Ever since my last failed attempt to enter Kosovo from Macedonia resulting in repatriation, Kosovo has always been on my mind. A few days ago, I traveled to southern Serbia, and took the opportunity to make a trip to Kosovo. When Kosovo is mentioned, many people ask, “Is it safe there?” or “Is there still a war?”. In fact, 16 years have passed since the Kosovo War, and in the vast majority of places, the traces of war are no longer visible; the scars of war can only be seen in the hearts of the local people.

The “Quasi-State” of Kosovo

However, Kosovo is not yet a widely recognized independent country, as it only declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Since it was a unilateral declaration of independence, Serbia still considers Kosovo an “inseparable part” of Serbia. Furthermore, countries led by Russia and China do not recognize Kosovo’s independence, whereas the United States and most Western European countries recognize Kosovo as an independent sovereign state.

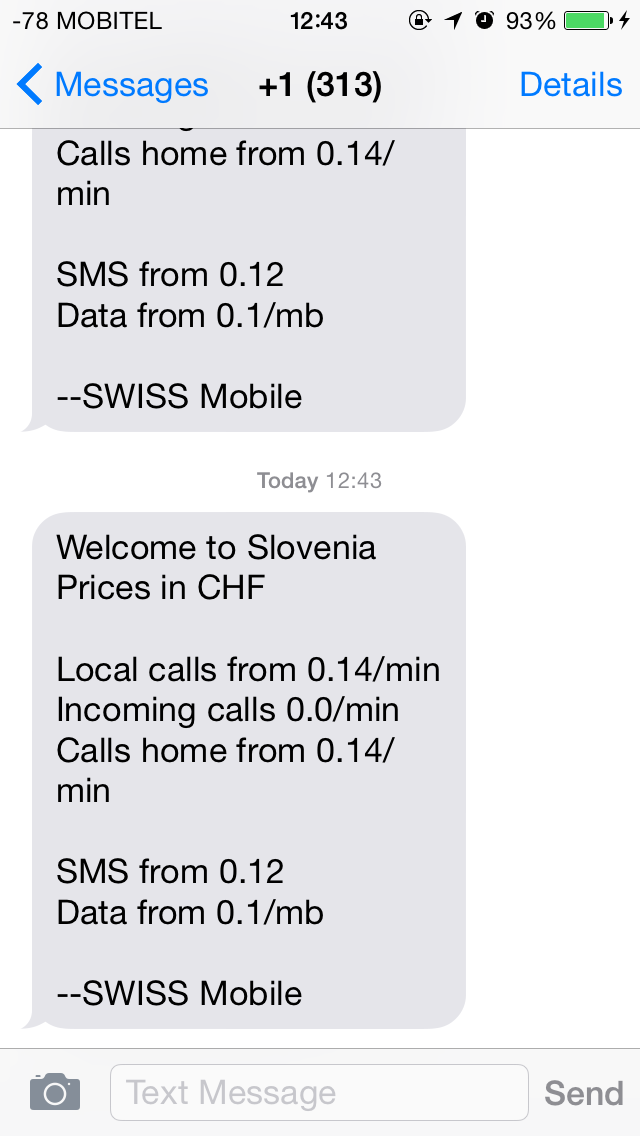

Telecommunications

Due to this situation, Kosovo can only be considered a “quasi-state,” leading to many unique situations, such as Kosovo’s telecommunications industry. Kosovo has two major telecom operators: IPKO and Vala. IPKO is an operator owned by Telekom Slovenije, and its mobile numbers start with +386, just like in Slovenia. Vala is managed by Monaco Telecom, so its mobile numbers start with Monaco’s country code +377. As for Serbian telecom operators, there is signal in some areas of Kosovo, especially in the Serb-controlled areas of northern Kosovo, where only Telecom Serbia has coverage. Actually, Kosovo has its own international calling code, +383, but for some reason, it has not yet been activated. When I was traveling, my phone roamed onto the IPKO network, and I received a text message saying “Welcome to Slovenia,” and the roaming charges were the same as in Slovenia.

Map Names

When using Google Maps on my phone, I noticed that addresses only pinpointed the city name, not Kosovo or Serbia. iPhone Photos and Weather didn’t even display the location name. Not long ago, to avoid protests from the Philippines, Google removed the Chinese name for “Scarborough Shoal” (Huangyan Island), but then faced dissatisfaction from China. Thinking about it, these companies really walk on thin ice; geographic names can easily trigger political controversy, and ultimately, it is the shareholders’ interests that suffer. Speaking of place names, they can differ significantly across languages, often mixed with national sentiment; a slight slip can hurt the feelings of a particular ethnic group. In Central Europe, a region rife with ethnic strife, every city has names in several languages. For example, “Geneva” (Latin Geneva) is Genève in French, Ginevra in Italian, and Genf in German. And “Milan” (Milano in Italian) is called Mailand in German, which sounds as if it were Germanic territory (Germanic -land).

Deutsche Mark and Euro

The legal currencies of Kosovo are the Euro and the Serbian Dinar, but the Dinar circulates only in Serb-populated areas, while the Euro circulates elsewhere. It is worth mentioning that Kosovo is not a Eurozone country but unilaterally chose to use the Euro as its currency. A country similar to Kosovo is Montenegro, which is also a non-EU country that uses the Euro. This situation has historical roots: in the 1990s, before the birth of the Eurozone, the Balkan Peninsula was plagued by war, and many regional economies collapsed. Consequently, under UN intervention, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Kosovo began using the Deutsche Mark directly as currency or issued currencies convertible one-to-one with the Deutsche Mark. After the birth of the Eurozone, Kosovo and Montenegro immediately switched to the Euro, while Bosnia continued to issue the “Convertible Mark,” pegged to the Euro.

In my opinion, as a small developing country, voluntarily giving up the right to issue currency is a good thing. Monetary policy is a dangerous tool and a gateway to a planned economy and servitude; without strong constraints, it is easily abused, causing national economic collapse. Under the premise of using the Euro, the moral hazard of the government over-issuing currency and national debt is constrained, and citizens’ private wealth is protected. If a country has the ability to issue currency, politicians can easily squander wealth by issuing national debt, spending beyond their means, and finally having to “monetize” the debt, damaging the personal wealth of all citizens. Without the right to issue currency, government debt must be repaid, otherwise, it can only default and go bankrupt, just like Greece today. Seeing the tragic fate of Greece today, other European countries will be wary of recklessly issuing national debt.

Pristina

Kosovo is a young country, and its capital, Pristina, is a city under massive construction. Coming here feels like returning to China because there are construction sites everywhere. One can imagine that if visiting Pristina again in a few years, the streetscape will be very different.

Albanian flags fly everywhere in Pristina, almost more than Kosovo’s own national flag. There are also quite a few American flags, showing the strong influence of Albania and the United States on Kosovo.

Pristina is a multicultural city with a large number of mosques, Catholic churches, and Orthodox churches, which is also related to the diverse beliefs of the Albanians.

Albanians and Serbs

Starting with the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Montenegro became independent one after another, and Serbia recognized their statehood, with the sole exception of Kosovo. This is because the other independent countries were republics within Yugoslavia, whereas Kosovo had always been two provinces of Serbia (Kosovo and Metohija). In fact, similar to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the independence of the three Baltic states, the three Transcaucasian states, the five Central Asian “stans”, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova was not strongly blocked by Russia. Only the independence of Chechnya has been met with Russian military strikes to this day.

The deeper reason for Kosovo’s independence is actually an ethnic issue. In the Western Balkans, several major ethnic groups have had grievances for centuries: Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Albanians, and Macedonians. Among these major ethnic groups, all except the Albanians are Slavs with similar languages. Among them, Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks speak almost the same language but are divided into different ethnic groups due to different faiths. Serbs are Orthodox, Croats are Catholic, and Bosniaks are Muslim. In fact, before the breakup of Yugoslavia, these languages were collectively called Serbo-Croatian, while after the breakup, they were divided into Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin. Linguists from different countries have different views on Serbo-Croatian; some believe it is a community of different Yugoslav dialects, while others believe it is a political product of Pan-Yugoslavism, forcing different languages together. Interestingly, among the different language versions of Wikipedia, there are Serbian Wikipedia, Croatian Wikipedia, Bosnian Wikipedia, and Serbo-Croatian Wikipedia. Although understanding one allows you to understand the others, the political stance of many entries is diametrically opposite. For example, regarding the Bosnian War, the viewpoints of Wikipedia in different languages favor their own ethnicity, with only the Serbo-Croatian Wikipedia remaining relatively neutral.

The Macedonians are also Orthodox, but their language is actually the same as Bulgarian and is somewhat distant from Serbian. The faith of the Albanians is more complex, with followers of various religions, but their Albanian ethnic identity ranks higher than their religious identity.

Which ethnic group has lived in Kosovo “since ancient times” is a matter of varied opinions, with each group having its own version, but the core aim is always to favor their own group. However, before Kosovo’s independence, the Albanian population (Abbreviated as Albanians) already accounted for nearly 90%, while the Serbian population (Abbreviated as Serbs) was less than 8% and mainly concentrated in the northern region. Kosovo Albanians are mostly Muslims, which intensified the conflict with the Orthodox Serbs. Because of the Kosovo issue, friction often occurs between Albania and Serbia. Albania accuses Serbia of discriminating against and oppressing Albanians in Kosovo, while Serbia says Albania advocates separatism, harbors evil intentions, and attempts to rebuild “Greater Albania”.

When I took the bus from Serbia to Kosovo, the final stop was Gračanica, located 10 kilometers south of Kosovo’s capital, Pristina. Gračanica is a Serb enclave; the streets are full of flying Serbian flags, and there is a World Heritage monastery (Monastery Gračanica). The situation was quite good when I went, but just two years ago, there were Serbian troops protecting this place. When I took a taxi from Gračanica back to Pristina, I met a Kosovo police officer who was Serbian. When she learned that I came from Serbia and specially came to see the Gračanica Monastery, she happily said that I made the right choice. I tentatively asked her if Kosovo is part of Serbia. She said, “Regrettably, no, but we very much hope it is.” I don’t know if the “we” she referred to meant the Serbs in Kosovo, or if she hoped all Kosovars would be willing to join Serbia.

A completely different experience occurred when I was at the Ethnographic Museum in Pristina. Since there were few visitors, the guide was very enthusiastic to explain things to me for free, and after the tour, he asked me to sit down and chat. As an Albanian, he righteously complained to me about the atrocities of the Serbs during the Kosovo War. He told me that surviving the war was not easy for him. He was very gratified by Kosovo’s independence today because, he said, before independence, Serbia had always adopted policies of discrimination and assimilation against Albanians in Kosovo. For example, there used to be no schools teaching in Albanian; students were forced to learn Serbian, and only private schools taught Albanian, which were suppressed by the government. When I told him I had been to many places in Albania, he was overjoyed, as if Albania were his motherland. Kosovo Albanians also have a special affection for the United States; there is even a statue of Bill Clinton on the main street of the city center, and a replica of the Statue of Liberty nearby. I asked the guide why this was so, and he told me that the United States is the liberator of Kosovo and the savior of the Kosovo people. If the United States hadn’t bombed Serbia, Kosovo would not be independent to this day, just like the Chechen Republic in Russia (thinking about it, the US only dares to condemn Russia, but dare not bomb it like Serbia).

Entering Kosovo

The following is technical content.

Kosovo has three (or four) land neighbors: Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia, and Serbia. The entry regulations differ depending on the direction from which you enter or leave Kosovo. As a foreigner, you must be careful; otherwise, you might inadvertently get fined, repatriated, deported, or even permanently banned from entering by Serbia or Kosovo. First of all, Kosovo does not have embassies in many countries, so applying for a visa solely for Kosovo is quite troublesome. Fortunately, Kosovo offers 15 days of visa-free entry to holders of multiple-entry Schengen visas or residence permits from Schengen countries. I believe most people holding Chinese passports visit Kosovo this way.

Direct Entry

Kosovo’s complex entry policy is worth mentioning. To go to Kosovo, you either take a plane or enter by land (as a landlocked country, there is no sea route). Kosovo’s capital, Pristina, has an airport with quite a few flights to various parts of Europe, and there are routes from low-cost airlines like easyJet, so flying is a simple and feasible way. If entering by land, Montenegro, Albania, and Macedonia all recognize Kosovo’s independence, so entering and leaving Kosovo from these three directions poses no problem, just like flying. The most common mode of transport in Balkan countries is the bus, but there are also trains. There are trains running daily between Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and Pristina.

Entering Kosovo via these methods involves passing through Kosovo’s border controls. The only issue to note is that you must depart using these same methods; you cannot go directly to Serbia. Furthermore, if you go to Serbia proper later, you might be fined (low probability) or denied entry (very low probability). This is because, according to Serbian law, “Kosovo is an inseparable part of Serbia,” and entering the “Province of Kosovo” from a border crossing controlled by Kosovo is considered illegal entry into Serbia. Why is being fined a low probability event? Because the Kosovo entry stamp in the passport might not be noticed by Serbian border officials, especially if there are many stamps in the passport. Moreover, when entering Kosovo, you can ask not to have your passport stamped. If the border official agrees, then Serbia will not know you have been to Kosovo. Whether it is stamped or not doesn’t matter much because even without a stamp, your passport is registered in their computer system, which will be checked upon exit.

Entering from Serbia

If entering from Serbia, you must pass through the correct checkpoints (crossings). Northern Kosovo is effectively controlled by Serbia and is considered by Serbia to be part of its territory, with no checkpoints in between. As long as you are not self-driving, you won’t take the wrong checkpoint. Also, since Serbia does not recognize Kosovo, it does not consider there to be “borders” and “crossings,” only checkpoints. If taking a bus, you will generally enter through three checkpoints: Merdare, the Ibar River, and Mucibaba. I took a bus from Niš in southeastern Serbia, entered Kosovo through the Merdare checkpoint, left from Pristina, and returned to Novi Pazar in Serbia by bus via the Ibar River checkpoint.

It is worth noting that if you enter Kosovo from Serbia, you must return to Serbia. If you enter Kosovo and then leave via another crossing or by plane, Kosovo border officials will not stop you, but don’t think about going to Serbia again later. Again, this is because “Kosovo is an inseparable part of Serbia.” Leaving from a crossing controlled by Kosovo is considered illegal departure. Serbian border control has no record of it, meaning Serbia only has your entry record but no exit record; they don’t know if you left or overstayed. In short, enter from Serbia, exit to Serbia; if you don’t enter from Serbia, you cannot exit to Serbia. Entering Kosovo from Serbia and returning to Serbia is the only completely legal way of entry (complying with both Serbian and Kosovo laws).

Entering from North Kosovo

In addition to the above two methods, there is an unconventional way to enter Kosovo, which will not leave any Kosovo entry record. Northern Kosovo remains partially under Serbian control to this day, known as North Kosovo (Severno Kosovo). North Kosovo is a part of the Serb-controlled area that refused to separate when Kosovo declared independence in 2008. It is still controlled by Serbia, so there are no checkpoints between North Kosovo and the rest of Serbia. The capital of North Kosovo is Mitrovica. The Ibar River flows through the center of this city, but the north and south banks are controlled by Albanians and Serbs respectively, making it a frontline of confrontation and conflict. There are three bridges over the Ibar River, the most famous being the New Ibar Bridge located right in the center of the city. Although many conflicts have occurred on this bridge in the past, it is currently safe, and tourists can cross freely to the other side. There are no checkpoints on the bridge, nor is there any border control between Serbia and northern Mitrovica, meaning one can come to Kosovo from Serbia without hindrance. Entering Kosovo this way is also legal from Serbia’s perspective, but since you do not pass through a Kosovo checkpoint, there is no record in the Kosovo immigration system. Therefore, if you want to leave from other Kosovo ports, you may face obstacles, so to be safe, you should return to Serbia. If traveling in the opposite direction (from Kosovo to Serbia), you will encounter problems exiting Serbia.

There is a train from Kraljevo in Serbia to Zvečan in northern Mitrovica. This train used to go to Mitrovica and ultimately reach Kosovo Polje near Pristina, but since Kosovo’s independence in 2008, it only runs as far as Zvečan.

Other Destinations

This time, I only went to Pristina and the surrounding Gračanica Monastery in Kosovo, and I didn’t even stay overnight. There are other places in Kosovo worth visiting, worthy of another trip to explore. First is the ancient city of Prizren in southwestern Kosovo, which was once the capital of the Kingdom of Serbia. Secondly, the northern city of Mitrovica is controlled separately by Albanians and Serbs; crossing the Ibar River bridge is definitely a unique experience. The western city of Peja (Peć), near Montenegro, has World Heritage monasteries and Ottoman Turkish relics. To savor Kosovo in detail, I can only come back next time.

Last modified on 2017-03-16