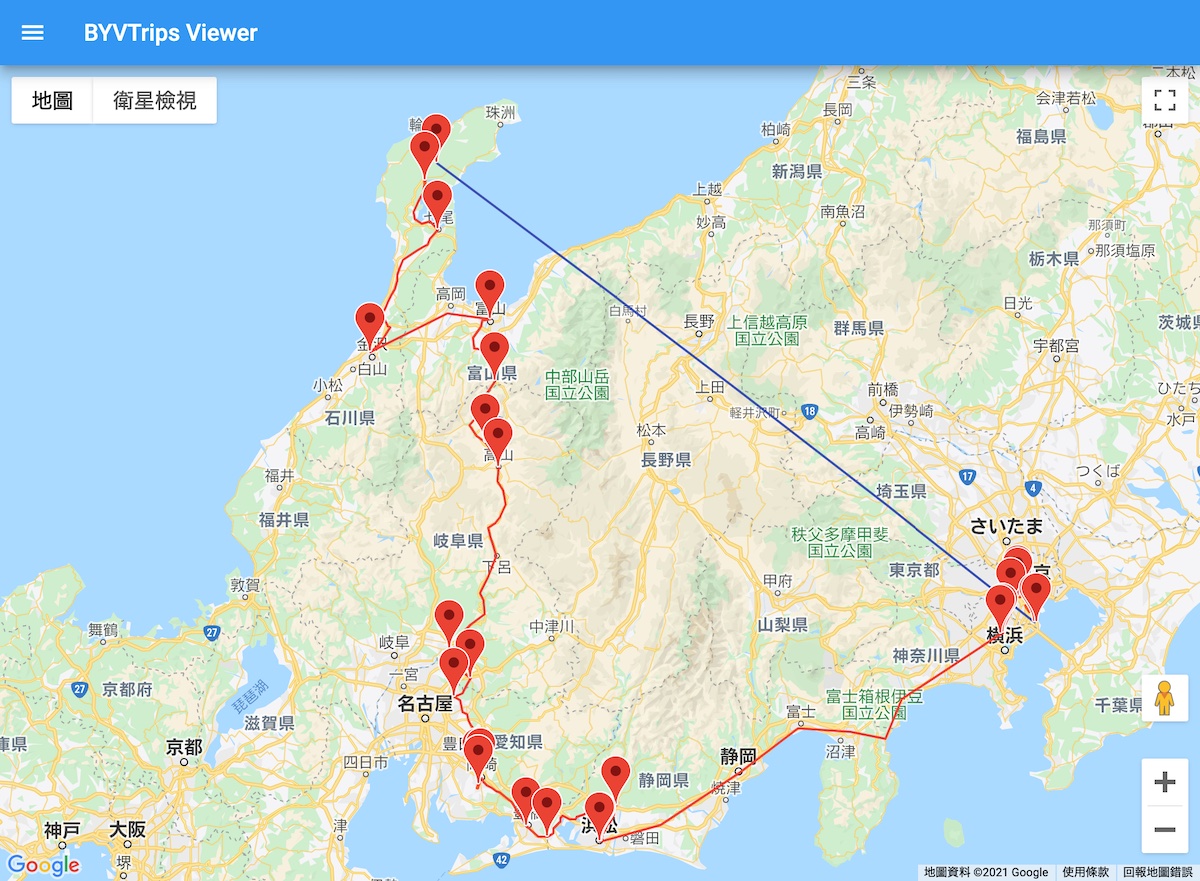

After hibernating at home for three months, a glimmer of hope finally appeared. Given that the pandemic situation in various regions was flattening out, I embarked on my “Wandering in Japan” journey again in late June 2020. For this trip, I chose to fly first to Wajima in the Hokuriku region, then take trains to traverse Central Japan from north to south, reaching the Nagoya area, and finally returning via the Tokaido.

Wajima to Toyama

I got up early in the morning and rushed to the fifth floor of Shibuya Mark City to take the airport bus. I was the only person on the bus, yet it departed and operated on schedule. Since there were almost no cars on the road, traffic was smooth, and it took only twenty-some minutes to reach Haneda Airport. This was significantly faster than the train, but the price was correspondingly more expensive at 1,050 yen.

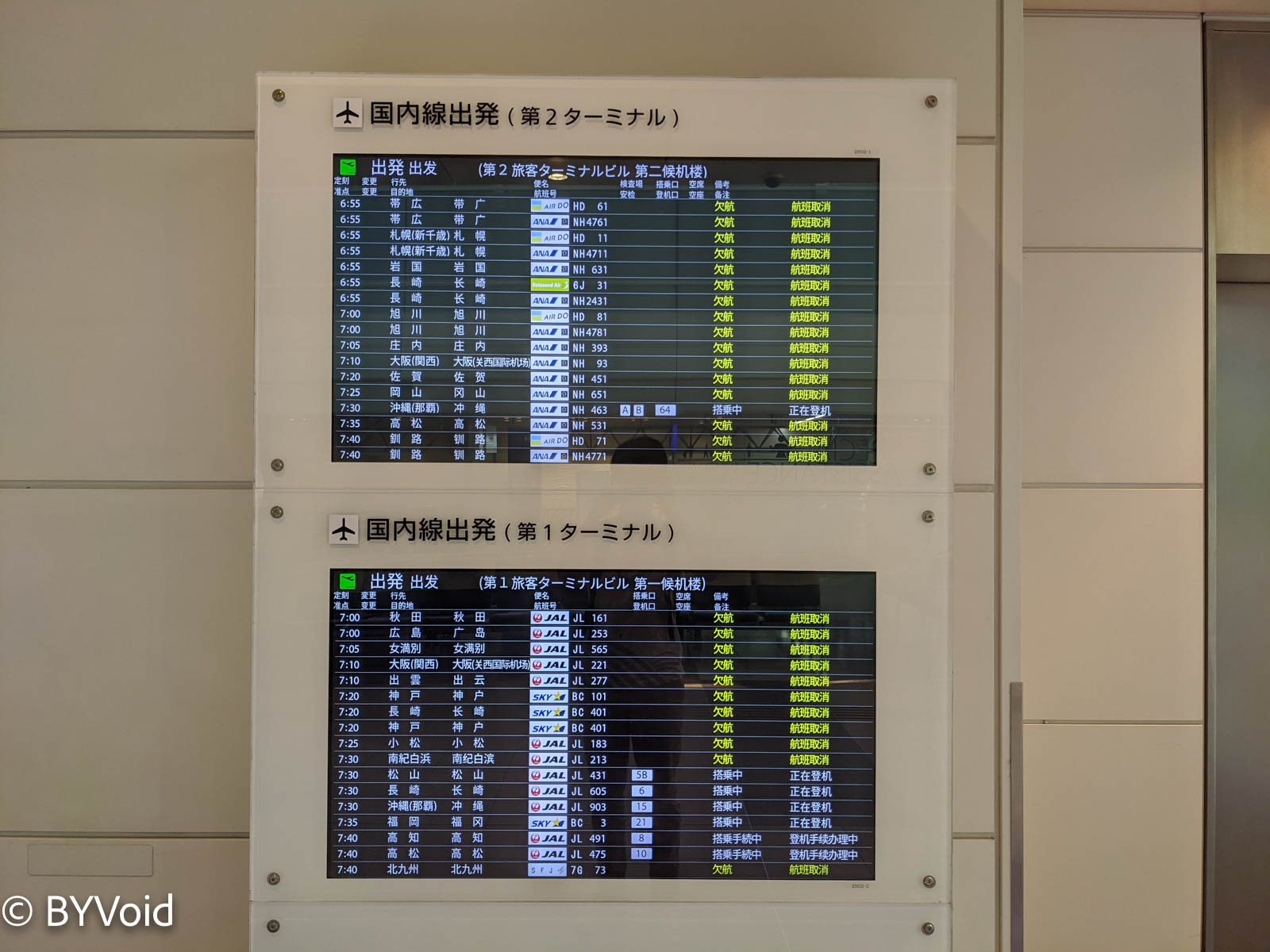

Arriving at Haneda Airport again after several months, I had a strong sense that things had changed. Although the State of Emergency had been lifted, the foot traffic at the airport was clearly far below what it used to be, and one could see that most flights were still “cancelled” (缺航). The ANA terminal was even half-closed, with all aircraft concentrated at the North Wing. I wonder how long it will take for Haneda Airport to return to its former hustle and bustle.

After a flight of less than an hour, the plane arrived at Noto Satoyama Airport, located on the Noto Peninsula. As the plane descended, it entered from the bay on the east side, offering beautiful scenery. Currently, Noto Satoyama Airport has a mere one flight per day, but even so, the airport’s tourist information center was open as usual, and there were even staff members who spoke English. Once the passengers from this flight had left one by one, the shops packed up. It is evident how much Japan’s regional areas hope for the tourism industry to recover as soon as possible; after all, for many places, tourism is the economic lifeline.

I purchased an airport connection ticket at the airport, which included the bus from the airport to Anamizu Station and the train fare from Anamizu to Nanao. Experiencing the Noto Railway was one of the reasons I flew to Noto Satoyama Airport. Local railway companies in Japan are gradually dying out; in the future, they might cease to exist after a single natural disaster. The journey from Anamizu Station to Nanao Station takes forty minutes, with beautiful scenery of rice paddies and bays along the way. After a short stop in Nanao, I transferred to the JR West Nanao Line bound for Kanazawa. Actually, the Nanao Line only runs from Nanao to Tsubata; from there, the train continues onto the IR Ishikawa Railway tracks. This kind of through-service operation between different companies is very common in Japan, especially with the Tokyo Metro, where almost every line connects with other companies.

After arriving in Kanazawa, I didn’t stay but immediately headed for Toyama. From Kanazawa to Toyama, I took the Hokuriku Shinkansen Tsurugi (劍) train, which takes only 22 minutes. The Hokuriku Shinkansen is still under construction; currently, the section from Tokyo to Kanazawa is open, with operations split between JR East and JR West at Joetsumyoko. The Tsurugi train only operates on the section between Kanazawa and Toyama. Including Shin-Takaoka in the middle, there are only three stations, yet there are 18 round trips per day. The train has 12 cars; after boarding, I found that all cars were empty, and I was the sole passenger. Even without the virus’s blow to the tourism industry, it would be difficult to have many people on such a short-distance, high-frequency Shinkansen, especially since neither Kanazawa nor Toyama can be considered large metropolises. JR West’s reason for operating the Tsurugi is truly baffling. If it doesn’t make sense economically, then it is likely a political compromise, given that the Hokuriku Shinkansen is a government-funded “Seibi Shinkansen” (planned Shinkansen). I suspect that perhaps the Shinkansen is intended to replace the previous Limited Express trains with the same frequency, because once the Shinkansen opens, the regular trains often cease operation. In the past, the Limited Express train from Osaka to Niigata was also called Tsurugi.

Hida

After arriving at Toyama Station, I transferred to a local train on the Takayama Main Line and arrived at Inotani after an hour of slow travel. This is the boundary point for the Takayama Main Line operated by JR West and JR Central. Looking at the topographic map, one can see that this is where two valleys meet; controlling Inotani means controlling the vital route for entering and exiting Etchu Province (Toyama) from Hida Province.

After transferring to a JR Central local train, another hour passed before I finally arrived at my destination, Hida Furukawa. Hida Furukawa is a small town nestled in the middle of a valley. Its most famous attraction is the Setogawa Canal and White-walled Storehouse Street. In this modest town, there are three large temples and several Japanese sake breweries, along with a canal running through the town. The water in the canal is crystal clear, and hundreds of koi carp swim within it.

On the way, I saw a beauty salon named “Corona” (コロナ) that had closed down.

After spending a peaceful afternoon in Hida Furukawa, I returned to the train station to continue to Takayama, the final destination of the day. Takayama is a renowned sightseeing town that attracted a large number of foreign tourists in the past. I had been here once before and remembered the small streets were woven with tourists; combined with the quaint wooden houses and stone-paved roads, the atmosphere was very much like Kyoto. Coming here again this time, the streets and alleys were almost empty. I walked through the streets of Takayama and arrived again at the entrance of the Takayama Jinya, only to find the gates locked tight. Crossing the small bridge to the most famous Sanmachi Historic District, there were merely a handful of people. I followed the path up the mountain to see the ruins of Takayama Castle, but when I reached the Ninomaru (second bailey), I saw a warning about bears in the area and decided to head back down. Being near the summer solstice, the sun had not yet set at 6 PM; the light was soft, making the woods appear exceptionally bright.

Walking slowly down the mountain, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the Hida Takayama Museum of History and Art was not yet closed. It is extremely rare for museums in Japan to operate past 5:30 PM. The museum is not small, with over a dozen exhibition rooms across two floors to visit. Each hall has a theme covering many aspects of Takayama’s history and culture, among which the restoration model of Takayama Castle is quite exquisite.

It was almost 7 PM when I finished the museum, so I walked to Hida Kokubun-ji Temple before sunset. Kokubun-ji (provincial temples) were all built during the Nara period, and few remain intact today; Hida Kokubun-ji is no exception. The current three-story pagoda in the temple was rebuilt in the late Edo period. However, this is the only pagoda in Hida Province. Since the Heian period, Japan almost stopped building new pagodas, focusing instead on the construction of Buddha halls and statues. This reflects the shift in the object of worship in Han Buddhism from the Dharma to the pagoda (stupa), and then to the Buddha image.

Under the afterglow of the setting sun, I returned to Takayama Station. The pool and lighting in front of the entrance made this modern-style building appear dreamy and charming.

Okazaki

At seven o’clock in the morning, the sunlight was already dazzling. In Japan’s gloomy rainy season, such weather is rare. I immediately hurried to the train station and took the Takayama Line Limited Express Hida to continue south. I bought a non-reserved seat ticket and, after boarding, found that I was the only passenger on the train starting from Takayama. The train headed south, weaving through the river valley, with constantly changing streams and lakes outside the window. After an hour and a half, the train drove out of the valley and entered the flat Nobi Plain, where I got off at Mino-Ota. The Nobi Plain is Japan’s third-largest plain and the location of Greater Nagoya; its name is derived from Mino Province and Owari Province. From Mino-Ota, I continued on the Taita Line via Tajimi, transferred to the Chuo West Line to Kozoji, and then transferred again to the Aichi Loop Railway to reach Okazaki.

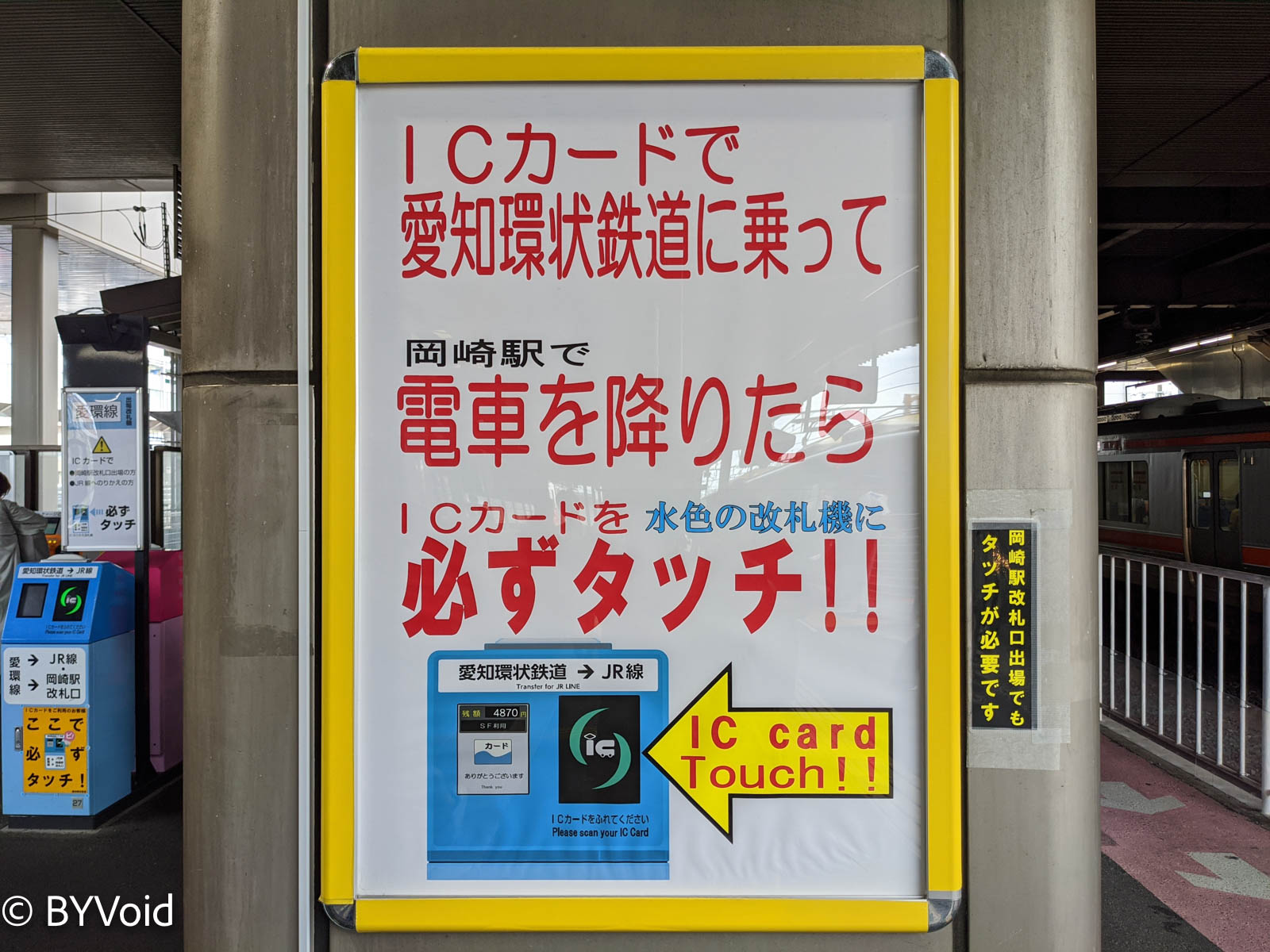

The Aichi Loop Railway does not belong to JR Central, yet it offers cross-platform transfers with JR Central trains. Generally speaking, Japanese railway fares are calculated by route, but if you use a transportation IC card, it calculates the fare based on the shortest path between the entry and exit stations according to the lines traversed. This is not a problem within the same company’s railway network, but issues can arise involving cross-platform transfers or through-services with other companies, because the shortest path between two points is not necessarily the cheapest, and considering the issue of revenue sharing between different companies, knowing the exact route is necessary. The journey from Kozoji to Okazaki is one such example, as one can travel between these two stations either by transferring via JR Central or directly via the Aichi Loop Railway. The solution at Okazaki Station is to set up additional card readers on the platform; as long as you tap once on these machines and tap again when exiting, the fare can be calculated correctly. Even so, many people still get it wrong, which can only be resolved manually. Japan’s automatic fare collection system has developed slowly since the 1970s and could be said to have been world-leading both then and in recent years. However, with the rise of electronic means, Japan has started to slowly fall behind the times. One example is that almost none of the Japanese railways support electronic tickets very well; in particular, online ticket reservation is extremely difficult for foreign tourists.

Although Okazaki is not far from Nagoya and is considered a satellite city, the entire city is very dispersed and public transportation is poor. Among Japan’s major metropolitan areas, Nagoya has the worst public transportation, the highest rate of private car ownership, and the most scattered facilities; it could be called the Los Angeles of Japan. Speaking of Los Angeles, one cannot help but be reminded of that conspiracy theory; I wonder if Nagoya’s situation is related to being the location of Toyota’s headquarters. Of course, even if public transportation is poor here, that is in comparison to the Japanese average; it is still far better than in the United States.

I got off at Okazaki Station, took a bus to Higashi Okazaki Station, found a very Showa-style shopping center basement nearby to have lunch, and then walked to Okazaki Park. Okazaki Park was once the site of Okazaki Castle; stone walls still remain, atop which sits a reconstructed castle keep (Tenshu). The keep is a reinforced concrete restoration with an observation deck on the top floor. There is also a museum in the park introducing the life of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Edo Shogunate. Tokugawa Ieyasu was born in Okazaki Castle; his original name was Matsudaira Takechiyo, and his father was a local daimyo. Later, as Ieyasu rose to power, the Emperor bestowed the surname Tokugawa upon him.

If we don’t count the anti-shogunate war during the Meiji Restoration, the Sengoku period (Warring States period) was the most recent time of “great chaos under heaven”; therefore, historical records are detailed and vivid, making it the history Japanese people delight in discussing the most. Most of the historical ruins like city walls seen in Japan today date from the Sengoku period onwards, and even many thousand-year-old temples underwent major repairs during the Edo period, so the Japan of today was essentially established around that time. Similar to the Japanese Sengoku period is the Three Kingdoms period in China; because of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and subsequent Japanese manga adaptations, the Three Kingdoms is the period of Chinese history most familiar to Japanese people. The Japanese game company Koei released two games, Nobunaga’s Ambition and Romance of the Three Kingdoms; the gameplay is very similar, and both are masterpieces.

After visiting Okazaki Castle, I continued my journey eastward. First, I took the Meitetsu (Nagoya Railroad) from Higashi Okazaki to Toyohashi, then took the Tokaido Line to the unassuming station of Shinjohara, where I boarded the Tenryu Hamanako Railroad. This railway connects Toyohashi and Kakegawa, bypassing Lake Hamana to the north. It used to be the Japanese National Railways (JNR) Futamata Line, but was later abandoned during the JNR privatization and established as a third-sector railway funded by local governments. There are quite a few of these third-sector railway companies, all born as successor operators because political resistance prevented the removal of unprofitable lines. Strictly speaking, these third-sector railways are private railways aiming for profit, but in reality, the assets they inherited are incapable of profitability, so they rely mainly on subsidies. Amtrak in the United States is essentially this type of company, just on a larger scale and with even more entrenched problems.

The tracks and carriages of the Tenryu Hamanako Railroad were truly in a state of disrepair, and even the interior cleaning was lacking. The scenery along the line was also just average.

At Nishi-Kajima Station, I got off the Hamanako Railroad and transferred to the Enshu Railway. The Enshu Railway is a genuine private railway; besides operating trains, it also has various real estate holdings centered in Hamamatsu. In fact, most private railways in Japan make money from real estate; the railway business often serves merely to raise property values, operating through cross-subsidization. I saw Enshu Railway’s real estate advertisements both on the train and inside the stations. The name “Enshu Railway” (遠州鐵道) comes from “Totomi Province” (遠江國 Totomi-no-kuni); “Totomi” was originally written as “Distant Freshwater Sea” (遠淡海 To-ho-tsu-awa-umi), referring to Lake Hamana. Among Japan’s provinces under the Ritsuryo system, there was also “Omi Province” (近江國), where “Omi” (Near Freshwater Sea) referred to Lake Biwa. The “distant” and “near” here are relative to the Kinai region, which is the area around Nara and Kyoto.

By the time I arrived in Hamamatsu, it was already evening. The Hamamatsu train station building is massive, and the plaza outside the station is quite stylish. Connected to the train station via an underground passage is the bus terminal; the lower level of the bus terminal is a sunken plaza with a unique structure. Surprisingly, I saw quite a few Indonesians there setting up stalls selling Mie Goreng (Indonesian fried noodles); I didn’t expect Hamamatsu to be somewhat international. In fact, Hamamatsu is a city with a high proportion of foreigners, mainly because there are many factories in the surrounding area. Since the 1990s, it has attracted many Japanese-Brazilian and Japanese-Peruvian immigrants, and in recent years, it has attracted many Southeast Asians.

After a simple dinner in Hamamatsu, I took the Shinkansen back to Tokyo.

Last modified on 2021-02-23