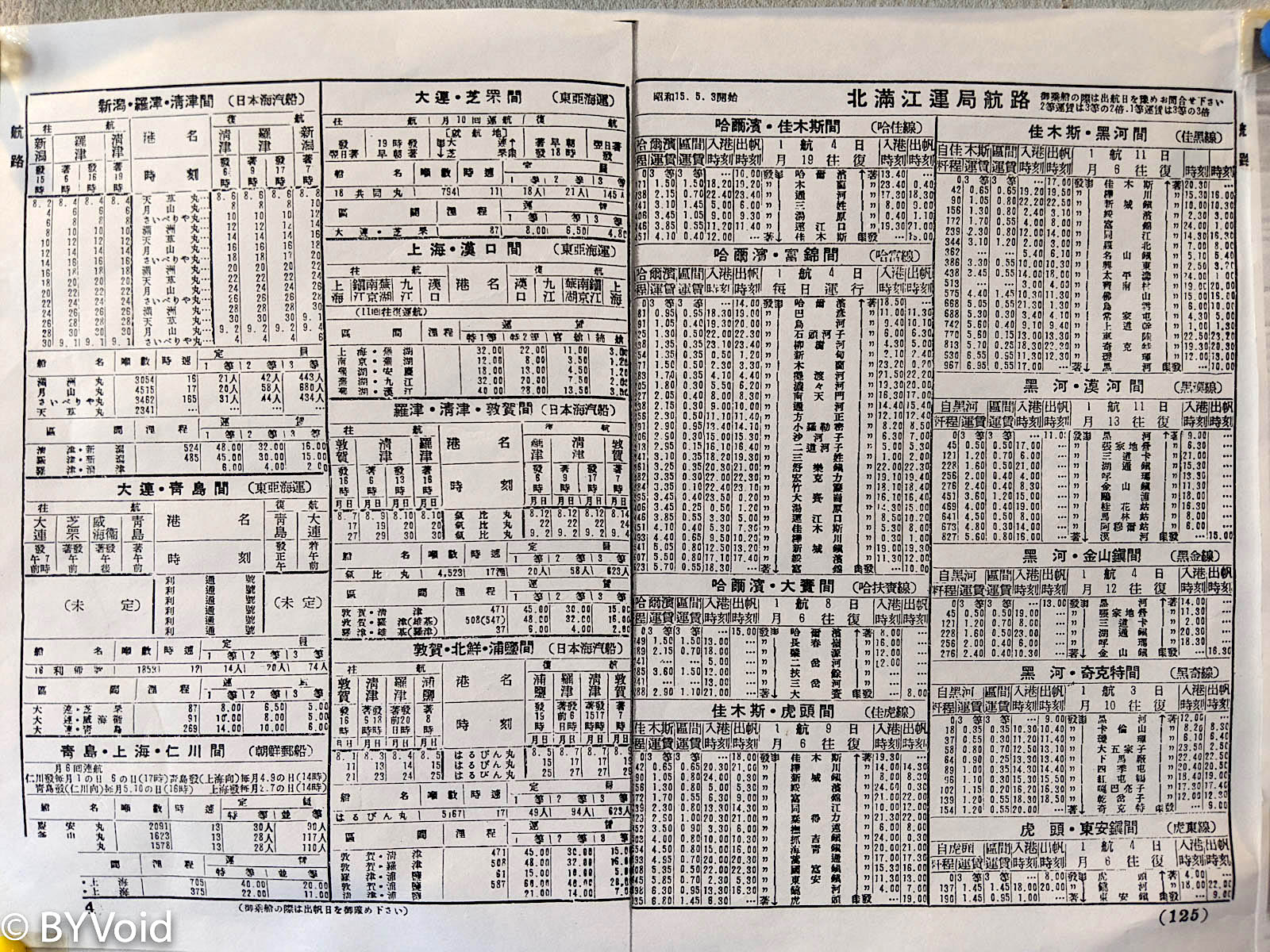

The museum content is very interesting, especially the special exhibit on the cross-sea route in the early Showa era. Departing from Tsuruga Port, one could go directly to Vladivostok (Urajiosutoku) in Russia, connecting to the Trans-Siberian Railway. The exhibits include Soviet advertisements from the 1920s stating that one could reach Europe in just 12 days, far faster than ocean liners of the time. Additionally, there were trains from Tokyo directly to North Korea, and even discount ticket sets like the “Korea-Manchuria-North China Circuit Ticket,” showing that the history of various rail passes in Japan is long-standing.

Near the old station building by the seaside is another museum called “Port of Humanity,” which unfortunately was also temporarily closed for epidemic prevention. The content roughly introduces the story of Jews fleeing from Russia to Japan during World War II, and Sugihara Chiune, the Imperial Japanese consul in Lithuania, issuing visas to thousands of people, similar to Ho Feng-Shan, the Chinese consul in Austria. If fate brings me back to Tsuruga, I’ll go in and take a look. Next to Tsuruga Port is another eye-catching building, the “Red Brick Warehouse,” converted into restaurants and souvenir shops. I have seen similar places in Yokohama, Hakodate, and Maizuru; the one in Tsuruga is a bit smaller.

It was getting late, and there were no buses nearby, so I had to walk for half an hour back to Tsuruga Station. From Tsuruga, I continued on the Hokuriku Main Line to Echizen-Takefu, then transferred to the Fukui Railway Fukubu Line streetcar. While waiting for the train, I bought food at the Heiwado supermarket; the prices were really cheap compared to Tokyo. I stayed the night in Fukui City.

Day 3: Fukui and Takaoka

The weather forecast said it would rain in the morning, but it was actually just cloudy. After breakfast, I headed to the Fukui Castle ruins. The Fukui Castle ruins are in the center of Fukui City near the train station and are now the site of the Fukui Prefectural Government Office. The ruins still retain stone walls, the inner moat (hori), the Yamazato-guchi Gate, and the tenshu base. Other buildings inside the castle are completely gone, and the wider outer moats have been filled in. You can climb up the tenshu base, offering a view of the moat and the western park.

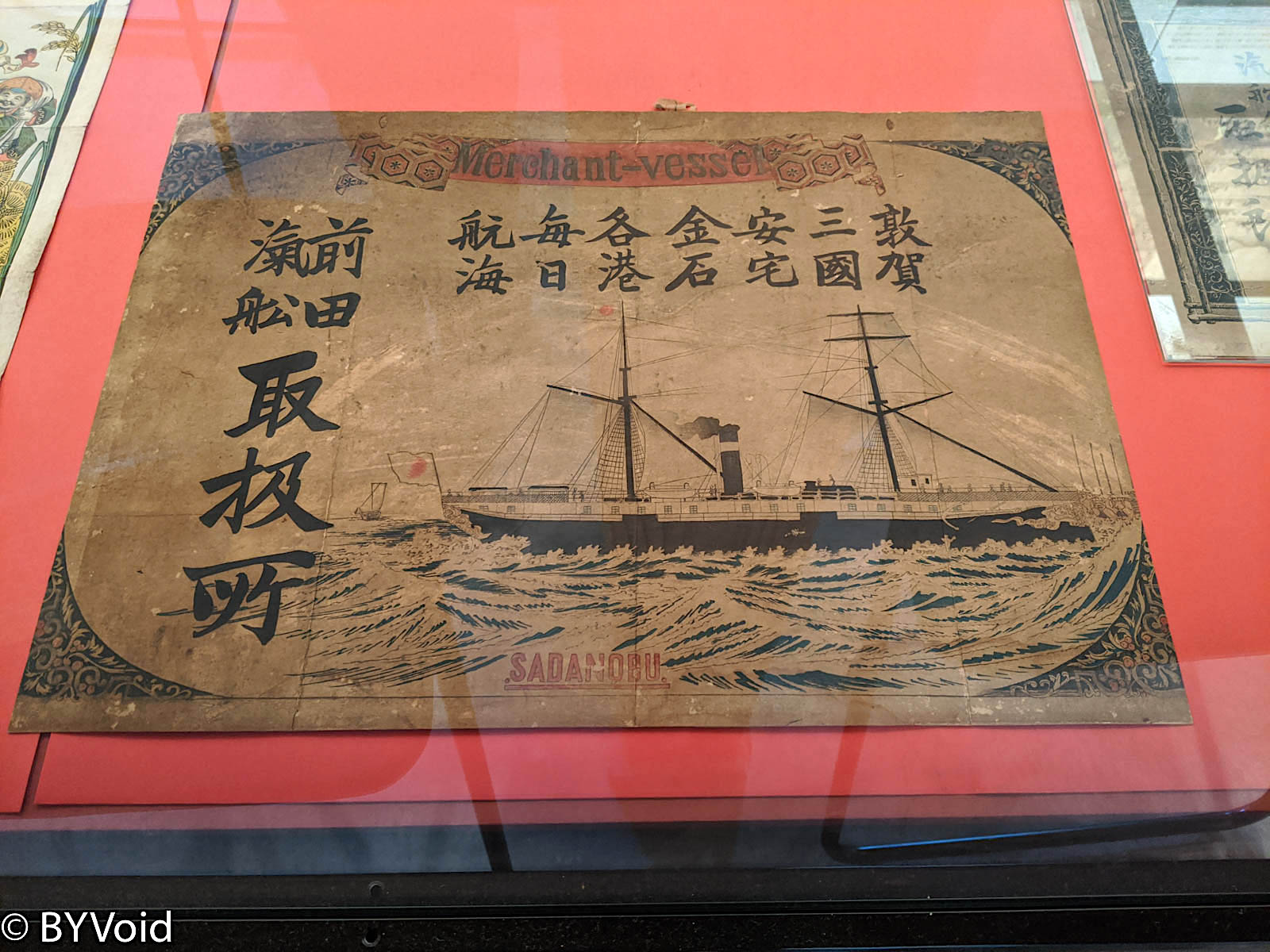

Afterward, I continued to Fukui Station and took the Echizen Railway to “Mikuni.” Along the way, I saw the yet-to-be-completed Kanazawa-to-Tsuruga section of the Hokuriku Shinkansen; the viaduct is under construction, expecting to open at the end of 2022. About fifty minutes later, I arrived at Mikuni, and the sky finally began to rain. Mikuni is a small town by the Sea of Japan, located at the mouth of the Kuzuryu River, and was once a port for “Kitamaebune” ships in the Edo period. The town is not big, but there is a Taisho-era bank, a European classical style building built by the Morita family, wealthy merchants who operated Kitamaebune locally. The bank is free to visit, and the architecture and decorations are well preserved. Kitamaebune were merchant ships of the Japanese Edo period that departed from Osaka, traveled through the Seto Inland Sea, and traded along the coast of the Sea of Japan. Now, many places along the Sea of Japan coast have relics of Kitamaebune. Kitamaebune utilized the seasonal Tsushima Current, departing from Osaka in March every year, going north along the Sea of Japan coast, reaching Hokkaido in late May, and starting the return journey when the current changed in late July, arriving back in Osaka in November. In an era when navigation technology was not yet developed enough, the route along the Sea of Japan was much safer than the route on the Pacific side.

The town also has the old residence of the local magnate Kishina family and a small archive museum. The staff were extremely enthusiastic, which was overwhelming. Visiting attractions and museums in Japan, what I fear most is encountering enthusiastic staff. Although I know they mean well and aren’t seeking anything from you—unlike the “enthusiastic” staff in tourist spots in Egypt or India—the problem is that I am not immediately recognized as a foreigner, yet my Japanese is not fluent enough for conversation. Enthusiastic staff usually explain things at a rapid speed, which makes me awkward. Sometimes I just pretend not to understand Japanese, but this also has side effects, as I often encounter “simplified” treatment that discounts the experience, just like the “simplified version” menus prepared for foreigners in many restaurants. One interesting detail mentioned in the history museum is that in 778 AD, Zhang Xianshou, an envoy from the Kingdom of Balhae (Bohai), crossed the sea and landed right here at Mikuni Port. Balhae and Japan had always been on good terms historically until Balhae was destroyed by the Liao. The relationship between Balhae and Japan is a very interesting piece of history, but since most of the coastal parts of Balhae are now within the Primorsky Krai of Russia and haven’t been excavated much archeologically, many historical mysteries remain to be uncovered.

After touring Mikuni, I planned to go to Tojinbo to see the spectacular seascape, said to be somewhat similar to the “Giant’s Causeway” in Northern Ireland. However, the weather was poor and the rain was getting heavier, so I went directly to Awara Onsen Station and took the Hokuriku Main Line limited express train further east. The zairaisen (conventional line) limited express train only goes to Kanazawa; further east, because the Shinkansen has been completed, the former Hokuriku Main Line ends there. The Hokuriku Main Line from Kanazawa to Naoetsu has not disappeared but is currently split into three sections operated by local entities. Surprisingly, I found quite a lot of people inside Kanazawa Station, with no gloomy atmosphere of a major epidemic. I had a quick lunch in Kanazawa, got on the IR Ishikawa Railway (split from the former Hokuriku Main Line) heading east, passed through Kurikara, where the train continued directly onto the Ainokaze Toyama Railway, and got off at Takaoka.

The first destination in Takaoka was Zuiryu-ji, a 15-minute walk south of the train station. Zuiryu-ji is a National Treasure temple, built by the Kaga Domain over three hundred years ago and now belonging to the Soto sect. The layout of the garan is said to be referenced from Jingshan Temple, one of the Five Mountains of the Southern Song Dynasty. The Buddha halls are on a symmetrical central axis, surrounded by corridors, with no pagoda, and there is a huge dry landscape garden on the periphery.

Next, I returned to Takaoka Station and took the Manyo Line tram for a few stops to the Takaoka Castle ruins. The trams in Takaoka are rare ultra-low-floor cars in Japan, hugging the ground, similar to those in many German cities. Takaoka Castle was built on a hill; now not much of the ruins remain, leaving only some stone walls. Inside the castle walls is the Etchu Province Ichinomiya, Imizu Shrine, with an endless stream of worshippers. The shrine has an attached wedding hall with gorgeous interior decorations.

After seeing the shrine, I walked to the nearby Takaoka City Museum, which has free admission. The exhibits mainly focus on local Takaoka history, plus some archeology, local folklore, and industry. Takaoka’s history is not very long, mainly developing after the Kaga Domain built the castle in the Edo period. Although the provincial capital of Etchu was here, there are only some archeological ruins now. In the few plain areas of Japan, except for the Kinki region, development was relatively late, mostly after the Edo period. This is because the ancient coastline of Japan was very different from now, and the alluvial plains at river mouths were prone to flooding, requiring high-level water conservancy engineering to turn coastal swamps into fertile fields.

The Lord of Kaga Domain, Maeda Toshinaga, named this place Takaoka, claiming it was taken from the poem “Juan A” in the Greater Odes of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing): “The phoenix sings, on that high ridge (Takaoka). The paulownia grows, facing that morning sun.” However, given that Takaoka is kun-read as “Takaoka,” I have reservations about this theory; it might be a forced interpretation. From the Edo period onwards, Japan introduced Confucianism, especially Neo-Confucianism, from China and the Korean Peninsula; before this, China’s cultural export to Japan mainly focused on Buddhism. In the Edo period, many daimyo families were well-read in the Four Books and Five Classics—Japanese samurai were not illiterate brutes—so the practice of attaching meanings from the Classic of Poetry to place names occurred. Even the Ritsuryo provinces established in the Asuka period were given Han-style names, such as calling “Omi Province” (Afumi no kuni) “Goshu” (Jiangzhou), “Iyo Province” (Iyo no kuni) “Yoshu” (Yuzhou), and “Nagato Province” (Nagato no kuni) “Choshu” (Changzhou). The map of Japan almost followed in the footsteps of Korea and Vietnam, becoming another “Little China.”

Coming out of the museum, I walked a short distance to the Takaoka Daibutsu (Great Buddha). This Great Buddha is cited along with the Great Buddha of Todaiji in Nara and the Great Buddha of Kamakura as the Three Great Buddhas of Japan. However, the Takaoka Great Buddha was burned down several times in history, and the existing bronze Great Buddha was recast in the early Showa period.

I walked back to the train station, passing through an almost empty shopping street. Countless small towns in Japan have declined to this extent; thinking about it makes one sigh. Opposite Takaoka Station are several bronze statues of Doraemon characters because this is the hometown of the author Fujiko F. Fujio. Takaoka actually also has a Fujiko F. Fujio Museum, but I didn’t have time to go this time.

From Takaoka Station, I continued to take the Ainokaze Toyama Railway, arriving in Toyama twenty minutes later. It was already dusk, so I didn’t tour Toyama this time. However, seeing that Toyama has a loop line tram, I took a ride around as a preview of Toyama.

After a simple dinner in Toyama, I continued east along the original Hokuriku Main Line. The Ainokaze Toyama Railway connects to Ichiburi Station in Niigata Prefecture, where it becomes the Nihonkai Hisui Line, running all the way to Naoetsu. I got off at Itoigawa and transferred to the Hokuriku Shinkansen to return to Tokyo.

The names of the three railways split from the former Hokuriku Main Line from Kanazawa to Naoetsu are truly laughable: “IR Ishikawa Railway,” “Ainokaze Toyama Railway,” and “Nihonkai Hisui Line.” The three perfectly embody the characteristic of Japanese “mixed writing.” The writing of each word is completely arbitrary, with no orthography to speak of (About Orthography). The place names “Ishikawa” and “Toyama” should have been written as “石川” and “富山”, the Chinese word “Ai” (Love) was deliberately written as “ai”, “Hisui” (Jade) was written as “hisui”, and of course, they didn’t forget the Latin letters “IR” and the loanword “Line”.

Update July 16, 2020: Upon verification, “Ainokaze” is the Hokuriku dialect for “Ayunokaze,” which uses the kun-reading kanji “East Wind” (東の風). Therefore, the “Ai” in “Ainokaze Toyama Railway” should not be written with the kanji “Love” (愛). If kanji were used, it should be “East,” yet various (unofficial) Chinese translations use “Love.”

Regarding the place name Itoigawa, since the Japanese simplified character is “糸魚川”, there is some controversy over how to translate it into Chinese. I support writing it as “絲” (Silk) because the orthodox character for Japanese “糸” has always been “絲”, including the on-reading shi and kun-reading ito. However, the entry in Chinese Wikipedia is “糸魚川”, similar to “Kinshicho” being “錦糸町” instead of “錦絲町”. If one blindly follows the literal “names follow the owner” rule, then the Chinese for “Yokohama” (橫濱) should also be changed to “橫浜”.

It was already night when I arrived at Itoigawa, and the station was almost empty. I changed here to the Shinkansen back to Tokyo. The three-day trip ended perfectly.

Last modified on 2020-07-15