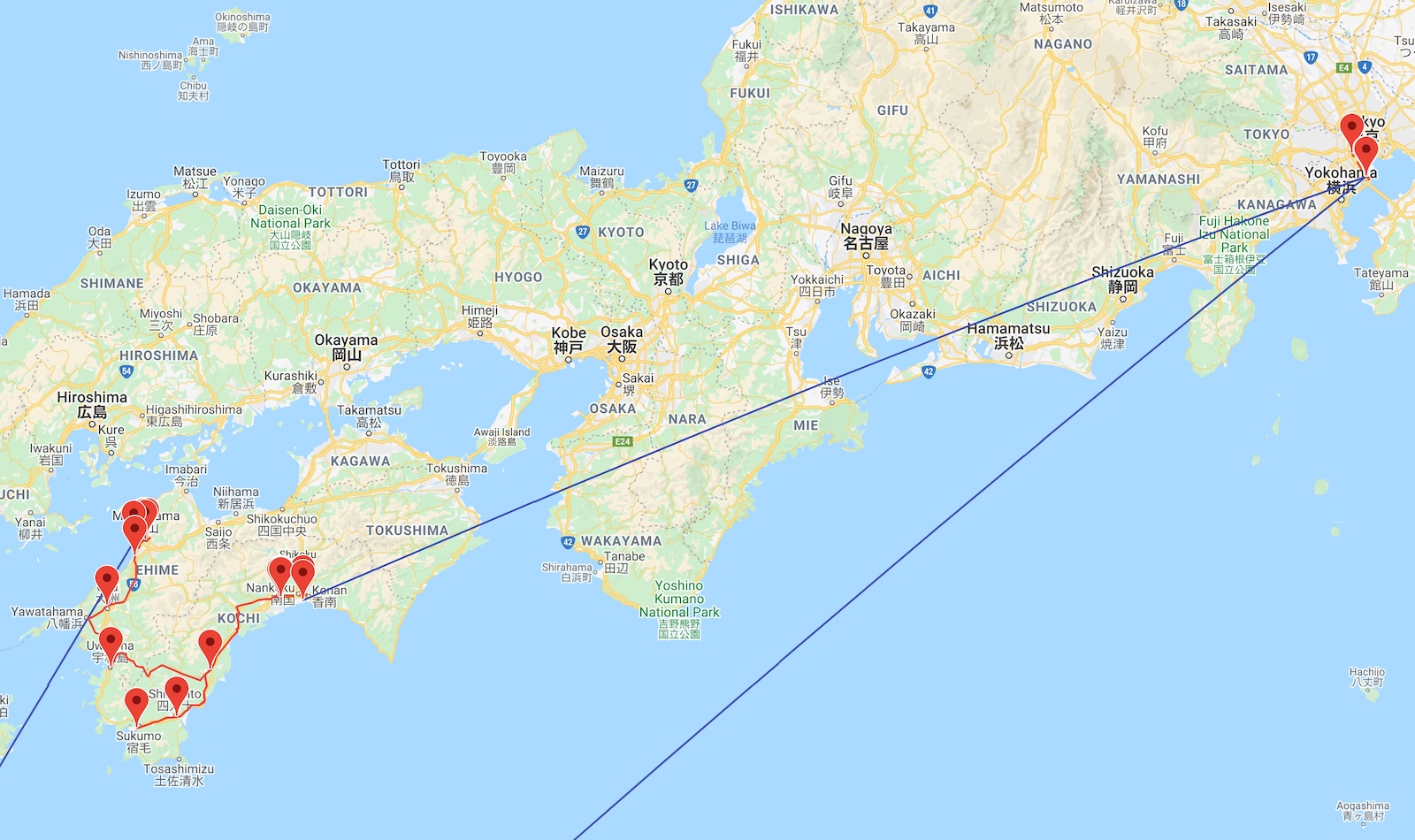

At the end of July 2020, taking advantage of the consecutive holidays originally intended for the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympics, I decided to visit Shikoku and Okinawa again (Itinerary Map).

Kochi (高知)

The rainy season was finally coming to an end, followed by Japan’s most sweltering and humid midsummer. Domestic flights at Haneda Airport had recovered to nearly half their usual volume, and the terminal was returning to its former hustle and bustle. The plane I took was parked at a remote stand, requiring a bus ride from the boarding gate. After a flight of over an hour, the plane landed at Kochi Airport. Stepping off the plane, a wave of heat hit me. It was already 32 degrees Celsius in the early morning, which, combined with a relative humidity of over 90%, was unbearable.

This was not my first time in Kochi; I had visited in April 2019, but it rained the entire time. Although April is not the rainy season, the side of Shikoku facing the Pacific Ocean receives extremely abundant rainfall, making it the “rain pole” of Japan. Conversely, the Seto Inland Sea coast on the other side of the Shikoku Mountains is the place with the least rainfall in Japan. This time Kochi was sunny, but simply too hot. I took a bus to the city center and got off at Harimayabashi (播磨屋橋). The temperature continued to rise above 35 degrees, and the moment I got off the car, I lost the motivation to walk around the streets. Nevertheless, I braved the scorching sun to walk over and see the famous Harimayabashi. Harimayabashi was once a small private bridge in the Edo period, built by the local merchant Harimaya, hence the name. Later, this area became the core of the Kochi castle town (Jōkamachi), and even now, it remains the intersection of two Tosaden Kōtsū streetcar lines.

Continuing west from Harimayabashi, I walked all the way to the vicinity of Kochi Castle Park, passing several empty shopping streets. Perhaps it was because it was too early in the morning, so they hadn’t opened yet. There is a history museum at the entrance of Kochi Castle Park. The building looks beautiful from the outside, and the interior decoration is a modern Japanese design. I had already seen it when I came last year, so I just enjoyed the air conditioning inside for a few minutes before leaving. This time inside the museum, I noticed that Kochi Castle lies between two rivers and was originally called “Kauchiyamajō (河內山城)”. Later, due to phonetic shifts, “River” changed from “kahakapa” to “kawakawa” (Ha-row shifting), where “wawa” merged with “uu” to become “kautikauti”, taking the kanji “Kautiyamajō (高智山城)”. Later still, “Ti (智)” merged into “Chi (知)”, becoming today’s “Kochi Castle (高知城)”. After the implementation of Modern Kana Usage, the kana became “kōchikōchi”.

I had intended to climb Kochi Castle again, but the weather left me with absolutely no energy. I took the streetcar back to Kochi Station and bought a limited express ticket to Sukumo.

Sukumo (宿毛)

The train from Kochi to Sukumo travels via the Dosan Line, the Nakamura Line, and the Sukumo Line. The limited express train I took only went from Kochi to Nakamura, where I had to transfer to another train for Sukumo. Upon entering the station, I saw a train with only two cars parked at the platform. Its exterior was worn, and I initially thought it was a local train. However, since I didn’t see any other trains, I double-checked and realized this was indeed the limited express I was to take. It was my first time seeing such a dilapidated limited express train in Japan; Shikoku Railway Company (JR Shikoku) is indeed in financial difficulty. In these two cars, the front half of Car 1 was reserved seating, and the rear half was non-reserved. The train was diesel-powered, the tracks were not electrified, and the ride was very bumpy due to limited maintenance. Although called a “Limited Express,” its operating speed was not fast, and it made many stops along the way, averaging less than 100 kilometers per hour. Yet, the ticket was not any cheaper than elsewhere. However, thinking that JR Shikoku is still struggling to operate, I considered the extra cost a donation to protect historical heritage.

Although the train goes directly to Nakamura, the section from Kubokawa to Nakamura is actually owned by another company, the Tosa Kuroshio Railway. The line from Kubokawa to Nakamura was the Nakamura Line of the Japanese National Railways (JNR) era. Later, when JNR was broken up, this railway was taken over by a “Third Sector Railway” formed by the local government, which is the current Tosa Kuroshio Railway. Upon arriving at Nakamura, I switched to a local train to continue to Sukumo. The section from Nakamura to Sukumo is the Sukumo Line operated by the Tosa Kuroshio Railway. The Sukumo Line is a branch line built after the breakup of JNR, which is rare outside of Japan’s major metropolitan areas. JNR’s original plan was to extend the Nakamura Line all the way to Uwajima, but this plan was cancelled after finances deteriorated in 1980. Surprisingly, the Tosa Kuroshio Railway continued construction in 1987, and it was finally completed in 1997. As for the section from Sukumo to Uwajima, it is likely impossible to realize in the future; just keeping the current section from being abolished is difficult enough.

After arriving in Sukumo, I wandered around the station area before starting my return journey. The area surrounding Sukumo Station is farmland, along with several cheap large shopping malls with huge parking lots in front, somewhat resembling the American countryside. The Japanese countryside actually relies heavily on private cars, and public transportation is very inconvenient. I wonder if it was influenced by American urban planning after the war; aside from big city centers, American-style shopping plazas are numerous and distributed along major traffic routes. Main streets in small towns are conversely quite desolate, bearing similarities to the decay of American city centers.

Kubokawa (窪川)

After thirty minutes on the train, I returned to Nakamura Station. Considering the next train was in half an hour, I wandered around the station again. Regrettably, apart from a small town on the decline, there was nothing nearby.

Another hour after boarding, I returned to Kubokawa, which is the junction of the Yodo Line, Dosan Line, and Nakamura Line. My next destination was Uwajima at the other end of the Yodo Line, so I walked around the vicinity while waiting for the train. Not far from Kubokawa Station is Iwamotoji (巖本寺), the 37th temple of the Shikoku Pilgrimage (Shikoku 88 Temples). Iwamotoji belongs to the Shingon sect, and its most distinctive feature is the painted coffered ceiling in the main hall, featuring 575 exquisite paintings.

Returning to Kubokawa Station, I boarded a train originating from this station on the Yodo Line heading to Uwajima. The name Yodo Line (豫土線) is taken from Iyo Province (伊豫國) and Tosa Province (土佐國), which are present-day Ehime and Kochi prefectures respectively. There are very few trains on the Yodo Line each day, and there are no limited express trains, but I happened to get on a sightseeing train called the “Kaiyodo Hobby Train”.

This train weaved through deep mountains and gorges the entire way. The route was sparsely populated, and my phone often had no signal. As the sky gradually grew dark, the train drove out of the mountainous area. After a total of over an hour, we finally reached the terminus, Uwajima.

Uwajima (宇和島)

The scenery outside Uwajima Station is quite unique, with many palm trees. This is because Uwajima promotes a “Southern Country” characteristic, so this batch was planted artificially.

Since I was in Uwajima, I couldn’t miss tasting the local specialty, Tai-meshi (Sea Bream Rice). I went to a restaurant called “Kadoya” near the station and ordered the Date Gozen. Uwajima is located in the southern part of Iyo Province, also known as the Nanyo region, and Nanyo Tai-meshi is a local specialty. The way to eat Tai-meshi is to first dip sea bream sashimi in a sauce made of dashi, soy sauce, and raw egg, and then pour the sauce over rice.

Early the next morning, the weather was still sunny, and it was still as unbearably hot and humid as the day before. I arrived at Tenshaen (天赦園) at 8:30. Tenshaen is a famous circuit-style garden in Uwajima. Although it was a holiday, I was the only visitor in the garden in the morning. Actually, visiting Japanese gardens in midsummer is not a very good experience because there are too many insects, especially spider webs everywhere; if you’re not careful, they stick to you.

After touring Tenshaen, I went to the nearby Date Museum, which exhibits historical artifacts of the Date family. The Date family were the daimyo (feudal lords) who ruled the Uwajima Domain for 400 years, with Date Hidemune as the ancestor. Date Hidemune was the eldest illegitimate son of Date Masamune of the Sendai Domain and was enfeoffed in Uwajima. However, the Uwajima Domain did not have a subordinate relationship with the Sendai Domain. There aren’t many exhibits in the museum, but it reflects that various places in Japan still commemorate the daimyo families that once ruled them.

Next, I started climbing the mountain to see Uwajima Castle. The castle keep (Tenshu) of Uwajima Castle is one of the twelve existing original keeps in Japan, not a modern reconstruction. The climb was very arduous, not because the mountain was high, but because the weather was too hot, and wearing a mask made breathing particularly difficult. The interior of the Uwajima Castle keep is open to visitors, but photography is prohibited. The keep is small in scale, with only three stories. There is also a Castle Mountain Folk Museum on the mountain, which exhibits the deeds of many local celebrities.

After descending from the north side, I walked north for another twenty minutes to visit Taga Shrine. Although I only walked for twenty minutes, the blazing sun and humidity made me feel like I was going to suffocate. The reason for visiting Taga Shrine is that this shrine has Japan’s largest collection of sex worship items. Taga Shrine is also known as Dekoboko Shindō (凸凹神堂), and the shrine has a three-story museum that collects items related to sex culture from Japan and all over the world; its breadth is breathtaking. Photography is generally prohibited; if you need to take photos, you need to pay a fee of 20,000 yen.

After seeing Dekoboko Shindō, I walked along the river to Warei Shrine. Upon returning to Uwajima Train Station, I was soaked through with sweat; Japan’s midsummer is truly grueling. My next destination was Ozu (大洲), which takes about 50 minutes from Uwajima via the Yosan Line.

Ozu (大洲)

Similar to Uwajima, Ozu was also once the stronghold of a domain. The Ozu Domain was slightly smaller than the Uwajima Domain, but its castle town (Jōkamachi) has been preserved with more of its original flavor. It takes more than twenty minutes to walk from Iyo-Ozu Train Station to the castle town, but there is a bus connection. The center of Ozu is called Honmachi, and the streets still have a Meiji-era feel.

The first thing that attracted me was the Ozu Red Brick Hall, a 1901 eclectic Japanese-Western style building that was originally the Ozu Commercial Bank. Many small towns in Japan have similar bank buildings from that era, which were symbols of civilization and enlightenment at the time.

Next to the Red Brick Hall is a restaurant called Aburaya. Although it was already past 1 PM, there was still a line for dining. This restaurant has a long history; the building is an old folk house (Kominka), and the interior decoration is bright and elegant. I enjoyed the shop’s specialty: pork and chestnut rice.

After lunch, I continued sightseeing around Honmachi. Right next to the Red Brick Hall is a tall river embankment. The embankment protects the small town like a city wall and has gates to facilitate entry and exit.

Walking a little to the east is a famous sightseeing spot in Ozu called “Pokopen Yokocho” (不彀本Pokopen Alley). This is a retro market that is only open on Sundays. Although it was empty, I went in to take a look. The most interesting thing is actually its name. The word “Pokopen” comes from “Soldier Chinese” (Heitai Shinago)—simplified Chinese spoken by the Japanese military. The so-called “Pokopen” derives from the phrase Chinese peddlers used when bargaining: “Bù gòu běn” (不夠本 - not enough capital/at a loss), which was understood as a refusal, equivalent to the Japanese “Dame” (No good). This word was later brought back to Japan by the army following Japan’s defeat and turned into the name of a game played by children. The “Pokopen” here likely takes its name from this game, representing a nostalgia for the Showa era.

Continuing east along the river embankment, I arrived at Ozu’s most famous garden, Garyu Sanso (Wandering Dragon Villa). Garyu Sanso is built on a cliff by the river and features several buildings in the style of Japanese tea houses, with elegant interior decorations. At the end of the garden is a square pavilion called Furo-an; half of the pavilion is built out over the cliff, supported by wooden pillars from below. The pavilion offers a panoramic view of the river scenery.

After viewing Garyu Sanso, I walked through the castle town all the way to Ozu Castle in the west. Ozu’s castle town is well preserved; a large number of wooden old houses and white walls recreate the characteristics of the Edo period. Ozu Castle is built on a hill by the river and features a reconstructed castle keep. This reconstructed keep employed traditional construction methods as much as possible and is a purely wooden structure, distinctly different from concrete buildings like Osaka Castle.

After spending a pleasant afternoon in Ozu, I slowly walked back to Iyo-Ozu Station to continue to Matsuyama. I got off early at Iyo City (Iyoshi) and switched to the Iyotetsu local train, which goes directly to the center of Matsuyama; this line is used by many commuters.

Matsuyama (松山)

This was my second time in Matsuyama. Matsuyama’s most famous sightseeing spot is Dogo Onsen, but I didn’t go there again this time; instead, I went to sleep early at a hotel in the city center. The next morning, it started to rain, and it finally cooled down a bit. In the early morning, I climbed to Shinonome Shrine halfway up the mountain. The mountain was devoid of people, and the scenery was refreshing and quiet.

Having finally cooled down a bit, I was, however, about to continue to Okinawa, where the heatwave was waiting for me ahead.

Last modified on 2021-03-14