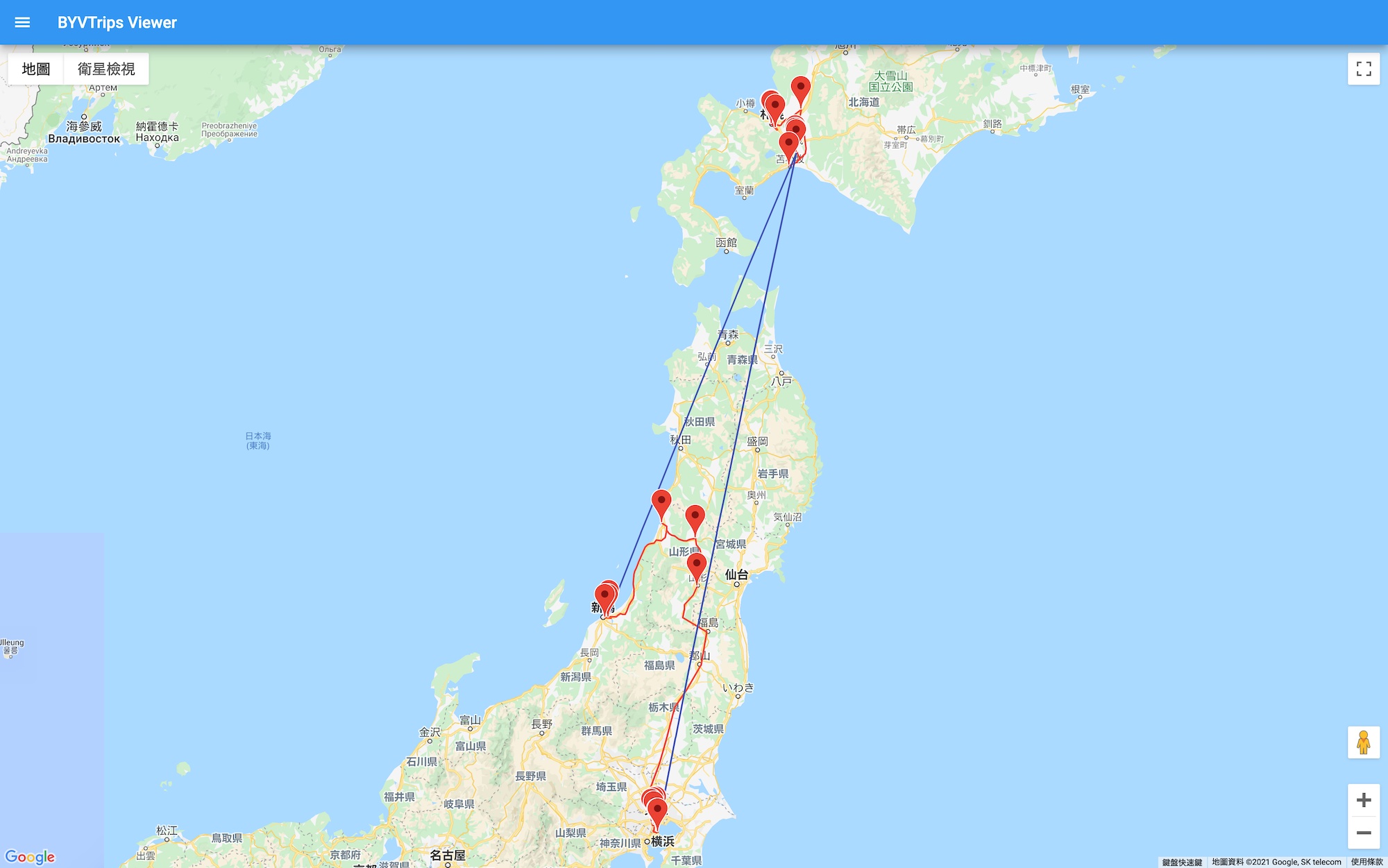

Time rewinds to late August 2020. I arrived in Hokkaido again, even though I had just visited once in early July. This time, I was merely passing through Hokkaido; or to be precise, I was specifically “passing through.” This was because I had spent another 5,500 United Airlines miles to redeem a ticket from Tokyo Haneda to Sapporo and then to Niigata. The departure time was Saturday morning from Tokyo to Sapporo, and then from Sapporo to Niigata in the evening. By using this method, I could travel across Japan at the lowest possible cost.

A Not-So-Smooth Departure

Although I had set my alarm for 6:30, I suddenly woke up at 6:20 on Saturday morning. I don’t know why, but I often wake up abruptly a few minutes before my set alarm goes off. As long as I set an alarm, I will wake up even if it doesn’t ring, but if I forget to set it, I will truly oversleep. I find this phenomenon hard to explain.

I originally planned to take the direct bus from Shibuya (澀谷) to Haneda Airport, but after stepping out, I suddenly felt like it had been a while since I took the Yamanote Line, so I changed my mind and went to the train station. The area around Shibuya Station is undergoing the largest “redevelopment project” in its history, so the station’s structure changes every so often. Because I accidentally went to the wrong platform at Shibuya Station, I missed a train and didn’t arrive at the airport until 7:45 AM. The first leg of the flight was with Air Do. Air Do does not have its own check-in counters but is handled by All Nippon Airways (ANA). I entered my ticket number at the ANA self-check-in kiosk but found no information, so I had to go to the manned counter. The counter staff also checked for a long time and even called a supervisor before finally managing to print the boarding pass. It seems very few people redeem Air Do flights using foreign airline mileage, so their automatic ticketing system cannot handle it smoothly. By this time, there were less than fifteen minutes left until takeoff, but taking domestic flights in Japan is generally not an issue, especially with the significant decrease in travelers. I quickly walked to the boarding gate and finally successfully boarded an old Boeing 767; the interior decoration looked like a style from twenty years ago. Such old planes are rare in Japan now, so encountering one to experience it was lucky. Unfortunately, the good times didn’t last. The plane began to taxi, and just as I was preparing to rest, the captain’s voice came over the broadcast apologizing. Although the Japanese was spoken very quickly and I didn’t completely understand it, I sensed the situation might be bad. Sure enough, a few minutes later, the plane returned to the boarding gate. This time the flight attendant made an announcement, and I finally understood that it was a mechanical failure and the flight was canceled.

Back at the boarding gate, hundreds of people formed a long line waiting to rebook. I fell to the end of the line. Realizing I couldn’t just wait idly—otherwise, I didn’t know if there would be any tickets left for today by the time it was my turn—I picked up my phone and called United Airlines directly. In recent months, United’s customer service line has been particularly easy to get through, likely due to fewer passengers, and the customer service team seems not to have undergone massive layoffs. The United agent initially said they didn’t see the flight cancellation information in the system, but they still readily rebooked me on the earliest next ANA flight, taking off in half an hour at 10:00 AM. However, the United agent told me I still had to print the boarding pass at the airport, so I had to continue queuing. By the time it was my turn, it was already 9:45, but the staff said I could only be rebooked on the 10:45 flight. I firmly disagreed, and although they kept apologizing verbally, it was of no use. Even though the people ahead of me in line had all rebooked for the 10:45 flight, I insisted that United had already rebooked me. Seeing my firm attitude, the ground staff took me directly to the gate for the 10:00 departure, where the ANA staff quickly printed my boarding pass. My experience with service industry personnel in Japan who apologize profusely but don’t solve the problem is to be firm, argue on reasonable grounds, yet remain polite; this way, you won’t be easily fobbed off.

Muroran Main Line

The plane arrived at New Chitose Airport (新千歲機場) at 11:30, two hours later than scheduled. Since my next flight to Niigata was at 7:30 PM, I decided to change my route and take a train halfway around Sapporo. The route was: from New Chitose Airport to Minami-Chitose, transfer to the Chitose Line to Tomakomai (苫小牧), then transfer to the Muroran Main Line (室蘭本線) to Iwamizawa (巖見澤), and finally transfer to the Hakodate Main Line (函館本線) back to Sapporo. Taking the Muroran Main Line train from Tomakomai to Iwamizawa was my main objective because this section of the railway is already on the list of high-risk lines for abolition. Given the high maintenance costs and low passenger numbers, JR Hokkaido is likely to announce the abolition of this section in the future. Although officially abolishing a section of railway requires a long consultation process, if an earthquake or flood disaster occurs one day, JR Hokkaido can “suspend operations indefinitely” and then choose a time to permanently abolish it later. Just like the Hidaka Main Line (日高本線), which was officially abolished in 2021, it had actually been suspended due to a disaster since 2015.

The railway line from Tomakomai to Iwamizawa runs through plains, with boundless fields on both sides of the train windows. Such scenery is completely different from the three main islands of Japan (Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu). In the few plain areas on the mainland, the population density is very high, almost entirely towns, and fields only appear in patches in mountain valleys. The scenery of fields in the valleys is also beautiful, but it feels very different from the endless expanse of Hokkaido. Of course, compared to the field scenery of the American Midwest or Ukraine, Hokkaido is still not quite as grand.

On the way, I encountered a station named “Hayakita” (早來 - literally “come early”). Does this mean one should come to see it early, otherwise, it won’t be seen after the line is abolished?

The train on this section of the Muroran Main Line had only one car, but surprisingly, it was quite full. Several passengers were carrying cameras and tripods, appearing to be there for the experience just like me. The train did not travel slowly, but there were many stops along the way, taking an hour and a half for a journey of less than one hundred kilometers. Many of the intermediate stations did not look small, suggesting that quite a few people must have used them in the past. Japan is truly facing a severe problem of population outflow everywhere except Tokyo and Okinawa. It is predicted that after 2025, even Tokyo will begin to see a population decline, leaving only Okinawa. When the Ryukyu King Sho Tai (尚泰) saw his kingdom destroyed, he probably never dreamed that Japan would see such a day.

Cool Sapporo

Iwamizawa is considered a satellite city of Sapporo, and one can tell from the station facilities that there are quite a few people during commute times. I didn’t stay long in Iwamizawa and switched to the Hakodate Main Line to return to Sapporo. The scenery on this section of the railway from Iwamizawa to Sapporo was also nice, but there were significantly more people. Although I have been to Hokkaido many times, this was only my second time entering downtown Sapporo. While most of Honshu was enveloped in a severe heatwave these days, with temperatures exceeding 40 degrees Celsius alongside high humidity in many places, Sapporo remained pleasantly cool. Walking out of Sapporo Station, the brilliant afternoon sun shone straight down from the cloudless blue sky, accompanied by gusts of cool wind, reminding me of cool summer days in Northern Europe.

Japan never shies away from saying that Sapporo is a colonial city, and there are many memorials to the “pioneering era” throughout Hokkaido. A landmark in the center of Sapporo is the “Former Hokkaido Government Office” (Red Brick Office), a Neo-Baroque building constructed in 1888 that incorporates Japanese decorative elements. I really like such “Japanese-Western Eclectic” (和洋折衷) style architecture from the Meiji and Taisho eras and make it a point to visit them in every city.

Leaving the government office, I walked all the way to Odori Park (大通公園). This is the central axis of Sapporo, built as a belt-shaped park. Escaping the heatwave of Tokyo to avoid the summer heat in a park in Sapporo is exactly the kind of summer I like. Why isn’t Japan’s capital in Hokkaido? If it were, I would be more willing to live there; Sapporo’s climate is much more livable than Tokyo’s. The humid and hot summer in most parts of Japan, including Tokyo, is the season I dread the most.

Before World War II, Japan had multiple ideas about moving the capital, but at that time, the Empire’s ambitions didn’t stop at Hokkaido; Keijo (Seoul) in Korea, Xinjing in Manchukuo, and even Peiping (Beijing) were considered. The Empire’s greed ultimately caused it to lose all colonies except for Hokkaido and Ryukyu. As the most successful Japanese colony, Hokkaido is truly Japan’s “Treasure Island”; without Hokkaido, Japan would be very different.

At the western end of Odori Park is the Sapporo City Archive Museum, a building in the Official Bureau style. The archives are free to visit, containing several exhibition halls that briefly introduce the history of Sapporo. This building used to be the Sapporo Court of Appeals.

Since I had to take a flight to continue to Niigata at 7:00 PM, I returned to New Chitose Airport after a short stay. Compared to when I came in early July, there were now significantly more people in the airport.

Niigata Airport

The flight to Niigata was on a small Bombardier Q400 propeller plane, with only a dozen or so passengers on board, which is the norm for regional flights in Japan. If not bought with airline miles, such flights are usually very expensive, costing at least 30,000 yen. Arriving at Niigata Airport (新潟機場), it was already nearly nine o’clock; this was the last flight. It seemed that everyone else either drove themselves or had someone pick them up, leaving only me preparing to take the bus to the city center. Apart from me, inside the huge airport hall, there was only one staff member sitting lonely inside the information center counter. I went to ask for the bus schedule, and she patiently explained the time, boarding location, fare, and the time required to reach Niigata Station. Throughout Japan, information services for travelers are very professional and polite, a point worth learning by the whole world. After waiting for a few minutes, there was still only me, but the bus departed on time. I was even a bit curious: if there wasn’t a single person, would this bus, which has no other stops in between, still depart?

Uetsu Main Line

After spending a simple night in Niigata, I continued directly north along the Uetsu Main Line (羽越本線), with my destination being Sakata (酒田). There is a limited express train “Inaho” (Ear of Rice) from Niigata to Sakata, and I had purchased a ticket with a 50% discount in advance on the JR East website. Major Japanese railway companies have been suffering comprehensive losses recently, launching significant discount tickets to salvage losses. As the train name suggests, the scenery outside the window on the way from Niigata to Sakata was full of rice paddies, with the sea on the other side, appearing very beautiful. The coastal plains on the Sea of Japan side have been Japan’s rice granary since ancient times because the climate here is very different from the Pacific side, especially with abundant snowfall in winter. However, the summer here is as humid and hot as the Pacific coast, and going out for a stroll in this weather is almost like an ascetic practice.

Sakata

More than an hour later, the train arrived at Sakata. Sakata is located at the mouth of the Mogami River (最上川) and historically was a vital route between the Yamagata interior and the coast, famous for its developed rice trade. Sakata was an important port for the Kitamaebune (北前船 - Northern Bound Ships) during the Edo period, leaving behind many ruins. Although the population is now severely draining away, one can still get a glimpse of the grandeur of that time through these ruins.

Sakata City Museum

I walked from the train station to the Sakata City Museum in the city center to learn about the local history on the spot. The museum has two floors; the lower floor had a special exhibition on the women of Sakata, while the second floor housed the permanent exhibition. The exhibition hall was small, introducing Sakata from ancient times to the present.

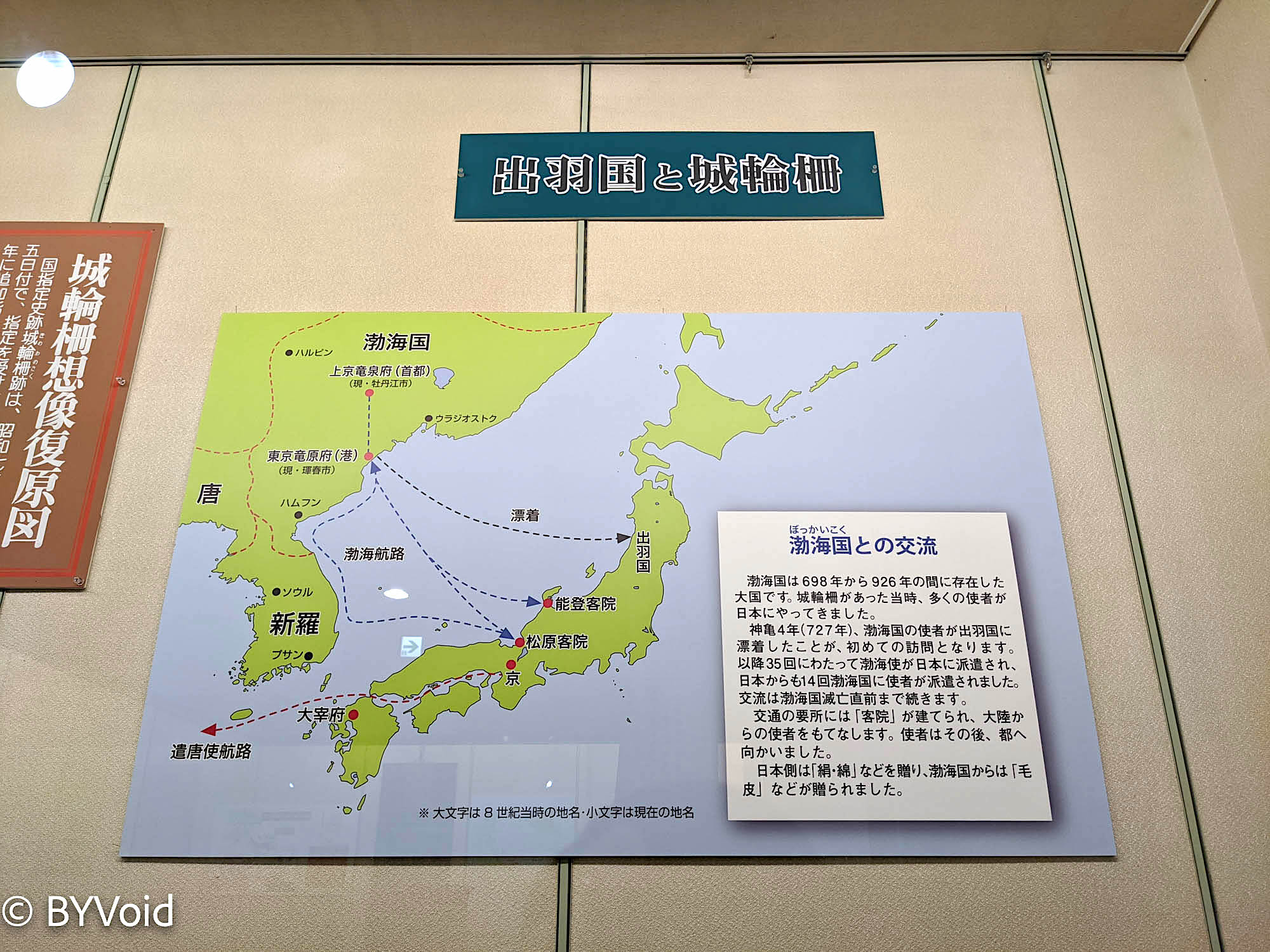

The oldest civilization ruin near Sakata is the Kinowasaku (城輪柵) from the Nara period, discovered archaeologically in 1931. Kinowasaku was a frontline base for the Yamato court’s expedition against the Emishi (蝦夷) and was also the provincial capital of Dewa Province (出羽國) in the late Nara period. The early frontline of Dewa Province was near Akita, its exact location unknown, but later moved south to here due to the Emishi rebellion and the difficulty of radiating control. Japan’s subsequent “Seii Taishogun” (征夷大將軍 - Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians) primarily conquered the Emishi of Dewa Province. The Tohoku region of Japan was the last place on Honshu island to be assimilated, thus retaining some unique culture, which is especially reflected in the Tohoku dialect, considered difficult to understand by other Japanese people. However, historically, the Emishi of Tohoku were different from the Ainu culture of Hokkaido, although the Ainu were also called Emishi in modern times. The Emishi were not entirely equivalent to the Jomon people; like the Yamato people, they also had Yayoi lineage and wet-rice agriculture. The Emishi were eventually assimilated around the 10th century, fully merging into the Yamato people (大和民族).

The museum also mentioned that in 727 AD, the Kingdom of Bohai (渤海國 / Parhae) sent envoys to Japan for the first time. The Shoku Nihongi records that the Bohai ambassador Gao Renyi (高仁義) landed in Dewa Province but was attacked by the Emishi, with only eight people surviving. These eight successfully met the general stationed in Dewa Province and ultimately fulfilled their mission, arriving in Heijo-kyo (Nara) to have an audience with the Emperor. This opened a mutual envoy relationship between Japan and Bohai that lasted for three hundred years. The trade and exchange between the “Flourishing Kingdom of the East” (Bohai) and Japan continued ceaselessly thereafter, with rich historical records. The provincial capital of Dewa visited by this group back then was likely Kinowasaku. Besides this place, I had previously seen the landing site of the 778 AD Bohai envoy Zhang Xianshou at Mikuni Port. Bohai existed from the 8th to the 10th century AD before disappearing into the long river of history. Its mysterious history, unique agricultural culture, and economic structure have always fascinated me. according to historical climatology research, the 7th to 10th centuries were a warm period on the East Asian continent, corresponding to the golden ages of China’s Tang and Northern Song dynasties, which also pushed the frontier of agricultural civilization north to Bohai. The sudden drop in temperature after the 10th century doomed Bohai, and agricultural civilization would not advance here again until the late 19th century. The late development of Northeast China, to the extent that it was expanded upon by Russia, cannot be entirely blamed on the Qing Dynasty’s border ban preventing Han people from flowing into the “Land of the Dragon’s Rise.” The climatic conditions and technological levels before the 19th century destined large-scale agricultural development to be unrealistic.

I didn’t have time to visit Kinowasaku in person this time, leaving it as a reason to visit again in the future. Additionally, the museum narrated later history, including the rule of the Shonai Domain (莊內藩), all the way to the modern era and post-war period. If one wants to understand local history, history museums and archives across Japan are excellent places to go.

Honma Family

Leaving the museum, I continued to wander the streets of Sakata. Perhaps because the weather was too hot, the streets were almost empty, but fortunately, various attractions had begun to open. I walked to the “Honma Family Old Residence” (本間家本邸) to visit the residence of the Honma family, the largest wealthy merchant locally. The Honma clan was a powerful family in Sado Province (佐渡國) since the Kamakura period, and the Honma clan in Sakata was a branch of the Sado Honma clan, owning vast amounts of land in Sakata. Later, the Honma family operated Kitamaebune trade during the Edo period, at one time possessing financial power no less than that of the Mitsui and Sumitomo families. During the Boshin War (to overthrow the Shogunate), the Honma clan supported the Shogunate and faced liquidation after the war, required to pay huge reparations, but they remained the largest zaibatsu in Sakata, contributing significantly to Sakata’s modernization. It wasn’t until after World War II that the land reform led by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers thoroughly hollowed out the Honma family’s assets.

Now, the Honma Family Old Residence is open to the public as a museum, where entering allows a glimpse into the life of the wealthy back then.

The Honma family’s legacy in Sakata also includes the Honma Museum of Art, which opened in Showa 22 (1947) and was later donated to society by the Honma family, becoming a public interest organization.

Sankyo Warehouses

Sakata City’s signature architecture is the Sankyo Warehouses (山居倉庫) built at the confluence of the Mogami River and the Niida River. These are rice granaries built during Japan’s modernization period; nine traditional white-walled earthen storehouses could hold 10,800 tons of rice. In 1893, the Sakai family, daimyos of the Shonai Domain, built this huge warehouse complex to promote trade.

The Sankyo Warehouses are long past being used as rice granaries; they are now a sightseeing spot and a filming location for many movies and TV shows.

Part of the Sankyo Warehouses has been converted into the “Shonai Rice History Museum,” introducing the history, production, storage, and distribution of Shonai rice. Before the Edo period, although Dewa Province was already a rice-producing area, the development of its potential had to wait for the opening of the Kitamaebune Western Sea Route (西迴航路). In 1672 (Kanbun 12), Kawamura Zuiken (河村瑞賢), a merchant for the Edo Shogunate, successfully pioneered a maritime trade route starting from the Mogami River, entering the sea at Sakata, sailing southwest along Japan to Shimonoseki, then along the Seto Inland Sea to Osaka, and finally around the Kii Peninsula to arrive in Edo. Although the distance seemed far, the transport cost was reduced by at least an order of magnitude compared to traversing mountains. Although the Eastern Sea Route, going north up the Tsugaru Strait and then along the Pacific to Edo, had been pioneered by others decades earlier, the Western Sea Route was safer, more reliable, and had more ports along the way.

Sakata has many other places to see, such as the Maiko teahouse “Somaro,” but it was not open due to the COVID pandemic. Additionally, near Sakata, there is the Shonai Domain school Chidokan, as well as the Three Mountains of Dewa. I can visit Sakata again next time to see them.

Rikuu West Line

After leaving Sakata, I headed east along the Rikuu West Line (陸羽西線), following the Mogami River, and arrived in Shinjo (新莊) over an hour later. Shinjo is the junction of the Rikuu Line and the Ou Main Line (奧羽本線). To the east is the Rikuu East Line, ending near Sendai. Interestingly, both names Rikuu and Ou are portmanteaus of Mutsu Province (陸奧國 - Rikuoku) and Dewa Province (出羽國 - Dewa); Rikuu Line runs east-west, while Ou Line runs north-south.

The Rikuu West Line is a non-electrified single track, with river valley scenery all along the way, flanked by typical Japanese countryside.

Approaching Shinjo, the Rikuu West Line merges with the Ou Main Line, and one can see a garage with a century of history.

Shinjo is the starting point of the Yamagata Shinkansen (山形新幹線). This Shinkansen is called a Mini-Shinkansen because its roadbed was not built according to standard Shinkansen specifications; instead, it utilized the existing Ou Main Line (conventional line), simply changing the track gauge to standard gauge (1435 mm). On the platform at Shinjo, one can see the scene of Ou Main Line local trains and the Shinkansen side by side.

Shinjo

Although I had also bought a Yamagata Shinkansen ticket back to Tokyo, the starting station was Yamagata, and I planned to take the Ou Main Line local train for the section from Shinjo to Yamagata. Since the next local train wouldn’t depart for another hour, I decided to visit Shinjo’s city center.

Unsurprisingly, Shinjo is also a small city with massive population outflow. The once most prosperous “Shinjo Ichibangai” (First Street) in the city center was empty, with most shops closed and those persisting having very few customers.

After walking for twenty minutes, I finally reached the ruins of Shinjo Castle (新莊城). The castle is long gone, leaving only the moat, with the Tozawa Shrine (戶澤神社) in the center. Next to the castle ruins is a small history museum containing an introduction to the history of Shinjo Castle and various relics.

After a brief look, I walked back to Shinjo Station and discovered that the building adjacent to Shinjo Station is called the “Mogami River Wide Area Exchange Center.” This exchange center is a civic center, a public facility similar to a library, containing facilities like meeting halls, very different from the dilapidated city center outside. The combination of such decay and newness in Japanese small towns always makes it hard for me to believe it is the same place.

Yamagata

After arriving in Yamagata (山形) by the Ou Main Line train, there was still an hour before the Shinkansen back to Tokyo, so I planned to go out for another stroll. A fifteen-minute walk away is Yamagata Castle (山形城), which is much better preserved than Shinjo Castle. Yamagata Castle was started by the Mogami clan in 1357 and later underwent centuries of maintenance and expansion. Yamagata Castle is a flatland castle (Hirajiro), quite different from most Japanese castles built on mountains with a central tenshu (keep). Since I arrived too late, I couldn’t enter for a visit, so I just walked around the outer moat.

Finally, I took the Yamagata Shinkansen train and returned to Tokyo accompanied by the evening glow. The Yamagata Shinkansen follows the tracks of the Ou Main Line until Fukushima, then merges onto the Tohoku Shinkansen to begin traveling at full speed.

Last modified on 2021-10-15