Suddenly, I realized I have already been living in Japan for two years. During these two years, I have visited all forty-seven prefectures of Japan, yet surprisingly, I haven’t published a single travelogue about Japan (except for these four years at Google). Although I recorded many drafts during various trips, organizing this data into articles readable by others is no easy task. Fortunately, I recently developed BYVTrips, and my personal itinerary map is now public.

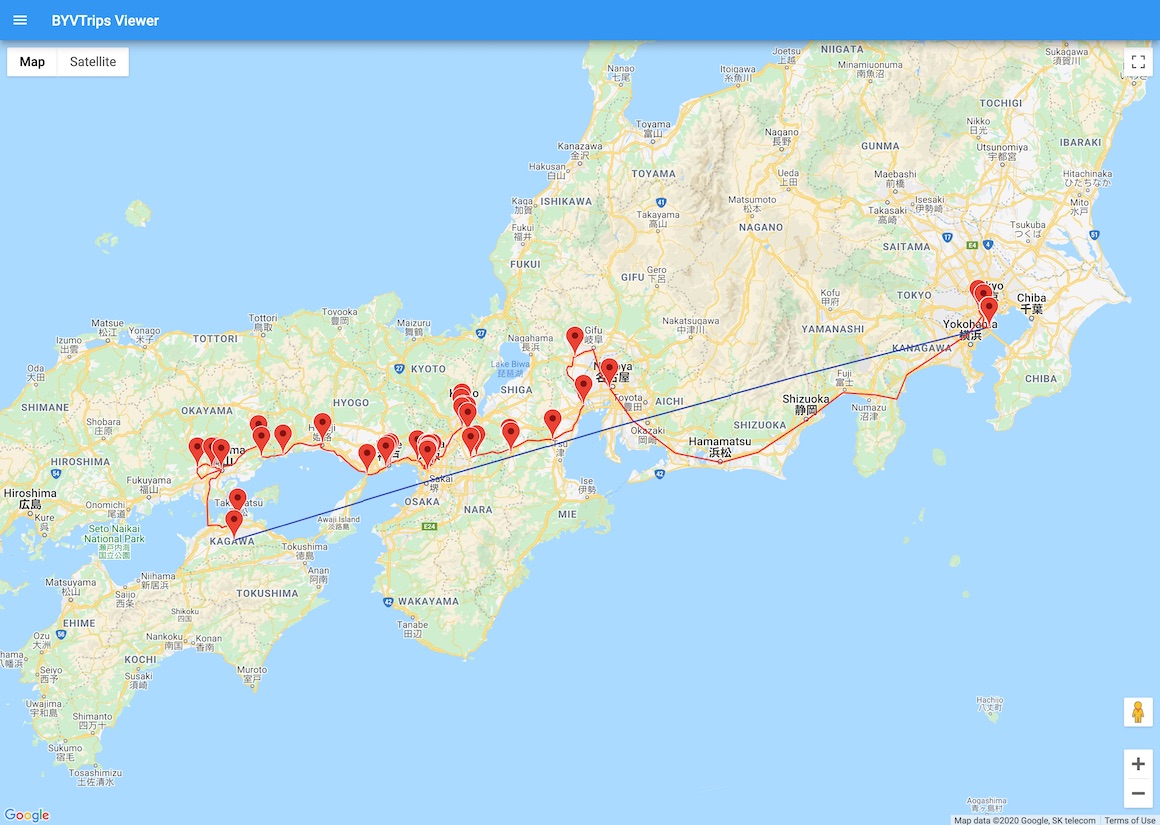

This trip took place in February 2020, before the coronavirus outbreak in Japan. My itinerary started in Takamatsu, followed the Seto Inland Sea to Osaka, then a half-day stay in Kyoto, traversing the Kii Peninsula, and finally returning to Tokyo from Nagoya.

Day 1: Takamatsu, Okayama, and Kibi Province

Departing from Haneda Airport, I arrived at Takamatsu Airport after an hour’s flight. This wasn’t my first time at Takamatsu Airport, although my destination wasn’t Takamatsu itself. Japan Airlines has ample ticket availability for Shikoku destinations—perhaps even an overcapacity—so it was easy to redeem tickets using British Airways Avios.

I took the airport bus to Takamatsu city center. Without lingering, I took a train directly across the Seto Inland Sea to Okayama via the “Honshi-Bisan Line” (commonly known as the Seto-Ohashi Line). As the name suggests, the Honshi-Bisan Line connects Honshu and Shikoku, linking the ancient provinces of Kibi and Sanuki. According to public annual financial statements, the Honshi-Bisan Line (along with a part of the Yosan Line) is the only railway line of the Shikoku Railway Company (JR Shikoku) that barely manages to turn a profit. All other lines operate at a loss, surviving on subsidies, and might face closure in a few years. Although the heavily indebted Japanese National Railways (JNR) was privatized and split up at the end of the Showa era, it could not reverse the difficulties in local railway operations caused by population decline. Japan has a large number of such unprofitable lines that continue to operate through subsidies. This may be partly due to the “sense of social responsibility” for sustainable operation held by Japanese companies, and partly due to heavy policy barriers against closing lines. In fact, many railway lines in Japan are now suspending operations indefinitely following “opportunities” presented by natural disasters, until the fact of their closure is eventually accepted.

After arriving at Okayama Station, I transferred to the Kibi Line to visit “Kibitsu Shrine,” the Ichinomiya (highest-ranking shrine) of Bitchu Province. A distinctive feature of this shrine is its very long wooden corridor, and legend has it that this shrine is the prototype for the one in the Momotaro story. Outside the shrine stands a statue of Inukai Tsuyoshi, who served as Prime Minister in the early Showa period. Because he opposed the Army’s expansion in Manchukuo, he was assassinated less than a year after taking office. His murder signaled the end of Taisho Democracy and the beginning of the comprehensive seizure of power by Japanese militarism.

Kibitsu Shrine was the chief guardian shrine of the Kibi Province. In the Asuka period, Kibi was divided into three provinces: Bizen, Bitchu, and Bingo. This location became Bitchu Province. The Ichinomiya of Bingo Province is also called Kibitsu Shrine and is located near Fukuyama. The Ichinomiya of Bizen Province, “Kibitsuhiko Shrine,” happened to be nearby, so I walked thirty minutes to get there. It is quite rare for the Ichinomiya of two Ritsuryo provinces to be so close together. Kibi is a region with a very long history; local powers can be traced back to the Kofun period after the 3rd century AD. During the Kofun period, seven regional powers emerged in the Japanese archipelago: Tsukushi, Hyuga, Izumo, Kibi, Yamato, Owari, and Kenu. I shall call them the “Seven Kingdoms of Wa”. These powers fought amongst themselves until the Asuka period, when power gradually concentrated in the Yamato Kingship. The Seven Kingdoms of Wa somewhat resemble the Seven Warring States in China and the Heptarchy in England—small states with similar cultures that, despite constant internal conflict, would unite against external enemies (Emishi, Silla). Japan’s recorded history roughly originates from this era; the preceding “Yamatai” and “Kuna” are semi-mythical histories with vague details, mostly recorded in Chinese historical texts. From the names of these small states, one can see that the characters used in Chinese historical texts for naming “barbarian lands” carry completely different connotations compared to those in Japanese historical texts (e.g., “Kuna” [Dog Slave] vs. “Hyuga” [Sun Facing]). At the same time, the Japanese disdain for the “Emishi” [Shrimp Barbarians] is also palpable.

After visiting the two shrines, it was getting late, so I had to return. Nearby is the Bitchu Kokubunji from the Nara period, which I left as a reason to visit again. I stayed near Okayama Station for the night.

Day 2: Well-field System, 47 Ronin, and Kobe Port Opening

I got up early the next morning, hurriedly ate some breakfast, and took a train along the Sanyo Main Line to Yoshinaga, then transferred to a bus to the Old Shizutani School. Although ostensibly a locally operated bus, it was actually just a seven-seater car with only two or three people on board who seemed very familiar with the driver—likely locals. Unless engaging in deep travel, foreign tourists probably wouldn’t come to a place like this as I did. Shizutani School was founded in the Edo period in 1670 and claims to be the “world’s oldest school for commoners.” The school taught Confucianism and houses a Confucius Temple. In modern times, it was converted into an elementary school, used until it became a Special Historic Site in the Showa era. The elementary school building is open for tours and serves as a data exhibition hall.

After viewing Shizutani School, I took the same small bus to Iri Station on the Ako Line. Even such small buses in the Japanese countryside operate strictly according to the timetable and are very reliable. While waiting for the train, I took a walk nearby and discovered a “Well-field” (Jingtian) monument. According to the information board, this was the site of an experiment with the Well-field system described in the Spring and Autumn Guliang Zhuan. Both this Well-field site and the Shizutani School were established by the same Lord of Okayama, Ikeda Mitsumasa, showing the depth of his Confucian scholarship.

The train finally arrived, and a few minutes later, I was at Banshu-Ako Station. Ako was a highlight of this trip for me; I came to pay respects to the famous “47 Ronin” (Akō Rōshi). I first learned of this story when reading The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, and later, reading Zhang Chengzhi’s book Respect and Farewell deepened my impression of it and my understanding of Japanese-style “loyalty”. The story essentially involves forty-seven samurai who, sparing no sacrifice—abandoning wives and children—avenged their wrongly accused lord. The plot is extremely fierce, and the ending tragic and heroic. In Tokyo, I have visited Sengaku-ji to see the graves of the 47 Ronin. Every time I go to Sengaku-ji, I see people specifically coming to burn incense at the graves of the loyal samurai. The story comes from the Ako Domain, and this time I could explore the source. As the fief of the 47 Ronin’s lord, reverence for the loyal samurai is visible everywhere in Ako. The Japanese respect for the 47 Ronin is comparable to the Chinese admiration for Jing Ke. There are three main sights in Ako: Kagakuji Temple, Oishi Shrine, and Ako Castle. Kagakuji and Oishi Shrine house relics and statues of the 47 Ronin, as well as handwriting by the “God of the Navy,” Togo Heihachiro, praising them. Not much remains of Ako Castle, but there is a tenshudai (donjon base) inside the castle grounds offering a view from a height. Afterwards, I went to the Ako City Museum of History, which features not only the 47 Ronin but also introduces Ako’s traditional salt industry.

Leaving Ako, I continued east by train to Himeji. I had visited Himeji Castle over three years ago, so here I simply transferred to the Sanyo Electric Railway, which I hadn’t ridden before. More than half an hour later, I arrived at Maiko-koen Station, right directly under the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge. It was already past 4:00 PM, and with little time left, I headed straight to the seaside to admire the spectacular view of the bridge. There is a western-style building by the sea called “Ijoukaku,” which is the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. Sun Yat-sen stayed there during his time in Japan, and the museum introduces his life, especially his experiences in Japan. The owner of the villa was Wu Jintang, the wealthiest overseas Chinese merchant in Kobe. Several exhibition halls on the second floor introduce his life and experiences. After making his fortune in Japan, Wu Jintang continuously supported Sun Yat-sen’s revolution while also being enthusiastic about Japanese philanthropy. In his later years, his soul returned to his hometown, and he was buried in Cixi, though regrettably, his tomb was severely damaged during the Cultural Revolution.

I stayed until the museum closed. I watched the twilight by the sea for a bit before continuing to Kobe. The sunset scenery by the sea was truly beautiful, so beautiful it felt unreal. I originally planned to visit the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake Memorial, but I arrived just before 18:00. Although it closes at 19:00 with last entry at 18:00, the front desk staff, eager to get off work, refused entry claiming that her clock had already passed the time. So, I turned to the Kobe City Museum, which closes at 21:00. The museum had a temporary exhibition on “Takenaka Corporation’s Architecture”. Takenaka Corporation has a long history, founded four hundred years ago starting with the construction of Buddhist temples. The historical buildings exhibited were exquisite; I couldn’t help but exclaim that this is true craftsmanship. The first floor of the museum houses a permanent exhibition on Kobe’s history, covering everything from ancient times to the opening of Kobe Port and the present day. The model of the streets in the former Foreign Settlement is particularly worth seeing.

By the time I finished viewing, it was already 9:00 PM. Generally speaking, it is difficult to sightsee until this hour in Japan because most places close early. This tradition was noted by missionaries visiting Japan before the 18th century, who mentioned that Japanese people went to bed and woke up earlier than Chinese and other Asians. Although now, in big cities like Tokyo, this has been replaced by a new culture of overtime work. I walked to Sannomiya Station, took the Hanshin Line for 40 minutes, and stayed the night in Amagasaki.

Day 3: Tatsuno Kingo’s Osaka and Heian Period Toji

Despite the early start and late finish the previous day, I woke up very early again this morning. Having something to look forward to makes getting out of bed easy. After a simple breakfast, I went to Amagasaki Castle. This Japanese castle had long been burned down; the newly built tenshukaku (keep) was completed only in 2018, making it possibly the “newest” castle in Japan. Afterward, I went to the nearby Amagasaki Shinkin Bank Hall, which houses two museums that are free to visit. One unique museum is the “World Moneybox Museum,” which collects piggy banks from all over the world. The other was a special exhibition by a local artist. I viewed a paper-cutting exhibition, and the artist himself was incredibly surprised that a foreigner like me was there; he insisted on giving me one of his works and taking a photo together. On the way back to Hanshin Amagasaki Station, I passed Honkoji Temple. This temple is the head temple of the Honmon Line of the Hokke Shu (a branch of Nichiren Buddhism). Although unassuming and visited by few, it has deep culture and a long history. I can’t help but marvel that Japan is truly a cultural treasure trove of East Asia; both the density and depth are astounding. This layering can even be seen in the Japanese language itself.

Afterward, I took a train around Osaka to see the scenery and arrived at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, on Nakanoshima. They generally exhibit modern art here, which I don’t particularly like, but I paid to go in because there was a special exhibition on “Impossible Architecture.” After viewing it, I went to the nearby Osaka City Central Public Hall, a masterpiece by Tatsuno Kingo. Unfortunately, there were events in the various halls inside, so I could only admire it from the outside. To the west, I also saw the Osaka Library, City Hall, and the Old Building of the Bank of Japan Osaka Branch, a collection of the finest Meiji and Taisho era architecture. Sadly, this aesthetic came to an abrupt halt after World War II, ending along with the era of European empires. Thereafter, the whole world was cleansed by “Modernist architecture.”

Continuing on, I took the Keihan Electric Railway to Chushojima near Kyoto to visit the attraction Gekkeikan Okura. Gekkeikan is a famous Japanese sake, and the museum introduces brewing techniques. Nearby is a small temple, Tokosan Chokenji, belonging to the Daigo school of Shingon Buddhism. Inside the temple is a Goma altar for performing important esoteric Buddhist rituals. There were traces of burning on the ground, as if it had just been used. Walking through a shopping street, I reached Momoyamagoryo-mae Station on the Kintetsu Railway and rushed to Toji Temple in Kyoto, entering just before the gates closed.

Toji, even amidst the forest of temples in Kyoto, can be said to be unique; it is the only surviving structure from Heian-kyo. Toji sits on the east side of the central axis of Suzaku Avenue in front of Rashomon Gate in Heian-kyo, symmetrical to Saiji (West Temple). Inside the temple, the Kondo (Main Hall) and Kodo (Lecture Hall) enshrine the Medicine Buddha (Yakushi Nyorai) and Vairocana Buddha (Dainichi Nyorai) respectively. In the southeast corner stands the Five-Story Pagoda. From this layout, one can see that the temple layout of that era had already transitioned from “centered on the pagoda” to “centered on the Buddha hall.”

Emperor Saga gave Toji to Kukai, the founder of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, marking the beginning of the Shingon sect. Today, Toji remains the head temple of Toji Shingon, a major branch of Esoteric Shingon Buddhism, serving as a collateral branch to Koyasan Shingon. Compared to the Zen and Pure Land sects, which have broader followings in Japan, Shingon is more conservative and archaic. For example, the first two sentences of the Buddhist scripture Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī (Great Compassion Mantra):

南無喝囉怛那哆羅夜耶。南無阿唎耶。婆盧羯帝爍鉗囉耶。

Soto Sect (Zen) pronunciation:

なむからたんのーとらやーやー。なむおりやーぼりょきーちーしふらーやー。

Namu karatannō. Torayāyā. Namu oriyā. Boryokīchī. Shifurāyā.

Shingon Sect (Esoteric) pronunciation:

のうぼう。あらたんのうたらやあや。のうぼありや。ばろきてい。じんばらや。

Nōbō. Aratannō tarayāya. Nōbo ariya. Barokitei. Jinbaraya.

Sanskrit:

Namo ratna trayāya | namo āryĀvalokiteśvarāya

From the transliterations above, it can be seen that the Shingon pronunciation retains more features of Tang Dynasty Middle Chinese, such as voiced consonants and back-high vowels, whereas the Soto Sect’s phonology leans more towards the Song Dynasty and later. Although the discrepancy between spoken and written Japanese and its complex historical layers make learning difficult, these are precisely the aspects that fascinate me.

Here is my own translation:

Homage to the Three Jewels! Homage to the Noble Avalokitesvara (Bodhisattva)!

Although this verse is short, it contains many interesting cognates. “Namo” means to bow or pay homage, cognate with the common modern Indian greeting “namaste”. “Ratna” means jewel; Ratna is also an Indian female name—I have a friend named Ratna. “Trayāya” means three, a cognate with the English word “three”. “Ratna trayāya” means “Three Jewels,” referring to the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. “Ārya” means noble or holy, a cognate with “Aryan”. “Āvalokiteśvarā” means One Who Perceives the Sounds of the World (Guanyin).

As dusk approached, I didn’t have enough time at Toji, so I can only visit the treasure hall next time. Leaving after 5 PM, considering that most attractions in Japan are closed by then, I prepared to go straight to dinner.

To ride some lines I hadn’t taken before, I first took a Kyoto bus, crowded at any time, to Karasuma Shijo, then walked to Karasuma Oike. I took the subway Tozai Line to the terminus, Rokujizo, then transferred to a JR West train to Uji. I stayed the night in Uji.

Day 4: Iga Ninja and Josiah Conder

I woke up early again in the morning. I originally planned to go to Byodoin. I had been to Byodoin before, but the reason for returning was that I missed the Phoenix Hall last time due to the long lines. Later, after seeing the replica of the entire Byodoin in Hawaii, I felt deep regret. I arrived at the gate of Byodoin before 8:30 AM, but unfortunately, although Byodoin opens then, the Phoenix Hall doesn’t open until 9:30 AM. Not wanting to wait another hour, I had to accept the regret again, leaving a reason to return in the future.

After changing plans, I decided to immediately take the Kansai Main Line to Iga. The Kansai Main Line requires a transfer at Kamo. Continuing east, the eight-car train turned into a two-car one-man operated train, highlighting the drastic drop in population density. Soon, I arrived at Iga-Ueno, transferred to the Iga Railway (formerly part of Kintetsu), and arrived at Uenoshi Station in 7 minutes.

The main purpose of coming to Iga was to see Ueno Castle, one of Japan’s famous castles. Built before the 16th century, the donjon was later destroyed and rebuilt in 1935. Climbing the donjon offers a panoramic view of the surroundings. Ueno Castle has extremely high stone walls; looking down at the moat from above is like staring into an abyss. The stone walls of Ueno Castle and Osaka Castle are tied for the highest in Japan.

Walking north of Ueno Castle, I found the “Iga-ryu Ninja Museum.” Actually, my interest in ninjas is average, but I watched a ninja show here anyway. The performers used various weapons and props and threw shuriken, showing some real skill. Another attraction is the ninja house, filled with various traps and even secret escape passages. Although not as magical as in manga and novels, the mechanisms were ingenious. As a symbol of Japanese culture, ninjas became extremely popular in the West starting in the 1980s, representing mysterious Eastern martial arts alongside Chinese Kung Fu. In my two years in Japan, this was my first contact with ninja culture. Besides the Iga school, there is also the Koga school; I hope to visit Koga if I have the chance.

Leaving Iga, I returned to the Kansai Main Line and continued forward, riding all the way to Kuwana City, which is already within the Greater Nagoya area. I had passed through Kuwana before, visiting the “Nabana no Sato” amusement park, but I missed Rokkaen, so that was my main objective this time. Rokkaen is the mansion of the local tycoon Moroto Seiroku from the Taisho era. As a representative of the private residences of wealthy merchants in the Meiji and Taisho periods, Rokkaen combines Japanese and Western architectural styles, featuring interconnected Japanese and Western buildings. The total floor area is large, with a two-story Western-style building at the front and a Japanese-style building and garden at the back, both exquisitely designed. Rokkaen was designed by the British architect Josiah Conder, the “Father of Modern Japanese Architecture.” Conder’s name is thunderous in Japan; he designed the “Rokumeikan,” the most famous state guesthouse of modern Japan. He was also the teacher of Tatsuno Kingo, so he can be said to be the founder of Japanese Western-style architectural design. I lingered here for over an hour, exploring every corner.

Why has Japan been able to preserve relics from various historical eras so perfectly, like a mille-crepe cake? I have been trying to answer this question. Perhaps it is because, until the Pacific War, Japan had not been conquered by foreign enemies for a thousand years, nor did it suffer serious internal chaos, allowing society to maintain amazing stability for a long time. All this relied on its unique geographical environment, worthy of being called a fairyland on the sea. Japan’s precipitation and temperature are very suitable for agriculture, and abundant flora, fauna, and volcanic ash kept the land fertile for a long time. Before agriculture was introduced, only a few regions like Japan, Peru, and British Columbia formed large-scale sedentary hunter-gatherer civilizations. Abundant fishing and hunting resources made agriculture not even that advantageous, so much so that the agricultural Toraijin (settlers from the continent) replaced the hunter-gatherer Jomon people very late. “When the granaries are full, people follow the rules of conduct; when there is enough food and clothing, they know honor and shame.” As early as the Song Dynasty, a thousand years ago, Ouyang Xiu summarized Japan as having “fertile soil and good customs” (Song of the Japanese Sword); at that time, Japan was still in the Heian period. Inexhaustible timber resources allowed Japan to have a large number of structurally complex and massive wooden buildings. Before coming to Japan and seeing them with my own eyes, I didn’t even believe such pure wooden structures could be built, let alone stand for a thousand years. By comparison, the natural and geopolitical environments of mainland China and the Korean Peninsula really pale in comparison.

After seeing Rokkaen, I continued east, walking along the mouth of the Kiso River. On the way, I passed a place called “Shichiri-no-watashi” (Seven Ri Ferry), which was once a strategic point on the Tokaido road traveled by the Sankin-kotai processions of various domains during the Edo period. From here, one could take a boat for seven ri (about 27 km today) to reach Atsuta on the Tokaido, hence the name “Shichiri-no-watashi.” Then I walked to Kyuka Park, the site of the former Kuwana Castle. The main structure of Kuwana Castle no longer exists, but the moat has been preserved, becoming a scenic spot in the park.

Returning to Kuwana Station, I chose to detour via Ogaki to Nagoya to experience the Yoro Railway. I encountered some trouble entering the station because I didn’t know that the Yoro Railway doesn’t accept IC cards for entry and requires buying a ticket from a machine outside. Inside, there were still ticket machines, but I was blocked when changing platforms. Due to poor communication, I got on the train anyway, but the status of the transport card on my phone remained as “not exited.” Later, upon returning to Tokyo, I found I couldn’t enter stations. I found a staff member, but they said I could only resolve the card issue by returning to the Kansai area to find Kintetsu Railway.

Summary

This trip ends here. Although it was less than four days, I was able to traverse Sanyo and Kansai using Japan’s developed and convenient railways, enjoying the scenery and reading the mille-crepe-like Japanese culture. I have had dozens of such wandering journeys; I hope to have the time to write them all down one by one.

Last modified on 2020-04-14