Written in February 2021. Spring in Japan always arrives quietly; the temperature rises significantly all at once, and then before long, a cold wave strikes suddenly, returning everything to winter. My trip this time took place on just such a weekend. It was also from that day on that I started suffering from allergies for the first time in my life, and even now, I am still battling inexplicable allergies. Thinking back now to the days when I never had allergies, it truly feels like a lifetime ago. I dedicate this article to commemorating this watershed moment.

A Random Destination

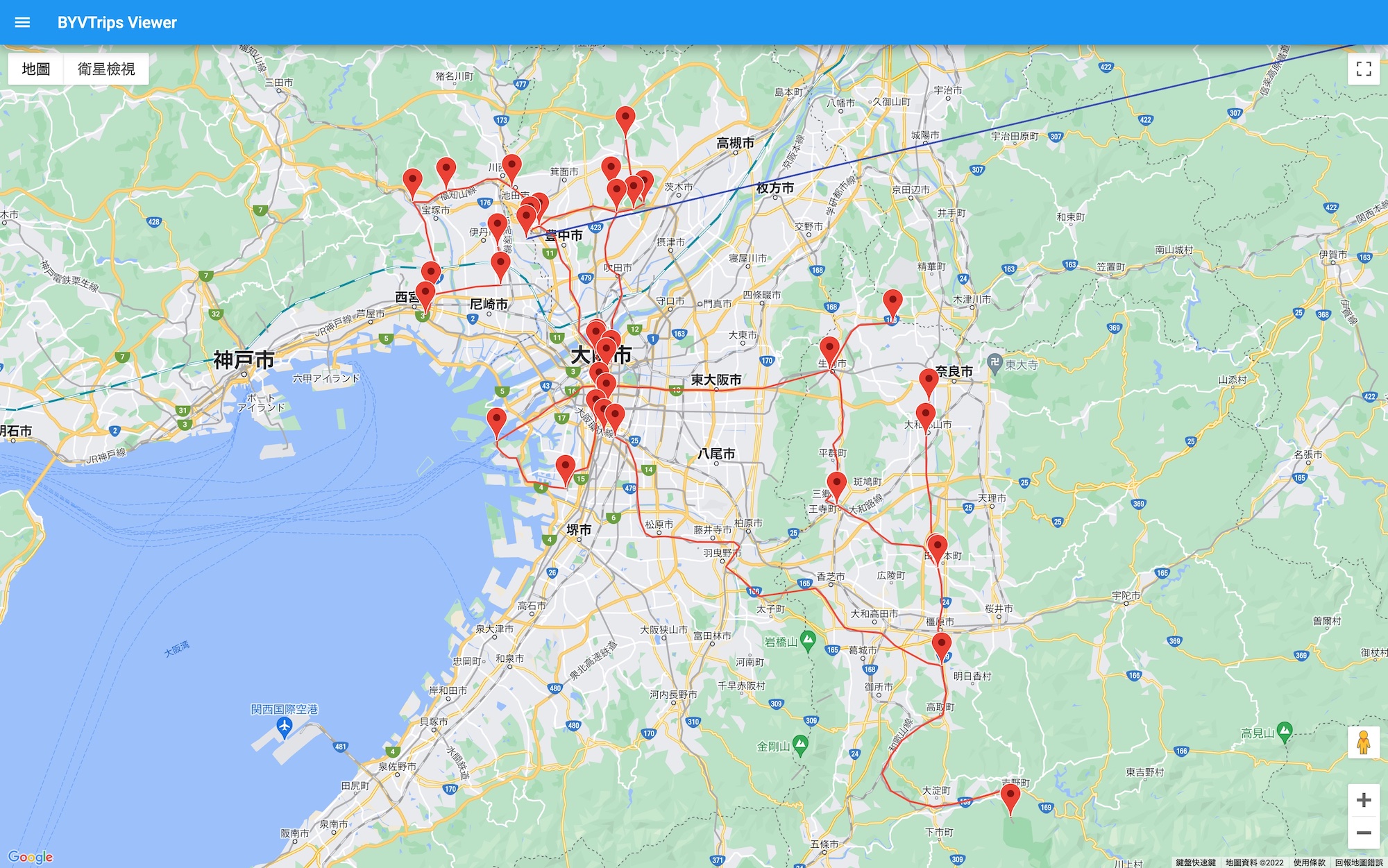

Since the beginning of 2021, I hadn’t left home for a long time and was getting a bit restless. As it happened, some Japan Airlines miles were about to expire, so I used Dokokani Mile (Where to Mile) to try my luck. “Dokokani Mile” is a special way to redeem miles on Japan Airlines; for just 6,000 points, you can get a round-trip ticket to a random destination. When booking, you first select the dates and time slots, and then four possible locations appear. After paying the miles and waiting a few days, Japan Airlines reveals the destination. According to Murphy’s Law, the selected destination is often the one you least want to go to. This time was an exception; my randomly selected destination was Osaka. I don’t know how many times I’ve been to Osaka, but I look forward to it every time I finish a trip there. After all, with Osaka as the hub, Kansai is the center of Japanese history and culture, with countless places to visit.

Dotonbori Without Tourists

After arriving at Osaka Itami Airport on Friday night, I first went to the Shinsaibashi (心齋橋) and Dotonbori (道頓堀) area. I didn’t have a specific destination; I just wanted to see how the streets, once occupied by tourists from all over the world, looked now. Sure enough, the Shinsaibashi shopping arcade was very empty, many shops had closed down, and the words “Tax Free” on huge signboards were broken. Dotonbori was much the same; a few shops were still operating bleakly, despite the scarcity of customers.

That night I stayed at the grand bathhouse in Shinsekai (新世界), which has dedicated guest rooms. This bathhouse is the largest I have visited in Japan, featuring bathing styles from various countries. It is the bathhouse I recommend most; it is worth a try for anyone coming to Osaka.

Kinpusen-ji

The next morning, I walked from the Shinsekai bathhouse to Kintetsu Abenobashi (阿部野橋) Station and took the limited express train to Yoshino (吉野). Yoshino is located south of Nara City, somewhat distant from Osaka; the direct train takes 1 hour and 15 minutes.

Yoshino is very famous during the cherry blossom season, but coming in this season, I obviously wasn’t there for the flowers, but to visit the famous Kinpusen-ji (金峯山寺). Kinpusen-ji is located in the Yoshino River (Kinokawa) valley at the southernmost edge of the Nara Basin. Further south lie the rugged mountains of Kumano.

Kinpusen-ji is a representative of Japanese Shinbutsu-shugo (syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism). The principal deity worshipped is Zao Gongen (藏王權現). Zao Gongen does not come from Indian or Chinese Buddhism but is an object of faith born from Japanese indigenous Buddhism. The term Gongen refers to the manifestation of a Buddha (in Mahayana Buddhism). After the concept of Gongen was introduced to Japan, it was localized, implying that the Yaoyorozu no Kami (Eight Million Gods) of Shinto are all manifestations of various Buddhas. This theory is known as Honji Suijaku (本地垂蹟). For example, the Honji Suijaku theory holds that Amaterasu (天照大神) is the manifestation of Dainichi Nyorai (大日如來, Mahavairocana). After the Meiji Restoration, out of nationalism, the Honji Suijaku theory was thoroughly denied by the new government. With the promulgation of the “Kami and Buddhas Separation Order” (Shinbutsu Hanzenrei), Buddhism suffered unprecedented suppression, to the extent that syncretic temples are now rare.

Visiting Buddhist temples in Japan, compared to China, often feels “purer”. By pure, I mean the deities and bodhisattvas enshrined in the temples are all from Mahayana Buddhism (of course, Mahayana, especially Esoteric Buddhism itself, mixed in quite a few Brahmanic or even Zoroastrian gods, but that’s another topic). In many temples in China, one often encounters gods from Taoism and traditional Chinese folk beliefs mixed in, such as Guan Yu, the God of Wealth, and Mazu. This is precisely the result of Japan’s separation of Shinto and Buddhism over a hundred years ago, making Japanese Buddhism more “fundamentalist”. Of course, there are many exceptions, and Kinpusen-ji, which I visited today, retains a large amount of syncretic elements.

Coming out of Yoshino Station, there is still quite a hike up the mountain, but there is a ropeway available. The ropeway takes only 3 minutes to reach the mountainside; to reach Kinpusen-ji, you still have to walk a bit. The first thing you see is the Kuromon (Black Gate), which is the first mountain gate.

Continuing for ten minutes, you reach the second mountain gate, named Hosshinmon (發心門). Although it is called Hosshinmon (Gate of Awakening to Faith), it is clearly a copper Torii (鳥居). The Torii is an important structure in Shinto; according to Shinto, passing through a Torii means entering the divine realm. Being both a Torii and a mountain gate shows that gods and Buddhas are one entity here, not yet separated.

The final gate is the most spectacular Niomon (仁王門). The Niomon was under repair and could not be viewed up close, but its magnificent aura could be felt from a distance.

Bypassing the Niomon, you enter the main area of Kinpusen-ji. The main building of Kinpusen is a huge Buddha hall named “Zao-do” (藏王堂). Zao-do is very majestic, featuring a double-eaved hip-and-gable roof (Mokoshi-tsuki Irimoya-zukuri), and the roof material is Japan’s unique cypress bark (Hiwadabuki). Zao-do enshrines the principal deity Zao Gongen, but it is not usually shown to the public. The principal Buddha is only unveiled for worship on special days (Gokaicho). This is also one of the characteristics of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, mainly found in temples of the Shingon and Tendai sects, though exoteric sects like Jodo and Zen occasionally have “Secret Buddhas” (Hibutsu) as well. Entering the hall, you can see other Buddhas surrounding the area, including a statue of Zao Gongen. The statue glares with wide-open eyes, resembling Fudo Myoo (Acala). Aside from this, there are not many traces of Shinto left inside the great hall.

The Zao Gongen enshrined at Kinpusen-ji is the principal deity of Japanese Shugendo (修驗道), appearing in the form of a Wisdom King (Myoo). Shugendo is an ancient tradition of mountain asceticism inherited from Buddhism, also known as Aranya (forest) practice. The original meaning of Aranya is forest, which later extended to mean a temple, so some temples or practice grounds are also called “jungles” (Conglin).

In the Nara period, the ascetic En no Ozunu (役小角), while practicing at Kinpusen-ji, founded Shugendo inspired by the manifestation of “Zao Gongen,” a fusion of Shakyamuni Buddha, Avalokitesvara (Kannon), and Maitreya (Miroku). Shugendo later merged into Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, deeply influenced by the Shingon and Tendai sects. To this day, the Kumano mountains in southern Nara remain a training ground for Shugendo. Shugendo can be described as the most localized branch of Buddhism in Japan.

The Yoshino Court

Not far below the terrace where Zao-do stands is the “Yoshino Imperial Palace Site,” where a three-story octagonal pagoda named “Nancho Myohoden” (Southern Court Myoho Hall) stands. According to the information board, this was once the site of the Southern Court’s Imperial Palace, where Emperor Go-Daigo (後醍醐天皇) of the Nanboku-cho period (Northern and Southern Courts period) based himself to oppose the Northern Court controlled by the Ashikaga Shogunate.

Yoshino has historically been the location of imperial villas, but its highlight moment was at the end of the Kamakura period. At that time, Emperor Go-Daigo fled Heian-kyo (Kyoto) carrying the “Three Sacred Treasures” symbolizing Yamato sovereignty and divine right, exiled himself to the Yoshino palace, and established the Southern Court to stand against the Ashikaga Shogunate’s Northern Court, initiating the half-century-long Nanboku-cho period. Because the base was in Yoshino, the Southern Court is also called the Yoshino Court. The distance from Yoshino to Kyoto is actually less than 100 kilometers, which cannot be compared to the Northern and Southern Dynasties in China at all. Using China as a reference, it is truly inconceivable that the small Kinai plain could accommodate two courts confronting each other for fifty-seven years. Even after the fall of the Southern Court, its remnants (the Later Southern Court) continued to resist the shogunate until the Sengoku period in the late 15th century. However, during the Meiji Emperor’s reign, history was revised, and the Southern Court was finally designated as legitimate.

Walking south from Kinpusen-ji for a few minutes, you reach another legendary imperial palace, now named Yoshimizu Shrine (吉水神社). This unassuming shrine has a shoin (study hall) with a significant background. According to its explanation, the Yoshimizu Shrine Shoin was originally Yoshimizu-in, a monk’s quarter of Kinpusen-ji, which was converted into a shrine after the separation of Shinto and Buddhism. Yoshimizu-in claims to be the oldest shoin in Japan, dating back to the Hakuho period (7th century). However, I am skeptical of this claim because, according to scientific verification (dendrochronology), the East Pagoda of Yakushi-ji in Nara is the only existing building from the Hakuho period.

The Yoshimizu Shrine brochure also states that Minamoto no Yoshitsune (源義經) and his beloved mistress Shizuka Gozen (靜御前) hid at Yoshimizu-in during the late Heian period. Later, Emperor Go-Daigo also used this place as a palace, and this building is the only existing palace of the Southern Court. Later in the Sengoku period, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豐臣秀吉) held a flower-viewing banquet in Yoshino and stayed at Yoshimizu-in for several days. The exhibits in Yoshimizu Shrine include various rare treasures, such as Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s bronze bell (dotaku) and gold folding screen, Emperor Go-Daigo’s biwa (lute), Ikkyu’s calligraphy, and a letter from Tokugawa Mitsukuni of Mito. Because it is so exaggerated, I hardly dare to believe it is true; it feels like there might be some forced associations.

After leaving Yoshimizu Shrine, I went down the mountain the way I came. Although there are other shrines and temples deeper in the mountains, and the Miyataki ruins at the foot of the mountain (said to be an imperial palace from the Asuka period), I did not visit the other palace sites of the Yoshino Court this time due to inconvenient transportation.

Koriyama Castle

I took the Kintetsu train back to Kashiharajingu-mae, and next, I had to transfer to the Kintetsu Kashihara Line to go to Koriyama. During the transfer, I spent ten minutes quickly finishing lunch inside the station. Many stations in Japan have small cafeterias inside, which are very suitable for a quick meal.

Getting off at Kintetsu Koriyama Station and walking for 10 minutes, I arrived at Koriyama Castle (郡山城). Koriyama Castle is not particularly famous, but in the Kinki region (Kansai), Japanese-style castles are relatively rare. This is because Kinki was not the sphere of influence of Daimyos (feudal lords) but was always directly ruled by the “Court,” similar to the royal domain of Luoyi in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. In 1580, Tsutsui Junkei built a castle here. This was the only castle in Yamato Province at the time. As the direct sphere of influence of the Emperor and court nobles, it was only when they declined to insignificance that they could tolerate feudal lords (warrior families) building castles here. Not much of Koriyama Castle remains, only a reconstructed gate, a moat, and the tenshudai (keep base). Climbing the tenshudai, you can overlook the surrounding plains.

Koriyama Castle and its surroundings are now a park. I happened to encounter plum blossoms in full bloom; the scenery was enchanting.

Osaka Port

After admiring the plum blossoms at Koriyama Castle, half the afternoon had passed. I started to return to Osaka, taking the opportunity to ride railway lines I hadn’t used before. I took the Kintetsu Kashihara Line to Tawaramoto (田原本), then sprinted out of the station to Nishi-Tawaramoto (西田原本) about a hundred meters away. Although both stations belong to Kintetsu Railway, they are not connected. Even worse, the transfer time was only three minutes; otherwise, I would have to wait an extra half hour. I don’t know why the timetable is arranged like this; maybe almost no one transfers here.

I got on the train departing from Nishi-Tawaramoto, and in just over twenty minutes, I reached the terminus, Shin-Oji Station. Walking two hundred meters from the Shin-Oji exit is another Kintetsu station, Oji, which is also unconnected, and the transfer time was only four minutes—impossible without running. After catching the train, I could finally rest. After transferring again at Ikoma, I rode all the way to the terminus at Osaka Port, Cosmo Square (コスモスクエア). This is a place built on reclaimed land, with a scenic seaside park and many high-rise residential buildings nearby. Departing from the same station, there is an automated guideway transit (AGT) line, which is particularly suitable for sightseeing. The style here is very similar to Odaiba in Tokyo.

The name “Cosmo Square” is very characteristic of its era; names of this style were common during Japan’s bubble era at the end of the Showa period. At that time, the Japanese people’s confidence was sky-high, as if the Earth could no longer contain Japan, leaving only the exploration of the cosmos and the future.

Before sunset, I arrived at Suminoekoen Station. There is an Osaka Gokoku Shrine (大阪護國神社) here. Gokoku Shrine basically means Yasukuni Shrine, except only the head shrine in Tokyo can be called “Yasukuni” (Peaceful Country), while others are “Gokoku” (Protecting the Country). Cities large and small across Japan have a Gokoku Shrine; these are remnants of pre-war State Shinto, places to summon the spirits of and memorialize soldiers who died before the defeat of the Empire.

The most prominent features of Gokoku Shrines are their huge bronze or stone Torii gates and various cenotaphs (memorial monuments).

The cenotaphs come in all shapes and sizes, some shaped like artillery shells, and there is even a “Monument to Beloved Horses,” truly a living fossil of militarism.

Osaka Expo Commemorative Park

Early the next morning, I left my accommodation and headed straight for the Expo Commemorative Park in northern Osaka. Osaka hosted the World Expo in 1970, known in Japan as the “Bankoku Hakurankai” (Expo of Ten Thousand Countries), and the venue has been preserved to this day as the Expo Commemorative Park. The park is enormous; you could spend a whole day there. I entered from the East Gate early in the morning and walked for a long time before reaching the central area. The park still retains the landmark Tower of the Sun (太陽之塔) from that time; it is still a popular photo spot, and the busiest place in the park.

Steel Pavilion Museum

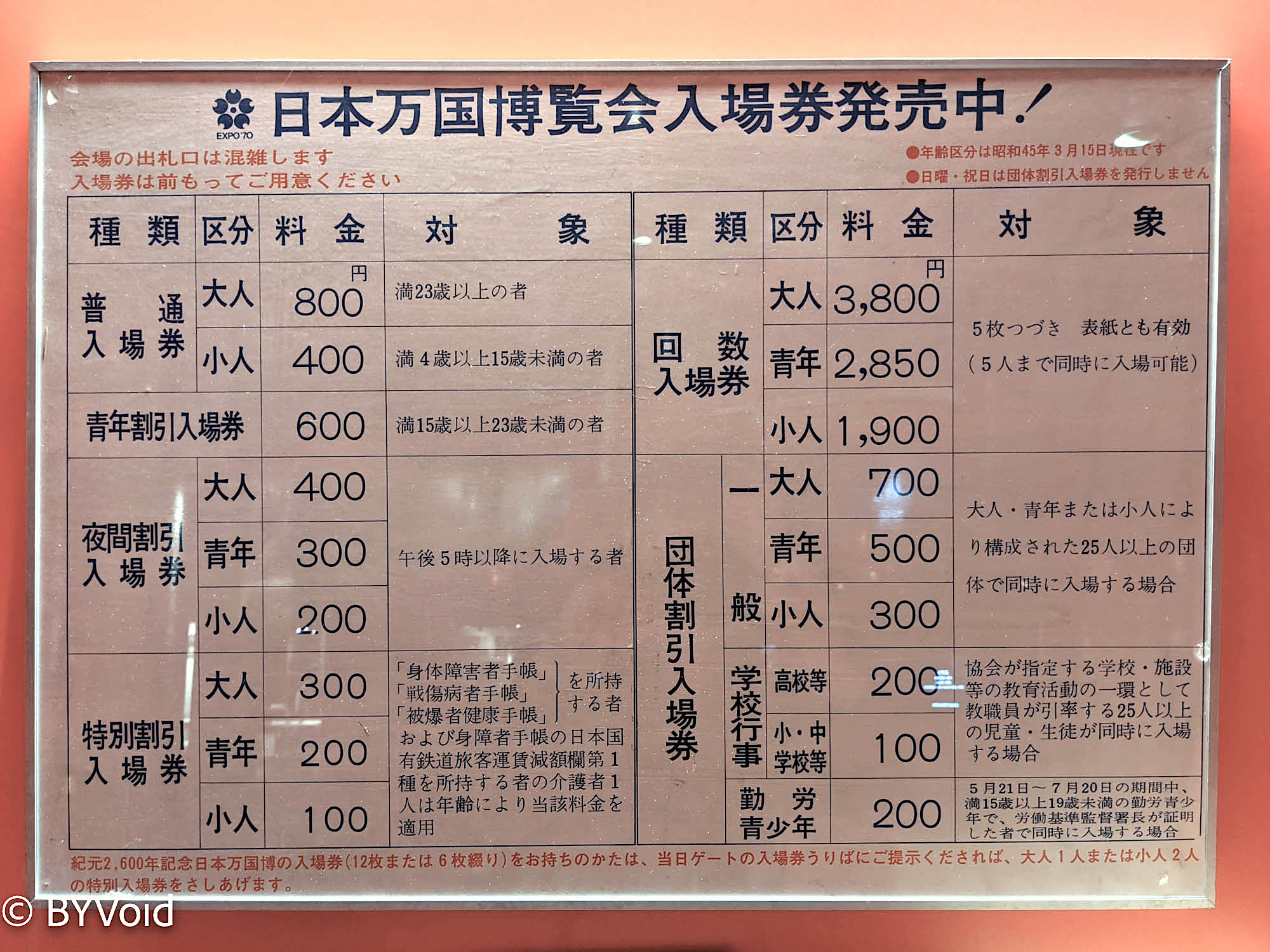

This huge park was once crowded with pavilions from countries all over the world, but now they have all been demolished, leaving only the Steel Pavilion, which is used as the Expo ‘70 Pavilion museum to commemorate that unprecedented gathering in 1970. Paying to enter the museum, I found it unexpectedly good. The museum has numerous exhibits, almost all items intentionally preserved from that time, such as admission tickets, display boards, and advertisements from back then. There are also some very interesting statistics, such as 48,139 lost children in the venue, 55 weddings, 1 birth, 2,755 toilet stalls, etc.

As one of the two major events of Japan’s economic boom era, the Osaka Expo, like the Tokyo Olympics, created much history. For example, it was the first World Expo where the organizer made a profit. Among the hundreds of pavilions from 77 participating countries, the tallest and most popular building was the Soviet Union Pavilion; 1970 happened to be when the Soviet Union was at its peak in that era.

Osaka is about to host the World Expo again in 2025. After the fiasco of the Tokyo Olympics, I’m afraid no one believes this Expo can recreate the glory of the past. The two successful events half a century ago were not the cause of stimulating Japan’s economic development, but rather the result of that booming era. Now Japanese society is permeated with a sense of failure; unless people’s confidence can be reversed, I fear this will leave the Japanese economy bleak for a long time.

Japanese Garden

The Japanese Garden in the northern part of the park has also been preserved, but I was somewhat disappointed after visiting it. This garden might be nice for someone who hasn’t seen many Japanese gardens because it has a little bit of every style of garden element, but nothing stands out. However, it separates gardens of different Japanese eras; perhaps it’s not bad if viewed as a history museum of gardens.

National Museum of Ethnology

Another highlight within the park is the National Museum of Ethnology. I initially thought it might be a Japanese folklore museum or a museum of the Japanese people, but I was surprised to find it contains various different cultures and peoples from around the world. The exhibition halls are arranged by continent. For each ethnic group, various cultures and customs are covered. The exhibits are carefully selected, distinctive yet unconventional, and of a very high standard. Another commendable point is that it keeps pace with the times, with a section specifically displaying immigrant groups in Japan in recent years.

Nakayama Kannon

Starting in the afternoon, I suddenly developed symptoms of allergic rhinitis. Suspecting it was caused by pollen in the Expo Park, I left quickly.

I took the Hankyu Line to Nakayama-kannon Station in Takarazuka City to visit Nakayamadera (中山寺). Nakayamadera belongs to the Shingon sect, follows Esoteric Buddhism, and its principal deity is the Eleven-faced Kannon. The principal Kannon is a “Secret Buddha” and is not usually open to the public. Nakayamadera claims to be a Kannon sacred site established by Prince Shotoku, but the existing buildings can only be traced back to the Sengoku period.

There are many sub-temples within Nakayamadera, each enshrining different Buddhas of the ten directions and heavenly bodhisattvas. Among them is “Seiju-in” (Achievement Hall), which enshrines Kokuzo Bosatsu (Akasagarbha Bodhisattva). Kokuzo is one of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas of Mahayana Buddhism, in charge of the Great Elements (mahābhūta) and the Void Realm (ākāśa-dhātu). Praying to Kokuzo Bosatsu can grant boundless memory, which is very suitable for East Asian-style exams. Compared to praying to Manjushri (Monju), who represents great wisdom, praying to Kokuzo Bosatsu is straightforward. If one truly obtained great wisdom from Manjushri, one might just see through the hyper-competitive nature of exams without actually helping with the exam itself. It’s better to pray to Kokuzo Bosatsu to directly gain infinite memory, delivering a strike from a higher dimension against the exam. Nakayamadera understands this well, writing “Pass Entrance Exam” and “Academic Achievement” on Kokuzo Bosatsu’s signboards.

There is a blue five-story pagoda in Nakayamadera with a unique style. Because of its color, it is named “Seiryuto” (Blue Dragon Pagoda). Although one cannot enter this pagoda, one can understand the internal mandala from the outside. Inside the pagoda are the Five Wisdom Buddhas of the Diamond Realm (Vajradhatu), with Mahavairocana Buddha (Dainichi Nyorai) in the center, Akshobhya in the East, Amitabha in the West, Ratnasambhava in the South, and Amoghasiddhi in the North.

From a close distance, the color of this five-story pagoda is particularly vivid, with very high contrast; looking at it for too long can even make your eyes uncomfortable.

In the afternoon, my allergic rhinitis began to worsen, so I had to end the trip and return to Tokyo. Unexpectedly, allergic rhinitis would accompany me from then on.

Last modified on 2022-05-13