Continued from Northern Immortal Islands Part 1.

Maritime Fuji: Rishiri

After having lunch on Rebun Island, I boarded the ferry to Rishiri.

Somewhat unexpectedly, there were no seats on the ship, only Washitsu (Japanese-style rooms). A Washitsu generally refers to a room with tatami mats, but sometimes thin carpets are also considered Washitsu. The rule for Washitsu is that you must take off your shoes before entering, and it is best to wear socks, otherwise it is considered uncouth. The floor of the Washitsu was very clean; everyone sat on the floor, and some people lay down to sleep. This style of cabin is becoming rare in Japan.

The ship sailed for less than an hour before arriving at Rishiri Island. Looking out at the sea ahead during the journey, I could see Rishiri Fuji gradually becoming clear. Mount Rishiri, at an altitude of 1,721 meters, is a perfect cone-shaped volcano, hence it is called Rishiri Fuji.

There were not many tourists on the island yet, and many hotels were still closed. However, the Hotel North (Hokugoku Grand Hotel), which I was lucky enough to book, had opened some countryside cottages at a price much cheaper than usual.

After dropping off my luggage, I set off towards Mount Rishiri. Of course, I didn’t plan to climb the mountain, but just intended to walk around the foot of the mountain, aiming only for the Kanrosensui (Sweet Dew Spring Water) at the 3rd station. There is a road from Rishirifuji Town, about 4 kilometers away with an elevation gain of 200 meters. I walked for over an hour, passing a campsite along the way.

At the campsite, I noticed that “portable toilets” were being sold and collected. Many places in Japan require climbers to bring their waste back down the mountain and forbid relieving oneself just anywhere on the mountain. I don’t know how strictly Japanese people adhere to this rule, but it’s really hard to imagine in other countries. Before entering the hiking trail, I also found a shoe washing station intended to prevent foreign seeds from being brought into the mountain.

After trekking for more than ten minutes from the campsite, I finally arrived at the Kanrosensui. The spring water gushed out from the rock wall, cold and clear, and the taste was indeed somewhat sweet. This Kanrosensui is also one of Japan’s “100 Famous Waters”.

Kanrosensui marks the 3rd station (Sangome) of Mount Rishiri (there are ten stations in total). Walking further would mean truly starting the mountain climb. If one wants to climb the mountain, they must set out very early in the morning to return the same day, so I turned back from here.

Returning to Rishirifuji Town, I passed an onsen (hot spring) facility. Having walked 8 kilometers round trip, I was a bit tired, so naturally, I wanted to bathe and rest. As part of daily life for Japanese people, the price of onsens is not expensive—only 500 yen—and most patrons are locals. There was an open-air bath with excellent scenery where one could enjoy the cool breeze and beauty of the forest.

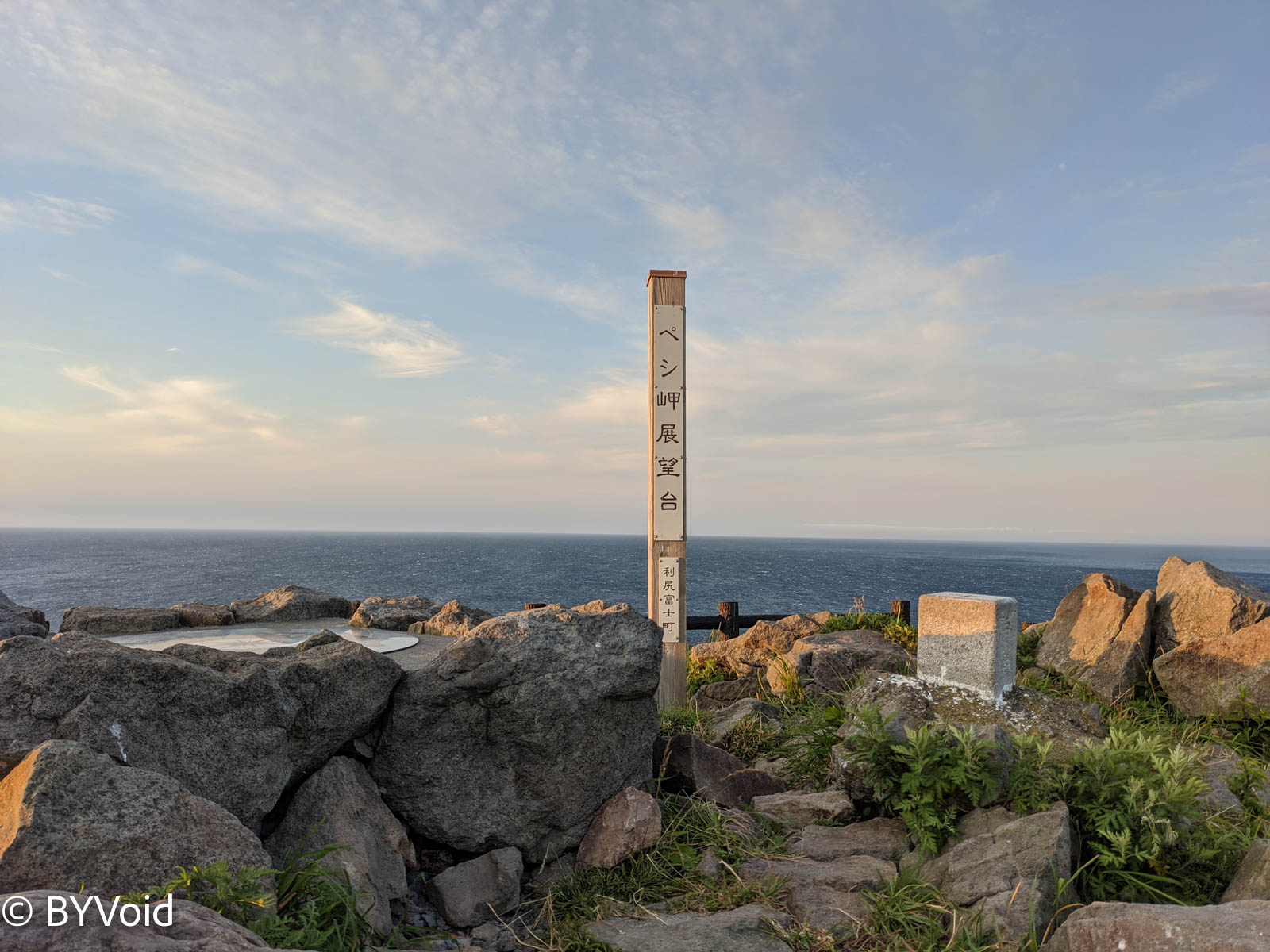

When I came out of the onsen, it was already evening. Before the sun set, I climbed Cape Peshi (Peshi-misaki). This name is obviously Ainu; otherwise, it wouldn’t start with a “p”. The climbing path up the cape was very steep and accompanied by strong winds. There is a small platform halfway up the mountain where grave markers of Aizu Domain samurai stand, commemorating the Aizu warriors stationed here during the Edo period.

In 1807, on the eve of Japan opening up to the world, Russia intended to send troops to Hokkaido to open Japan’s doors for trade using gunboats. At that time, the Edo Shogunate ordered the Aizu Domain to garrison the northern territories, so more than 200 retainers arrived on Rishiri Island. Although no actual conflict with Russia broke out, poor nutritional conditions and the bitter cold claimed many lives, and some of the survivors suffered shipwrecks on their way home. Russia ultimately failed to expand southward and surely could not have imagined that a hundred years later, facing a rising Japanese Empire, they would suffer a crushing defeat.

I struggled to climb to the top, where the view was unparalleled, but the wind was so strong I couldn’t stand up straight and could only crouch behind a rock to look.

After descending the mountain, the sun was about to set, and the afterglow made Rishiri Fuji look even more beautiful.

Waking up the next morning, the sunshine was exceptionally bright. The hotel delivered breakfast early in the morning, which was Japanese-style Kamameshi (kettle rice).

I set off after enjoying breakfast. The plan for the day was to rent a car and drive around the island. Renting a car on Rishiri Island is also expensive, but cheaper than Rebun, mainly because there are more competitors. The total price for a 5-hour rental with a drop-off at the airport was 9,500 yen. The car was a Kei car (light automobile) unique to Japan. This price is about twice as expensive as on the Hokkaido mainland.

Starting the drive, I first went to a small mountain pond called Himenuma (Princess Pond). The feature here is the ability to photograph the inverted reflection of Rishiri Fuji in the water, but the premise is that the sky must be particularly clear and the water still. Regrettably, I didn’t see the reflection, but walking around the lake was still refreshing.

The weather was sunny that day, and the seaside scenery was also very beautiful.

Although Rishiri Island is not large, there are two museums on the island, both introducing local natural history and folklore. I learned in these two museums that the colonization of Rebun and Rishiri began in the Meiji era, and the influx of population did not end until after World War II. Because this is the confluence of the Tsushima Warm Current and the Liman Cold Current, there are large fishing grounds nearby, attracting a large number of fishermen to catch fish here. Although the latitude of the two islands is high, the winter climate is relatively mild, making it very suitable for settlement. The population of Rishiri Island peaked at 11,234 after WWII (Source), and has been declining since, with less than 3,000 people in 2020. Until the 1990s, there was even a ferry from Otaru connecting Rishiri and Rebun.

Although Rishiri and Rebun are not far apart, their climates and vegetation are significantly different. Rishiri’s vegetation is dominated by trees, while Rebun is basically grassland. This is also caused by ocean currents; the warm current is stronger around Rishiri, while the cold current is stronger around Rebun.

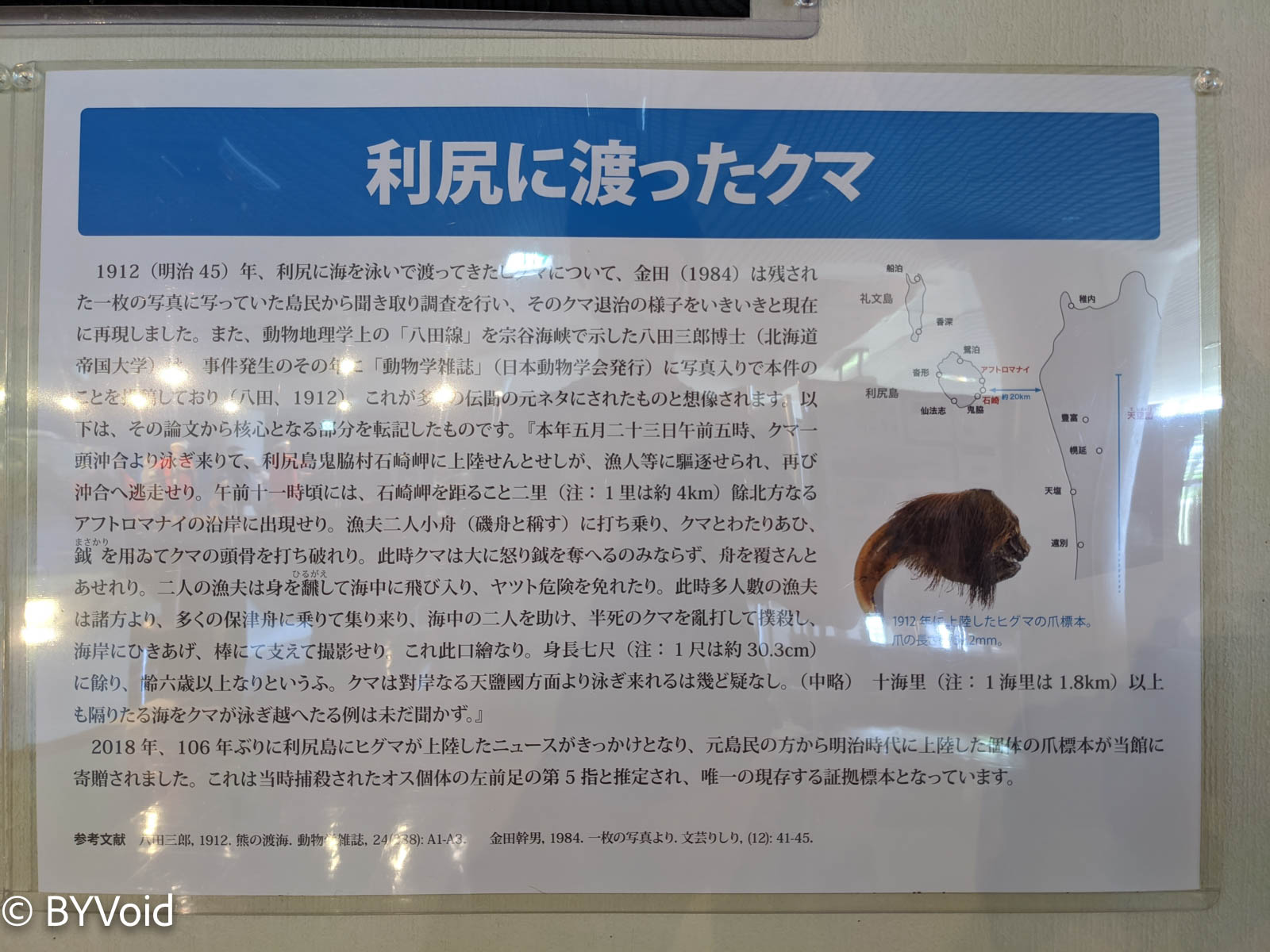

On the Hokkaido mainland, one often sees signs warning “Beware of Bears”. Although there are no bears on Rishiri Island, there have been multiple instances of bears crossing the sea to get there. Despite Rishiri being separated from Hokkaido by at least 20 kilometers of ocean, bears can actually swim across!

Both Rishiri and Rebun come from the Ainu language, meaning “High Island” and “Island on the opposite side of the sea”. Many place names in Hokkaido come from the Ainu language, especially the many words starting with the “ra” (ら) row, which indicates they are not Wago (native Japanese words). A common feature of Japanese and Korean is that the liquid sounds /l/ and /r/ cannot be the beginning of a word. So, if you see a Japanese word starting with the “ra” row, you can almost judge that it is not Wago. South Korean goes a step further, where even the consonants of all Sino-Korean words starting with /l/ are dropped (North Korea does not drop them). Japanese has a similar phenomenon appearing in individual Wago-ized words, such as “sulfur” being read as “iou” (instead of riou). The L sound holds a certain exotic appeal in the minds of Japanese people; legend has it that the brand Lululemon was named specifically to create a “foreign feel” for the Japanese.

At noon, I arrived at Kutsugata Port in the southwest of Rishiri Island, where I had lunch and bought the most famous local specialty, Rishiri Kelp (Konbu). Sea urchin (Uni) is also a famous local specialty; it is considered a delicacy in Japan and is expensive. Interestingly, when the Japanese first colonized Rishiri a hundred years ago and cultivated kelp here, they treated sea urchins as a pest that destroyed kelp and removed them on a large scale.

Finally, I returned to Rishiri Airport, completing the loop around the island. On this small island, the scenery of Rishiri Airport can be described as open, because you can take in the entire view of Rishiri Fuji behind the runway. I was taking an All Nippon Airways (ANA) flight from Rishiri to Sapporo New Chitose. I saw a Boeing 737 parked on the runway, which is only 1,800 meters long. While waiting in the lobby, I also noticed several pilots taking photos together on the runway; it seems that not everyone gets to fly this route.

The takeoff process was very special and a bit thrilling. Before boarding the plane, I felt a very strong crosswind, making it difficult even to walk. Unlike standard takeoff procedures, the engines of this Boeing 737 were revved up before the taxi/takeoff roll began. The plane initially remained motionless while the engines spun furiously, creating a huge noise, and the entire airframe vibrated violently. Immediately afterward, the plane suddenly accelerated and lifted off the ground within a few seconds. After takeoff, the climb rate was very fast, followed by a sharp turn in the air. It seems that taking off and landing at this airport with a short runway, complex terrain, frequent fog, and severe crosswinds is really not an easy task. The plane was less than 30% full; I wonder why ANA uses a Boeing 737. Could it be for pilot training?

Not long after, I could overlook the panorama of Rishiri Island from the window.

Switzerland of Hokkaido: Lake Shikotsu and Lake Toya

After an hour, the plane landed smoothly at New Chitose Airport. Tonight, I would drive to Lake Shikotsu and Lake Toya.

Renting a car on the Hokkaido mainland is truly much cheaper; including insurance, it was less than 3,000 yen a day. Lake Shikotsu is only about a 30-minute drive from Chitose.

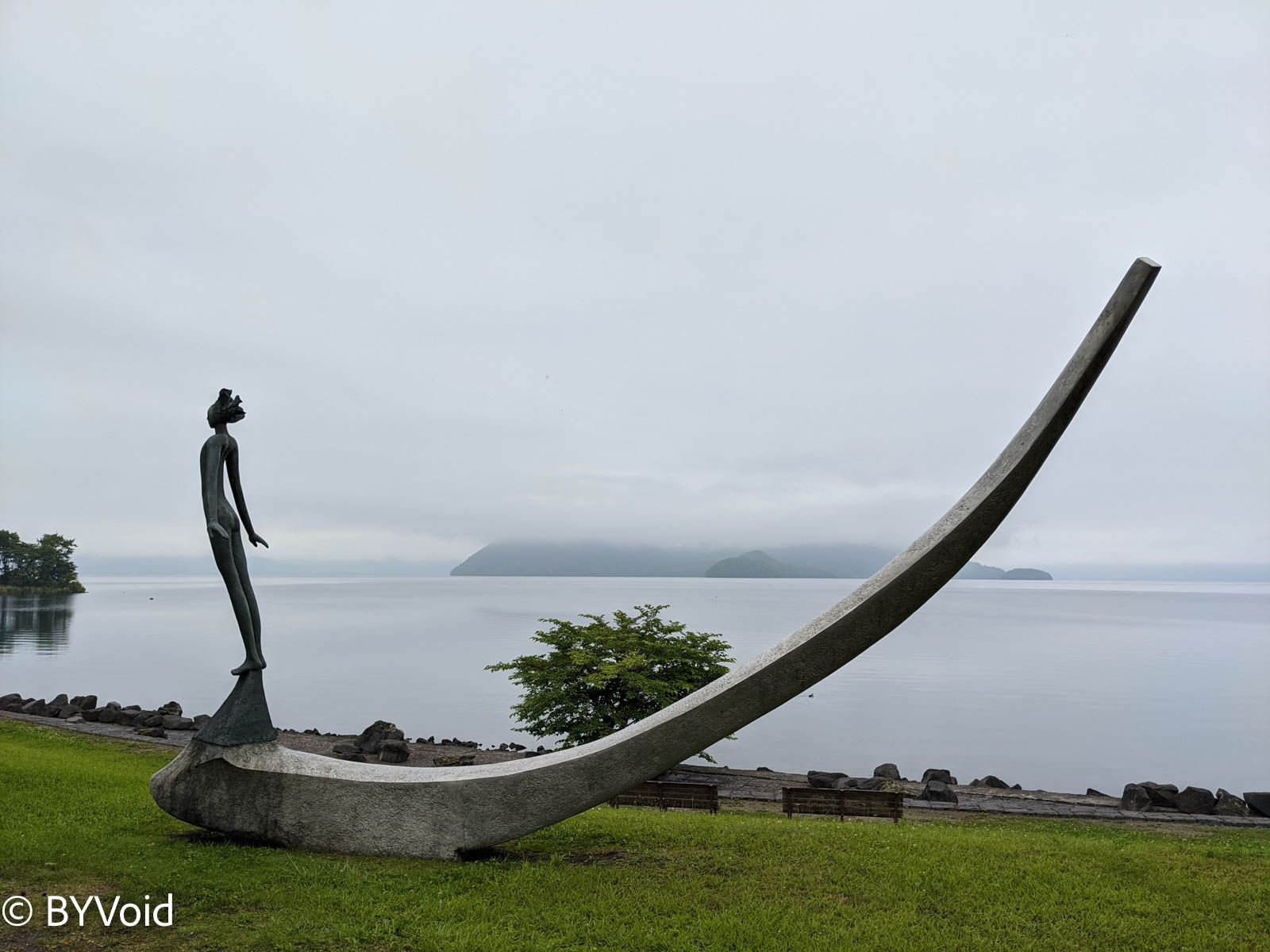

When I arrived at Lake Shikotsu, it was exactly the moment when the afternoon sun was most brilliant. The lakeside scenery was beautiful, and the water was crystal clear. Walking by the lake, I had a momentary illusion of being on the shores of Lake Geneva (Lac Léman) in Switzerland. There is a visitor center by the lake featuring exhibits on the nature of Lake Shikotsu, and next to it is a railway museum commemorating the Oji Paper railway. There are many onsen hotels around Lake Shikotsu, attracting a large number of vacationers.

Leaving Lake Shikotsu, I continued to Lake Toya, about an hour’s drive away. Lake Toya is more famous than Lake Shikotsu and usually has many tourists, especially tour groups. I arrived at the lakeside just before sunset. The clear lake water looked exceptionally bright under the setting sun, and in the distance, Mount Yotei was shrouded in the mist rising from the lake. Dinner was at a Western-style restaurant called Boyotei; this restaurant has exquisite decoration, an elegant environment, and is a century-old shop.

After dinner, the sun had already set, and there was twilight on the horizon. I returned to the lakeside to admire Lake Toya shrouded in the dusk.

That night I stayed at an onsen hotel called Yutorelo Toyako. Because it was a weekday, coupled with a promotion, the price was particularly cheap and included a hearty breakfast.

Near Lake Toya is an active volcano called Mount Usu. This volcano erupted in 2000, destroying some houses. After breakfast, I went to the ruins to investigate. However, I only saw a closure notice at the entrance because bears had recently been spotted inside.

People often sight bears in the mountains and forests of Japan, so many places have numerous signs warning “Beware of Bears”. Although bears generally do not actively attack humans, their destructive power is astonishing once provoked. Even with so many bears, news of people being killed by bears is rare, yet the cautious Japanese paste such warnings everywhere. Perhaps this helps people stay as far away from bears as possible; after all, facing humans, bears are the truly vulnerable party.

Hastily saying goodbye to Lake Toya, I drove back to New Chitose Airport along the expressway. It is about 120 kilometers from Toya to Chitose, taking less than an hour and a half to drive. The expressway toll was not cheap; even with ETC, it deducted 3,200 yen.

A Glimpse of Kyoto

The next leg of the journey was flying from New Chitose Airport to Osaka Itami Airport, with an expected stopover of 7 hours, before flying back to Tokyo Haneda. The reason for this route was that I used United Airlines miles to redeem an ANA ticket from Rishiri to Tokyo. Due to mileage ticket seat restrictions, I couldn’t fly directly from New Chitose to Tokyo Haneda. So, I decided to stay overnight at Lake Toya and take a quick look at Kyoto. In reality, there were not many people on the plane; ANA would really rather fly empty planes than release more mileage tickets.

The plane arrived at Osaka Itami Airport at noon. I took the Osaka Monorail to transfer to the Keihan Railway, going straight to Karasuma in downtown Kyoto, and then transferred to the subway to reach Keage Station. Next to Keage Station is the tunnel entrance of the Lake Biwa Canal. The Lake Biwa Canal is a Western-style canal engineering project that bored through the Higashiyama mountains to divert water from Lake Biwa to Kyoto. There is also a section of Roman-style elevated aqueduct called Suirokaku. Completed in 1890, the Lake Biwa Canal not only solved Kyoto’s drinking water problem but also utilized the height difference for power generation, as Lake Biwa’s altitude is higher than Kyoto’s ground level.

Near Keage Station, there is a remnant of an incline railway, which was once used to transport boats. Boats in Kyoto’s water network were lifted to Keage, entered the tunnel from here, and could sail directly to Lake Biwa. Now, this railway is a tourist attraction, with cherry blossoms blooming in spring.

Walking a short distance along the Suirokaku leads to Nanzen-ji; a part of the aqueduct even passes through the temple grounds. Nanzen-ji is one of the many great temples in Kyoto and is the head temple of the Nanzen-ji branch of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. This temple was built in the Kamakura period in 1291. At that time, China was under the rule of Kublai Khan of the Great Yuan Empire. After two failed expeditions to Japan, many Southern Song immigrants fled to Japan, bringing fresh blood to Japanese culture. Since Nanzen-ji was built at the behest of the Emperor, it ranks above the “Kyoto Gozan” (Five Mountains of Kyoto) of the Rinzai school, making it the highest temple of Japanese Zen Buddhism.

The main sights of Nanzen-ji are the Sanmon, the Hojo (Abbot’s Quarters), and Nanzen-in. The Sanmon, also known as the Mountain Gate, is a huge purely wooden structure with a multi-eaved Irimoya-zukuri (hip-and-gable) roof. You can climb up the Sanmon to overlook the entire Nanzen-ji.

Since the Japanese words for “three” (san) and “mountain” (san) are homophones, Sanmon is often confused with Mountain Gate. A Mountain Gate, as the name suggests, is the gate to enter the mountain and is generally the first gate of a temple. However, Sanmon is an abbreviation for “Three Vehicles Gate” or “Three Liberation Gates” (San-gedatsu-mon). “Three Vehicles Gate” refers to the three vehicles of Sravaka, Pratyekabuddha, and Bodhisattva, through which one can attain the status of Arhat, Pratyekabuddha, and the supreme enlightened Buddha respectively. The theory of “Three Liberation Gates” comes from the Yogacarabhumi Sastra of the Yogachara school of Mahayana Buddhism, referring to the “Empty Liberation Gate,” “Signless Liberation Gate,” and “Wishless Liberation Gate.”

The Nanzen-ji Hojo is the main residence of the head priest and contains several Karesansui (dry landscape) gardens. The most famous is its garden, and it is said that the scenery during the autumn foliage season is breathtakingly beautiful.

Unknowingly, I spent an afternoon at Nanzen-ji and didn’t come out until it closed at five o’clock. I didn’t have time to visit Tenju-an within the temple or the nearby Eikan-do (Zenrin-ji) of the Jodo school, so I’ll have to come back later. There is a Nanchan Temple (Nanzen-ji) of the same name in Mount Wutai, Shanxi, China. The main hall of that Nanchan Temple was built in the Tang Dynasty in 782 AD and is the oldest existing wooden structure in China. I hope to visit it in person one day.

After slowly touring Nanzen-ji, it was already evening. I was willing to make a special trip to Kyoto just to see Nanzen-ji, and there are dozens of such places around Kyoto. It is truly fortunate that Kyoto was not destroyed by war.

I returned to Osaka Airport in the evening and flew back to Tokyo, bringing this short but fulfilling itinerary to an end.

Last modified on 2021-08-14